| |

Defenses of Manila Bay |

|

|

Four islands protected the mouth of Manila Bay from attack. Corregidor,

the largest island, was fortified prior to World War I with powerful

coastal artillery and named Fort Mills. The tadpole shaped island lay

two miles from Bataan, and was only 3-1/2 miles long and 1-1/2 miles

across at its head. This wide area, known as Topside, contained most of

Fort Mills' 56 coastal artillery pieces and installations.

The next feature

proceeding east from Topside was Middle side, a small plateau containing

more battery positions and barracks. East from Middleside was

Bottomside, the low ground where a dock area and the civilian town of

San Jose was located. Further east was headquarters, hospital, and

communication tunnels contained within Malinta Hill. The narrow tail of

the island continued east, with a small landing strip, Kindley Field,

until ending among the rocky beaches of Hooker Point.

Fort Hughes lay on

nearby Caballo Island, and contained 13 heavy guns, while further south

on El Fraile island was Fort Drum, an island which had been leveled and

reformed into a "concrete battleship," with two steel turrets mounting

four 14-inch guns. Fort Frank, containing 14 large-caliber cannon on

Carabao Island, lay only 500 yards from the Cavite shoreline and was

perhaps most vulnerable to attack.

|

| |

Corregidor |

|

Middleside Barracks, March 1942. The barracks housed the reserve

company of the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines during the siege.

Austin C.Shofner Papers, Personal Papers Collection, MCHC

|

At 1000, 26 December, the 4th Marines began to move to Corregidor. More

than 400 Marines of the 1st Separate Marine Battalion were loaded on

board lighters and taken across the channel. They were then transported

by narrow gauge railway to Middleside Barracks. The forward echelon of

the Headquarters and Service Companies and the 2d Battalion loaded on a

minesweeper and lighters just after darkness the following day. Shortly

after midnight on 27 December, the 336 Marines and their equipment were

completely unloaded on Corregidor.

Two days later at

2010, the 1st Battalion and the remainder of the regiment completed the

transfer to Corregidor's North Dock. A 1st Battalion Marine private

busily carried a box of .30-caliber ammunition weighing more than 96

pounds to the dock. Lieutenant Colonel Beecher stepped in front of the

sweating Marine and took the box out of his hands. He then dropped the

ammunition off the dock into the water. The private stared dumbfounded

as Beecher informed him, "You're carrying blanks; we are not using them

anymore." The 4th took six months of rations for 2,000 men, 10 units of

fire for all weapons, a two-year supply of summer clothing, and

medicines and equipment for a 100-bed hospital, to Corregidor.

Marines were first

quartered in the concrete barracks on Middleside. When they inquired of

their Army comrades about protection from bombing, they were assured the

barracks were bombproof. Captain John Clark wrote later, "A feeling of

safety and security came over us as we reached the Rock. We were told it

was impregnable, and that we had nothing to fear from Japanese attack."

At 0800, 29 December,

Colonel Howard reported to Major General George F. Moore, commanding the

Harbor Defenses of Manila and Subic Bays. He was immediately appointed

commanding officer of beach defense, Corregidor. Howard then began a

prompt inspection of the current beach defenses.

|

|

|

First Bombing |

|

Japanese aircraft prepare to bomb Corregidor.

Photo courtesy of

Dr. Diosdado M. Yap |

At 1140 that same

day a flight of Japanese aircraft approached Corregidor. Air-raid sirens

sounded, but most of the 4th Marines paid little attention to them,

believing in the safety of Corregidor's antiaircraft defenses.

Lieutenant Sidney Jenkins remembered, "bombs screaming to earth with

shattering explosions, the crack of AA guns, the neat 'plop plop' of the

AA shells bursting all over the sky . . . there we were, the whole

regiment flat on our bellies on the lower deck of Middleside Barracks."

Marines in the upper

decks of Middleside Barracks sprinted for the lower deck for protection.

Most of the bombs that hit the building exploded on the second and third

decks, but Private First Class Don Thompson and 20 other Marines on the

first deck felt an explosion and a shower of cement dust. He looked up

and saw blue sky though a hole in the ceiling of the supposedly

bombproof barracks. Bombs continued to fall for the next two hours.

Corporal Verle W. Murphy died of multiple wounds to the head and chest

while trying to clear the building, and nine Marines were wounded in the

attack.

Private First Class

Charles R. Greer and Private Alexander Katchuck noticed two wounded men

in an abandoned truck. Greer and Katchuck left their shelter and drove

the truck to the hospital despite the falling bombs. They were awarded

Silver Star Medals, the first Marines to be awarded an Army decoration

in World War II, and the first to be mentioned in General MacArthur's

dispatches.

Bombs destroyed or

damaged the hospital, antiaircraft batteries, Topside and Middleside

Barracks, the Navy fuel depot, and the officers club. Smoke cast a black

pall over the island as numerous wooden buildings caught fire. Power,

water, and communication lines were disrupted. Total casualties on

Corregidor mounted to 20 killed and 80 wounded.

After the Japanese

bombing ended, the 4th Marines was assembled in front of the barracks to

ascertain casualties. As the men stood in formation, someone dragged a

sea bag down the stairs of the barracks, which made a noise like falling

bombs. Instantly, the men broke and ran "pell mell back into the safe

barracks" only to reemerge laughing once the origin of the sound was

determined.

Japanese bombers

reappeared over Corregidor at 1134, 2 January and bombed the island for

more than three hours. Private First Class Verdie G. Andrews was killed

by debris from the explosions and six other Marines were wounded.

Periodic bombing continued over the next four days resulting in one

Marine killed and another wounded. Only two more raids occurred in

January allowing the Marines to improve their positions considerably. On

29 January Japanese aircraft dropped only propaganda leaflets which

greatly amused the beach defenders.

|

|

|

Deployment |

|

Five

members of the 4th Marines pose for the camera on Corregidor. All

Marines were required to carry their gas masks at all times should the

Japanese use chemical agents.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) W-PHI-2

|

On 29-30 December the 4th Marines moved from its barracks into field

positions. The 1st Battalion took the east sector, from Malinta Hill to

Hooker Point on the tail of the island. The 2d Battalion moved into the

west sector and the 1st Separate Marine Battalion was assigned the

middle sector. On 1 January 1941, this battalion was officially

redesignated 3d Battalion, 4th Marines. Forty four Marines of the

battalion were detailed for antiaircraft defense for Batteries Wheeler

and Cheney. In addition, 46 Marines in two platoons of the 3d Battalion

under Second Lieutenant Frederick A. Hagen were deployed with .30- and

.50-caliber machine guns to provide antiaircraft fire and beach defense

of Fort Hughes. Another 14 Marines of the 3d Battalion were deployed to

Fort Drum for the same purpose.

Work began rapidly on

construction of beach defenses. Typical was the reaction of Lieutenant

Colonel Beecher when he first inspected his defense area. He later

wrote, "The task confronting us was appalling. With 350 men there were

3,500 to 4,000 yards of possible landing beach to defend." The Marines

began to build barbed wire barriers, tank traps, bunkers, and trench

systems. Working parties began at first light in the morning and halted

only at noon for a rest period in place of lunch. The work progressed

well, slowed only by Japanese shelling, bombing, and darkness.

Tools were carefully

guarded, as Lieutenant Jenkins remembered, "We took care of our tools

like gems." The Marines ran short of sandbags, so discarded powder cans

from the coastal artillery guns were filled with dirt and used in their

place. Bottles were filled with gasoline to make "Molotov cocktails," to

be dropped over cliffs on the Japanese. Empty gasoline drums were filled

with dirt and rock and set up as tank traps on trails leading from the

beach. Each position was carefully camouflaged for protection and dummy

positions were also constructed to attract enemy fire.

Marines of Company B

located Army aircraft bombs, and wooden chutes were constructed to drop

the bombs on landing areas. A second line of defense and reserve

positions were also built behind the front line beach defenses, with the

hope of eventual reinforcement.

|

|

|

The Bombardment Continues |

|

An unexploded bomb at Middleside, Corregidor, March 1942.

Austin C. Shofner Papers, Personal Papers Collection, MCHC

LtCol Herman R. Anderson stands on the beach on

Corregidor with the assembled officers of 2d Battalion, 4th

Marines and several Filipino officers. Note the thick layers of

oil on the beaches from ships sunk in Manila Bay.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 58736

|

On 6 February, Japanese artillery opened fire on Corregidor and the

fortified islands from positions in Cavite Province. The forts were

shelled eight more days and bombed twice in February. Occasional

shelling and bombing hit the fortified islands until 15 March, when the

Japanese began preparations to renew their offensive on Bataan. The

bombing and artillery raids now continued unabated until the end of the

siege. The Japanese conducted attacks spaced over every 24-hour period

after 24 March to prevent any rest by the defenders. Japanese harassing

artillery fires, conducted every 25-30 minutes throughout the night,

caused the Marines to dub the annoying cannon "Insomnia Charlie." The

artillery spotting balloon over Bataan was nicknamed "Peeping Tom."

The events of 30

March typify the constant Japanese bombardment. There were two periods

of shelling, beginning at 0950 and 1451, and six bombing raids,

beginning at 0040 and spaced throughout the day. One Marine, Private

First Class Kenneth R. Paulin of Company M, 3d Battalion, was killed

during the day by shellfire from the Cavite shore. The bombing raids

finally ended at 2205. The attacks were renewed at 0102 on the same

schedule, except 10 bombing raids occurred on 31 March.

At this time, the

major problems facing Major General Jonathan Wainwright, USA, commander

of U.S. Forces on the Bataan Peninsula, were dwindling food supply and

an increased disease rate. By March, the daily ration of food for the

men on Bataan was 1,000 calories with food for Corregidor rationed to

last until the end of June 1942. On 27 March, Wainwright telegraphed Mac

Arthur in Australia to report the June deadline and asked for supplies.

He also stated that "with ample food and ammunition we can hold the

enemy in his present position, I believe, indefinitely"

On 1 April, General

Wainwright recognized that little or no food could arrive through the

Japanese blockade and ordered a new reduced ration. The 4th Marines and

other defenders of Corregidor now consumed 30.49 ounces of food per day:

8 ounces of meat, 7 ounces of flour, 4 ounces of vegetables, 3 ounces of

beans and cereals, 2.5 ounces of rice, 3 ounces of milk, and

approximately 3 ounces of miscellaneous food stuffs.

"We were hungry all

the time," remembered Private First Class Ben L. Lohman, "We ate mule

meat . . . when the mules were killed in the bombing . . . they'd bring

the carcasses down and we'd eat 'em." Drinking water was distributed

only twice a day in powder cans, but bombing and shelling often

interrupted the resupply. The staple food for the 4th Marines was

cracked wheat, sometimes made into dumplings, sometimes served with

syrup. The continued lack of a proper diet created major problems for

the 4th Marines, as men were weakened and lacked reliable night vision.

Some Marines lost up to 40 pounds during the bombardment.

On 9 April, Bataan

fell to the Japanese after a final offensive broke through the USAFFE

defenses trapping more than 75,000 men. Battery C managed to escape at

the last minute, but the Marine guards at USAFFE headquarters and the

Air Warning Detachment were taken prisoner, and endured the infamous

Bataan Death March. The Japanese wasted little time before focusing

their attention on Corregidor, intensifying their bombardment of the

island the same day Bataan fell.

Although food was in

short supply on Corregidor. ammunition was relatively plentiful. As of 7

April, the island had 5,177,900 rounds of armor piercing, clipped, and

tracer .30-caliber ammunition and a total of 161,808 rounds of

.50-caliber ammunition. Gen Wainwright wrote, "Our flag still flies on

this beleaguered fortress." and added in his memoir, "I meant to see it

keep flying."

|

|

|

Reinforcements |

|

A Marine shows his friends his portion of a resupply of precious

cigarettes brought into Corregidor by submarine.

A new supply of cigarettes has just arrived in the Philippines

and the Marines are given their ration along with chow.

Marines break for one of their two meals a day on Corregidor. |

As men became available on Corregidor from January until after the fall

of Bataan, they were integrated into the 4th Marines to support beach

defense. In February, 58 sailors formerly of the USS Canopus were

organized as a reserve company Lieutenant Clarence Van Ray with Platoon

Sergeant Leslie D. Sawyer and Sergeant Ray K. Cohen trained and equipped

the sailors into an efficient fighting force. Ten Marines and 40 more

sailors were added to the company after the fall of Bataan.

The largest group of

reinforcements arrived after the fall of Bataan. In the days following 9

April, 72 officers and 1,173 enlisted men from more than 50 different

organizations were assigned to the 4th Marines, making the Marine

regiment one of the most unusual units in Marine Corps history. These

reinforcements included members of the Navy, the Army, the Philippine

Army and Philippine Scouts. Sailors stranded on land after the loss of

their ships found themselves alongside engineers, tankers, and aviators

whose units were captured on Bataan. Filipino Scouts were assigned with

members of the islands' Constabulary to the 4th Marines. Unfortunately,

very few of the reinforcements were trained or equipped for ground

combat. By 29 April, the 4th Marines numbered 229 officers and 3,770

men, of whom only about 1,500 were Marines.

The

Formation of the 4th Battalion

With Bataan on the

brink of falling, Captain John H. S. Dessez, the commander of the Navy

Base at Mariveles requested permission to transfer his 500 sailors to

Corregidor. Approval was granted with the condition that these men would

be part of the beach defense force. On 10 April, the 4th Battalion was

formed under the command of Major Francis H. "Joe" Williams. His command

was built with nine Army officers and 16 Navy officers and warrant

officers commanding 272 enlisted men. This joint service battalion

bivouacked in Government Ravine near Battery Geary and began to train

for ground combat.

Four companies were

organized in the battalion and lettered Q, R, S, and T. Companies Q and

R were commanded by Army officers and S and T by Navy officers. Rifles

still packed in cosmoline, a greasy protective coating, were issued to

the sailors. This presented interesting cleaning problems to the

inexperienced mariners. However, rifles were all that was issued to the

battalion in the way of equipment. There were no helmets, cartridge

belts, or even first aid kits.

Williams at once

began weapons training for his sailors. With no rifle range available,

the blue-jackets used floating debris in Manila Bay as targets on which

to sight in their rifles. Some of the Navy personnel had not fired a

weapon in almost 20 years. Training proceeded with cover and

concealment, and small unit tactics. Evening lectures were given by men

experienced in combat on Bataan. The accelerated infantry training by

the battalion was punctuated by the daily shelling and the fact that

each man felt "that this battalion would be used where the going was the

roughest . . . . The chips were down and there was no horseplay"

|

|

|

1st Battalion Defenses |

|

Marines teach Filipino aviation cadets the fundamentals of a

water-cooled .30-caliber Browning machine gun. |

Lieutenant Colonel Beecher now commanded 360 Marines, 500 Filipinos,

approximately 100 American sailors, and 100 American soldiers, totaling

1,024 effective fighting men. These troops were armed with the 1903

Springfield rifle, grenades, BARs, four 37mm guns, and eight .30-caliber

machine guns. A few 60mm mortars were available, as well as .50-caliber

machine guns taken from immobilized ships. They were emplaced to defend

the beaches. Additionally the Philippine Scouts had mounted a few 75mm

guns. Initially, the 37mm and 75mm guns could not be traversed quickly

enough that a fast moving boat could not easily escape their fire.

The Japanese shelling

caused serious damage to the beach defenses, and casualties among the

officers and men of the battalion, but most of the heavy weapons were

still intact. As of 1 May the battalion had lost only four machine guns

and eight cases of .30-caliber ammunition. Far more serious was the loss

of the water supply and a complete loss of the field communication

lines. Caches of rations were buried or received direct hits from lucky

shells. Casualties among officers and men were equally serious: Major

Harry C. Lang, commanding Company A, was killed; Captain Paul A. Brown

of Company B and one of his platoon commanders were wounded; one of

Company D's officers was wounded; and three Army officers with the

reserve company also were wounded. Army officers replaced the commanders

but the men had little confidence in them. This acute loss of

experienced leaders would be critical in the coming fighting.

The area held by the

1st Battalion was heavily wooded when first occupied in December and

dotted with coastal artillery barracks and other buildings. By early May

the area was completely barren of vegetation and scattered with the

ruins of shelled buildings. Sergeant Louis E. Duncan later remembered,

"there was dust a foot thick," covering the entire area.

On 1 May Beecher had

reported to Colonel Howard that the beach defenses on the eastern

portion of the island were practically destroyed by the Japanese

bombardment and that repair under the continuing fire would be

impossible. Beach wire had been repeatedly holed, tank traps filled in,

and all the heavy guns of the 1st Battalion were in temporary

emplacements as the initial ones had been spotted and destroyed by the

enemy. The Japanese fire was so accurate that the men could be fed only

at night.

Colonel Howard told

this to General Wainwright, who said only that he would never surrender.

When Howard told Beecher this, he replied, "I pointed out to Colonel

Howard that nothing had been said about surrender; I was merely

reporting conditions as they existed in my sector."

|

|

|

Japanese Preparations |

|

A Marine platoon sergeant of the 4th Marines instructs Filipino

cadets in the use of the Lewis machine gun.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 115.07A

LtCol Curtis T. Beecher and his runner pause during one of his daily

inspections of 1st Battalion defenses.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 58735

Col Samuel L. Howard, right, inspects the beach defenses on

Corregidor with LtCol Herman R. Anderson, left, commander of 2d

Battalion, 4th Marines, and MajGen George F. Moore, USA, center,

overall commander of the Corregidor defenses.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC)

Phi-9

|

The enemy bombing and shelling continued with unrelenting ferocity.

Japanese aircraft flew 614 missions from 28 April until 5 May dropping

1,701 bombs totaling 365.3 tons of explosive. At the same time 9 240mm

howitzers, 34 149mm howitzers, and 32 other artillery pieces pounded

Corregidor day and night. Most of the Japanese artillery was based on

Bataan with one reinforced battalion firing from Cavite Province.

On 2 May, a 240mm

shell exploded the magazines of Battery Geary, causing massive

casualties to the Army crews manning the guns. A Marine rescue party ran

to assist in clearing the casualties from the resulting fires. Major

Francis H. Williams and Captain Austin C. Shofner were the first two

Marines into the battery and both were seriously burned about the hands,

face, and ankles in rescuing survivors from the blaze. Both officers

refused to be evacuated.

On 29 April the

61st Infantry Regiment of the 4th Imperial Japanese Army Division

was selected to be the first force to be landed on Corregidor.

Supporting the infantry were elements of the 23d Independent Engineer

Battalion and the 1st Battalion of the 4th Engineer

Regiment. Once on shore, elements of the 1st Company, Independent

Mortar Battalion, the 51st Mountain Gun Regiment, and the

3d Mortar Battalion would provide gunfire support.

The 61st Infantry

and attached units, titled Left Flank Force, was to land on the

tail of Corregidor on the evening of 5 May This 2,400-man landing force

would seize Kindley Field and then capture Malinta Hill. The following

night a second reinforced regiment of the 4th Infantry Division

would land on Morrison and Battery Points. The two forces would then

join for the capture of Topside.

Intelligence

On the evening of 4

May a Philippine civilian arrived in a small fishing boat on the beach

at Corregidor. The civilian carried a message from Philippine

intelligence on Bataan, and was promptly carried to Lieutenant Colonel

George D. Hamilton, the regimental intelligence officer. Hamilton called

for Sergeant Harold S. Dennis of the intelligence section to read the

note aloud, as he was having difficulty disciphering the message. Dennis

read, "Expect enemy landing on the night of 5/6 May." Hamilton quieted

Dennis, saying, "Hush, hush, hush, don't say another word! Do you want

to start a panic?" Hamilton took Dennis with the note to Colonel Howard

who listened as the note was read aloud a second time. In the morning of

5 May Howard called a meeting of all the regiment's senior officers.

Once assembled, Howard told them the contents of the note from Bataan.

The Japanese were expected to make their attack that night or the

following day.

There followed a

discussion of the probabilities of the landing. If the Japanese were

expected that night, the beach positions would be 100% manned at

nightfall. If the landing took place at dawn, the positions would be 50%

manned until dawn so the men could eat and rest for the coming attack.

Curtis asked the assembled officers for their opinions, which was

followed by a spirited discussion. Curtis then called for a vote, which

was unanimous for the men to sleep until one hour before dawn and then

fully man the defenses.

Colonel Howard then

spoke and asked for the opinion of Sergeant Dennis, the only enlisted

man in the room. Dennis had studied Japanese tactics in China and said

that enemy landings were invariably made at night, one hour before the

full light of the moon. Colonel Howard thanked him for his opinion, but

did not change the regiment's orders. The men would be allowed to sleep

for a predawn landing.

Major Max W.

Schaeffer commanded the regimental reserve, which consisted of two

companies lettered O and P, formed mainly from Headquarters and Service

Company's personnel. Schaeffer's would be the first unit to move to any

Japanese landing on Corregidor. At 1700, 5 May he made his final

preparation for the night. Major Schaeffer summoned Sergeant Gerald A.

Turner to his headquarters. The sergeant reported by asking "Well,

Major, what's the trouble now?" Major Schaeffer replied, "It may be a

long, long night for you. The reason I've called you down here is

because we need a 2d platoon, and you're it." He made Turner a

lieutenant and gave him command of 30-35 Filipino army officer cadets

formed into a platoon of three squads. "Don't go out and try to be a

hero," cautioned Schaeffer, "I want you to look after these kids and

take care of them." Even with the addition of Turner's platoon, the

regimental reserve numbered less than 500 men.

|

|

|

The Landing |

|

A Japanese artillery piece on Bataan pounds Corregidor, April 1942.

Photo

courtesy of Dr. Diosdado M. Yap

Col Gempachi Sato, who commanded the Japanese forces which

landed on Corregidor on 6 May, is here planning that invasion.

Photograph courtesy of 61st Infantry Association

Bataan Peninsula is viewed across Manila Bay from the North Dock

area on Corregidor. The masts and stack of a ship sunk in the

bay are visible in the middle of the photograph.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 311-T

SSgt William A. Dudley physically lifted the trails of his 37mm

gun to fire down at the Japanese landing craft on the night of

5-6 May 1942. Dudley is the Marine second from the left in the

second row.

William C. Koch Papers, Personal Papers Collection, MCHC

|

At nightfall on 5 May

Colonel Gempachi Sato assembled his Left Flank Force at Limay on

the Bataan Peninsula. The gathered troops "sang softly the high thin

haunting melody of 'Prayer in the Dawn,'" and then climbed into 19

landing craft for the assault. The landing craft varied in size, the

smallest carrying 30 men and the largest 170. More important, five tanks

of the 7th Tank Regiment were also embarked in two landing craft.

The landing craft and barges approached Corregidor in a three-line

formation with expected landfall at 2300, shortly before the rise of the

moon.

At 2240 the artillery

shelling concentrated on the north shore beach defenses in the 1st

Battalion sector. At 2300, supplies of food and water were just reaching

the beach positions when landing boats were reported offshore. A second

artillery concentration pounded the beach defenses for 6-7 minutes. The

shelling was particularly intense, ending with phosphorous shells. Three

to four minutes of silence followed the last shell when word reached

Beecher at battalion headquarters that seven Japanese landing craft were

nearing the beach. The initial Japanese landing of 790 men of the

reinforced 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry was headed for the

beaches from Infantry Point to North Point.

Captain Lewis H.

Pickup of Company A watched from his command post as the first force of

landing craft in echelon headed for his company's positions.

Searchlights picked up the landing craft and the 1st Battalion commenced

firing. The 37mm guns had no trouble tracking the landing craft, as

Sergeant Louis E. Duncan had altered the traversing mechanism so it

could move more freely Gunnery Sergeant William A. Dudley held up the

trails to his 37mm gun to fire down on the incoming boats.

Private First Class

Silas K. Barnes heard the boat motors from his machine gun position on

Infantry Point and for a few moments was able to hit the approaching

landing craft that were illuminated by the search lights. He effectively

enfiladed Cavalry Beach and cut down many of the Japanese soldiers as

they came ashore. The Japanese struggled in the layers of oil that

covered the beaches from ships sunk earlier in the siege and experienced

great difficulty in landing personnel and equipment. Unfortunately

Barnes' and one other machine gun position were all that remained of 13

machine guns from Infantry Point to North Point. The rest had been

destroyed by the Japanese bombardment.

The 1st Platoon,

Company A, commanded by First Lieutenant William F. Harris, defended the

beach from Infantry to Cavalry Points, while the 2d Platoon under Master

Gunnery Sergeant John Mercurio held the line from Cavalry to North

Points. "I've got word that landing boats will attempt a landing,"

Harris told his men, "They'll be coming in here someplace. Fix

Bayonets." He ordered Private First Class James D. Nixon to go to the

cliff overlooking the beach, and report on the location of the Japanese.

Nixon looked at the beach and saw Japanese troops coming ashore only 30

feet away. The Marines placed a heavy fire on the Japanese as they

climbed the steep cliffs and tossed "Molotov Cocktails" down on the

landing craft. In the darkness, however, the Japanese succeeded in

bypassing many of the Marine positions.

Master Gunnery

Sergeant Mercurio's 2d Platoon was spread thin covering the beach area,

with many of his positions right on the water. "At high tide," recalled

Corporal Edwin R. Franklin, "I could reach out and touch the water." The

landing craft were only 100 yards away from the beach when Japanese

flares lit up the night. The 2d Platoon began firing, but the Japanese

were too close to halt the landing. A landing craft beached in front of

Franklin's position and enemy troops began coming ashore. Mercurio,

armed with only a pistol, killed a Japanese soldier "so close he could

have touched him," as the Japanese overran the beach defenses. The

fighting became particularly bloody, "with every man for himself,"

remembered Franklin. The Japanese 50mm heavy grenade dischargers or

"knee mortars" were particularly effective at close range, and the

overwhelming numbers of Japanese infantry forced Mercurio's men to pull

back from the beach.

Corporal Joseph Q.

Johnson, a 31st Infantry soldier attached to the 2d Platoon, remembered,

"the gun next to me chattered, and glancing to my right, I saw its

targets, small, fleeting, darting in the shadows." Johnson fired two

belts of machine gun ammunition and was firing a third one when a

grenade landed 20 yards away. A second grenade landed closer, and rifle

fire also hit Johnson's position. When a third grenade landed only 10

yards from the gunpit, Johnson ran to the next machine gun position and

found the two occupants dead. He kept moving, crawling along the beach

with two other survivors of his platoon, toward Kindley Field.

The survivors of the

2d Platoon found themselves surrounded by the advancing Japanese as they

tried to reach safety Corporal Franklin saw a grenade land in the trail

in front of him, which exploded and knocked him to the ground with a

head wound. Franklin next hazily saw a Japanese soldier charging with

fixed bayonet. The Marine said to himself, "I ain't going this f*****

way" and jumped up to engage the enemy with his own bayonet. Franklin

was stabbed in the chest, but succeeded in killing the Japanese soldier.

He ran ahead down the trail past another enemy soldier, who shot

Franklin in the leg, but the Marine continued moving until he reached

Malinta Tunnel.

Lieutenant Harris was

forced to pull his platoon out of the area of Cavalry Point after the

Japanese overran Mercurio's platoon. Most of the men fought on their own

through the night. Private First Class Nixon moved toward the high

ground of Denver Battery, when he encountered a Japanese soldier,

"eyeball to eyeball." Both men charged with fixed bayonet, and in the

ensuing struggle, Nixon was able to wound the Japanese soldier in the

side. He left his enemy in the darkness and moved toward the sound of

firing.

After facing 30-45

minutes of defensive firing the landing craft seemed to abandon their

attempts to land and retired to the bay. The firing then subsided.

Unknown to Captain Pickup, most of the 1st Battalion, 61st Infantry

was ashore in 15 minutes and the barges were returning to Limay. The

Japanese sent up a flare to signal a successful landing at 2315. In 30

minutes, Colonel Sato had his men off the beach and moving inland.

The 785 men of the

reinforced 2d Battalion, 61st Infantry were not so successful.

The Japanese planners had not reckoned with the strong current in the

channel between Bataan and Corregidor and the battalion landed east of

North Point where all defensive positions were still intact. The craft

also hit the Corregidor beach 10 minutes after the 1st Battalion,

and the Marines were ready and alert for the attack. The Japanese came

under heavy fire for the next 35 minutes, losing eight of 10 landing

craft on the shore and one more sinking after pulling off the beach.

Private First Class

Roy E. Hays manned a .30-caliber machine gun nestled in the cliffs

overlooking the beach area at Hooker Point. He could see the barges

approach his position, but was ordered to hold fire until the landing

craft came closer. Hays decided, "We're not waiting any longer," and

opened a devastating fire at point blank range. This was instantly

followed by accompanying fires from all the weapons positions along the

beach.

The Japanese who did

get ashore were crowded in most cases on beaches that were only 30 feet

wide backed by 30-foot-high cliffs. Most of the officers were killed

early in the landing, and the huddled survivors were hit with hand

grenades, and machine gun and rifle fire.

Private First Class

David L. Johnson remembered a sailor named Hamilton firing a twin

.50-caliber machine gun up and down the beach, "like shooting ducks in a

rain barrel. The Japanese would run up and down the beach," remembered

Johnson "and each time there would be less men in the charges. Finally

they swam into the surf, and hid behind boulders." For the remainder of

the night, only small bands of Japanese were able to scale the cliffs

and engage the Marines.

Captain Pickup went

out to check his platoons, assuming the attack had been repulsed. He

then learned that some of the landing craft had made it ashore in the

North Point area and Japanese troops were moving inland. At the same

time, Beecher sent runners to all of his company commanders alerting

them to the landing. As planned, if the enemy penetration was

successful, Company A would withdraw and join Company B in a line based

on Battery Denver, holding the tail of the island from the Japanese.

Before the line could be formed, the Japanese captured Denver at 2350

and were discovered digging in. Colonel Sato had led his 1st

Battalion soldiers to Denver Hill almost unnoticed.

|

|

|

Counterattack |

|

A postwar view of the Cavalry and Infantry and Point landing

beaches on Corregidor and Kindley Field. Note the Denver Battery

ridge on the left of the photograph.

National Archives

Barbed wire entanglements on the beach at Corregidor. Most of

these were destroyed at the time of the Japanese landing. |

Platoon Sergeant William Haynes led his 3d Platoon, the reserve platoon

from Company B, from the south beaches at Monkey Point over to reinforce

Company A. Haynes kept his men together in the darkness and reached the

beach area. Hearing Japanese voices ashore, the platoon moved and fired

trying to make contact with the Japanese, but they were firing only at

the voices. After an hour the platoon became scattered in the darkness

and each Marine fought the rest of the night on his own.

Captain Pickup had

only just returned to his headquarters, when he discovered the enemy on

Denver. His first reaction was to pull a platoon off the beach and

retake the battery but in discussion with First Lieutenant William

Harris, he decided to keep his beach defenses intact and await

reinforcements. Marine Gunner Harold M. Ferrell went to 1st Battalion

headquarters to alert Captain Noel O. Castle, commanding Company D, to

the Japanese landing. He had sent a runner to Denver Battery where he

found Japanese in the gun pits. Castle, a distinguished marks man and

pistol shot who carried two pearl-handled .45-caliber pistols, assembled

the Marines of Headquarters Company and the few Marines available of

Company D to drive the Japanese off of Denver Hill.

Castle dispatched

Sergeant Matthew Monk with 15 drivers and cooks to occupy an abandoned

beach defense position and secure his left flank. "Do the best you can,"

he ordered Monk, "Keep the Japanese out of the tunnel." Castle also

scouted the reserve stations at critical road junctions, and cautioned

the men, "Maintain positions." He then gathered his men for the counter

attack to Denver Battery, declaring, "Let's go up there and run the

bastards off."

Ferrell warned Castle

from leading the attack himself, but the captain replied, "I'm going to

take these people up there and shoot those people's eyes out" and led

his men to the hill. Castle met the Marines falling back from the

Japanese advance, and joined in the battle. At 0140, the Japanese

attacked the water tower and ran directly into the reinforced platoon

led by Castle. The two forces collided in furious combat, practically

"face to face," remembered Corporal Joseph J. Kopacz. The Japanese

advance was halted but the Marine attack was bloodily repulsed.

Castle left the

battle line and ran to an abandoned .30-caliber machine gun, which he

put into working order, while "completely covered by enemy fire." Castle

opened a devastating fire with the machine gun, forcing the Japanese to

cover, which allowed the American advance to continue. The Japanese fell

back from the water tanks to the Denver Battery positions, but Castle

was hit by Japanese machine gun fire and killed. With their commander

down, the attack ground to a halt.

Captain Golland L.

Clark of Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, then ordered mortar fire

placed on the ridge and for 20 minutes Stokes mortars, converted to fire

81mm ammunition, pounded the Japanese positions. However, the Marine

with the range card which contained the coordinates which targeted the

entire end of the island could not be found throughout the night. The

mortar firing soon halted as stray rounds were impacting on Marine

positions on the other side of the hill. For the moment only scattered

Marines from every company in the 1st Battalion held the Japanese from

moving on to Malinta Tunnel.

Gunner Ferrell put

together what few men he could find from Company D and formed a line to

prevent the Japanese from moving down from the high ground and taking

the northern beach defenses from the rear. Marines from Headquarters

Platoon, Company A, joined the battle on their own. First Sergeant Noble

J. Wells formed 25 to 30 Marines on line to prevent the Japanese from

moving along the north road. The Japanese soon attacked, screaming,

"Banzai! Banzai!" and reached within 15 to 20 yards of the Marine

position before being turned back. The Japanese then tried to infiltrate

behind Wells' men. He posted two Marines to guard the communication

trench. Corporal Howard A. Jordan heard a noise and shouted, "Who goes

there?" A voice responded, "Me Filipino, got hurt foot," and a figure

began to run. Both Marines opened fire, and dropped the man who turned

out to be a Japanese soldier. Corporal John H. Frazier later remarked,

"Didn't have to worry about that foot anymore."

Before midnight,

Lieutenant Colonel Beecher committed his battalion reserve, a platoon of

30 Philippine Scouts, but the Japanese were obviously firmly ashore and

more reinforcements were needed to drive the enemy back to the beaches.

Lieutenant Colonel Samuel V. Freeny organized a platoon of men, gathered

from Malinta Tunnel, to reinforce the beleaguered 1st Battalion. One of

the U.S. Army enlisted men complained, "I've never fired a rifle before,

I'm in the finance department." Freeny replied, "You just go out and

draw their fire and the Marines will pick them off." With the 1st

Battalion fully committed, Colonel Howard ordered the regimental reserve

under Major Max Schaeffer to report to Beecher. The 4th Battalion was

alerted to be ready to respond should more men be needed.

|

|

|

Movement of the Regimental Reserve |

|

The landing area from Cavalry to Infantry Points, Corregidor.

Photograph courtesy of 61st Infantry Association

A view of the 4th Marines beach defenses, at this point

consisting of sandbagged bunkers and trenches. Note that the

Japanese bombardment has taken every leaf from nearby trees.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) OOR-11004

|

At the sound of machine gun fire, Major Schaeffer alerted his two

companies which formed the regimental reserve, and sent Sergeant

Turner's Filipino cadet platoon in advance to Malinta Tunnel. Shortly

before midnight, he moved the rest of his men to the tunnel. The Marines

pulled on their bandoliers of ammunition, fastened grenades to their

cartridge belts, and as Private First Class Melvin Sheya remembered,

said to each other, "Well, here goes nothing." The two companies moved

along the South Shore Road under Japanese artillery fire, but lost only

a few men before reaching the tunnel.

When Sergeant

Turner's platoon reached Malinta Tunnel, he found the passage blocked by

hundreds of "tunnel rats," soldiers who had no organization on the

island and lived in the safety of the tunnel. These men wouldn't clear

the corridor for the regimental reserve to pass into. Turner ordered his

men, "Fix bayonets, boys, let's give them a nudge." The main passage of

the tunnel was soon cleared.

Lieutenant Colonel

Beecher informed Schaeffer of the situation on Denver Hill as the

Marines drew more hand grenades and Lewis machine gun magazines from

caches planted against an eastern attack. All proceeded according to

plan. A few Marines and sailors from the tunnel joined the column as

ammunition bearers. At 0100 Major Schaeffer gave his company and platoon

commanders orders to counterattack and drive the Japanese off the tail

of Corregidor. Company P would advance down the road toward Kindley

Field and upon meeting resistance would deploy to the left of the road

while Company O would move to the right. Together the companies would

sweep to the end of the island. Officers of the 1st Battalion would lead

the two companies into position.

At 0200 the two

companies of the regimental reserve deployed down the road leading east

from Malinta Tunnel. Sergeant Turner's platoon again led the advance

from the tunnel, literally running into Captain Golland L. Clark, 1st

Battalion adjutant, who was directing reinforcements to the battle area.

"Oh, Turner, what's your unit?" Clark asked. "It's my platoon. They sent

me out here and I'm supposed to contact you," answered Turner. "I want

you to go down this road," Clark ordered, "just keep going as far as you

can until you make contact with D Company."

Sergeant Turner's

platoon moved less than 200 yards when a green flare went up right above

the men. Turner stopped, turned, and called out, "Hit the deck," as

Japanese artillery began raking the area. The platoon went to ground and

was prevented from going to the Denver Battery fight. Rifle fire also

ranged into the position and continued to pin the platoon down.

Major Schaeffer's

main force followed behind Turner. Shots were soon exchanged between

Marines of the two companies. Cloaked in darkness it was impossible to

tell friend from foe. At a fork in the road, Company P turned left and

Company O took a right turn. First Lieutenant Hogaboom, commanding

Company P, soon ran into scattered Japanese fire and Captain Clark

ordered Hogaboom to deploy his men into line formation. Hogaboom soon

found that he had only his 2d Platoon. The other two platoons were

nowhere to be seen.

Company O, behind

Company P, had almost reached the fork in the road when they began to

take Japanese rifle and machine gun fire. Sergeant Carl M. Holloway

remembered, "we had been so accustomed to . . . heavy artillery fire and

bombs for so many months, that the bullets kicking up dust around our

feet seemed at times almost like rain drops hitting the dust." Flares

then lit up the night sky followed by a thunderous Japanese barrage. The

lead platoon was able to take cover in nearby bomb craters but still

lost eight men in the first few minutes of the shelling. The rest of the

company was caught in the open and cut to pieces. The 3d Platoon was

left with only six Marines unhurt while 2d Platoon had only five.

As soon as the

barrage lifted, Quartermaster Clerk Frank W. Ferguson advanced his 1st

platoon as ordered but came under heavy machine gun fire from Battery

Denver hill. Ferguson deployed his platoon to the left of the road and

tried to tie in with Company P. He believed that the two platoons behind

him would soon be up to anchor his right to the beach and to support his

advance. A few isolated Marines did reach him, but only a handful.

Ferguson then led his men up the hill into the face of concentrated

machine gun fire. The commitment of the regimental reserve was now

whittled down to two isolated platoons, each advancing unsupported.

At 0300 Ferguson's

platoon came to a halt on the hillside. The steep slopes were covered by

interlocking machine gun fire and despite three attempts, only a few

yards were gained. The 1st Platoon halted only 30 yards from the

Japanese positions and dug in. The battle now raged around the two

concrete water tanks on top of the ridge, just ahead of the Denver

Battery position. Ferguson's immediate concern was for his flanks and he

moved a Lewis gun and an automatic rifle to cover the road to his right.

His left still had no connection with Company P, but Quartermaster

Sergeant John E. Haskin brought up his five men of 3d Platoon and

Ferguson sent them to the left to extend that flank. Captain Chambers

ordered the five survivors of the 2d Platoon to Ferguson who also sent

them to his left. Soon word reached Chambers that Company P had been

joined.

While Ferguson was

battling for the hill, Lieutenant Hogaboom as advancing along the

coastal road toward the Japanese landing areas. He met a platoon of

Marines of Company A under Lieutenant Harris engaged in sweeping out

Japanese snipers from a wooded area. Harris agreed to support Hogaboom,

extending Hogaboom's left to the beach. Luckily, Hogaboom's 1st Platoon

found its way to the front and was placed in reserve. The three platoons

advanced, killing a few scattered Japanese soldiers until they hit the

Japanese main defense line in the draw extending from Battery Denver to

the northern beaches. Hogaboom's men were stalled by the Japanese fire

and even the 1st Platoon could deploy no further.

With no reserve and a

tenuous right flank, Hogaboom was forced to draw a squad to the right

rear. As he was deploying the Marines, Japanese landing barges appeared

from the sea bearing for the beaches on Hogaboom's left. The 1st

Battalion Marines on North Point opened on the barges spraying them with

.50-caliber machine gun fire. "The bullets smacking the armor of the

barges sounded like rivet hammers rattling away," remembered Hogaboom.

Private First Class Robert P. McKechnie took a Lewis gun to an overlook

and personally disabled two of the barges, leaving them drifting

aimlessly.

After savaging the

attempted landing, the Marines tried to advance to join the members of

the 1st Battalion at Cavalry Point, but the Japanese machine gun at the

head of the draw proved to be too well protected. The remnants of both

companies settled in their positions and then began a duel of American

grenades against the ammunition of the deadly accurate Japanese "knee"

mortars. Captain Robert Chambers, Jr., met with Hogaboom before dawn to

coordinate the battle line of the two companies. Both commanders agreed

that without reinforcements, the battle would soon go against the

Marines.

|

|

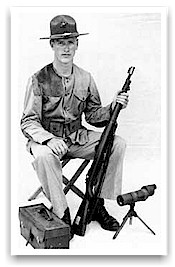

Capt Noel O. Castle, expert team shot with both rifle and pistol, was

killed leading the first counterattack on Denver Hill. He is shown here

at the Camp Perry matches in March 1937, when he was a member of the

Marine Corps rifle team. Department of

Defense Photo (USMC) 7563 |

Before midnight, Colonel Howard gave orders for the 4th

Battalion to prepare to move to Malinta Tunnel and replace the regimental

reserve. Major Williams had already alerted his men based on the view he had

of the east end of the island. The men of the battalion needed little

warning, having also watched the landing take place. At midnight Williams

had extra ammunition issued and all companies ready to move. At 0130 he

received Howard's order to shift to the tunnel and the 4th Battalion moved

at once.

The battalion marched in the darkness in two columns

along the road to the tunnel well spread out to avoid Japanese artillery

fire, but were delayed by a 20-minute artillery barrage and suffered a few

casualties. By 0230, Major Williams had his men into Malinta Tunnel and

awaited further orders.

At 0430 Colonel Howard decided to commit his last

reserves, the 500 Marines, sailors, and soldiers of the 4th Battalion. Major

Williams' men were long ago ready to move out, the Malinta Tunnel being

severely congested with a constant stream of wounded Marines from the early

fighting. Morale in the battalion was strained by the constant concussions

from the Japanese shelling outside and the proliferation of rumors in the

tunnel. Lieutenant Charles R. Brook, USN, remembered, "It was hot, terribly

hot, and the ventilation was so bad that we could hardly breathe."

Led by Major Williams, the battalion emerged from the

tunnel in platoon column. The men were suddenly subjected to a severe

shelling and casualties began to mount before the last company was able to

leave the tunnel. However, within 10 minutes, the battalion reformed under

fire and began to move forward. Another barrage soon struck, causing more

casualties and confusion. Minutes later, the column was again reorganized

and the advance continued. At 200 yards behind the line of the 1st

Battalion, Williams ordered Companies Q and R to deploy in a skirmish line

and guide to the left of the line. Company T repeated the orders and formed

on the right of Company R and guided to the right. Company S formed the

reserve.

The order of the battalion was prudent, for the main line

of resistance was badly in need of reinforcement. In the moonlight,

deployment into skirmish formation was difficult, but eventually

accomplished. Contact with the 1st Battalion was spotty at best and no

Marines were found in line ahead of Company R. Scattered parties of Japanese

soldiers had infiltrated behind the Marine positions all night and their

sniping proved worrisome to the inexperienced sailors. Both Companies Q and

R were receiving fire from ahead and behind as they moved into position.

In the confusion, two sailors, Signalman First Class

Maurice C. Havey and Signalman First Class Frank H. Bigelow, became

separated from their command and came upon an unmanned twin .50-caliber

machine gun overlooking the beach area. They manned the gun and opened fire

on the Japanese on the coastline for 30 minutes. Havey fired until the

barrels burned out and Bigelow then replaced them. Suddenly, Havey dropped

from the gun, turned and said, "I'm hit." He staggered to the rear toward

Malinta Tunnel while Bigelow stayed with the gun. Havey had travelled only

100 yards when he was killed by seven machine gun bullets across the chest.

|

|

A prewar view of Denver Hill from Malinta Hill. Note the water tank on

the hill.

National Archives

Japanese soldiers pause

amid the fighting on 6 May as they move their light artillery inland from

the beaches. Photograph

courtesy from 61st Infantry Association

Japanese troops move to the high ground on Corregidor's north shore

during the firefighting on 6 May.

Photograph courtesy of 61st Infantry

Association

These two water tanks were the focus of the heaviest 4th Marines

fighting on 6 May. The tank in the foreground overlooked the Denver

Battery positions and was where QMSgt John E. Haskin and SgtMaj Thomas

F. Sweeney died.

Photo courtesy of

61st Infantry Association

Col Sato confers with his staff during the fighting for Denver Battery

hill. The absence of an ammunition resupply threatened the success of

his landing.

Photograph courtesy of 61st Infantry Association

|

Attack

of the 4th Battalion |

|

Unbeknownst to the Marines, the Japanese troops on

Corregidor received reinforcements just before dawn. The 3d Battalion,

61st Infantry, engineers, and light artillery arrived with at least 880

men to join the battle. This force was originally scheduled to arrive at

0230, but the losses in landing craft in the initial attack forced the

delay. Even so, five tanks and most of the field artillery were left on

Bataan due to lack of landing craft. At 0530, three green flares signaled

the successful landing by the Japanese.

From 0530 to 0600 the four company commanders of the 4th

Battalion tried to put their men into position but were hampered by the

darkness, lack of knowledge of the terrain, and the lack of cohesion of the

1st Battalion. In some cases the 4th Battalion actually formed a line behind

the 1st Battalion positions with no knowledge of the Marines ahead of them.

Luckily, the Japanese artillery was strangely silent. Major Schaeffer came

out of the firing line to confer with Major Williams on the placement of the

reinforcements, asking, "Joe, what in the hell did you bring me?" Williams

responded, "I have my whole battalion here — or what's left of them. Where

is your unit? and what position do you want my battalion in?" Schaeffer lost

his composure for a moment and replied, "Joe, I don't know! . . . I don't

know where in hell my non coms are, I think they are all dead!" Williams

motioned a near by corpsman to check the major and said, "Dammit now, you

relax, I'll take over this situation." Schaeffer pulled himself together and

indicated the most needy area was the gap between his two companies. Company

S moved out of reserve and forward to fill the breach.

Major Williams and his staff armed themselves with rifles

and hand grenades and entered the front lines where the firing was the

heaviest. This command decision at times prevented tight coordination among

the companies as the commanders often would have little idea how to contact

the major. The dazed battalion settled into its positions and extended its

flanks to cover the island from end to end. A decision was reached to find

how many men had been lost in getting into position, but this effort was

unsuccessful. The best estimate of the strength of the battalion at that

time was about 400 men.

At 0600 Williams ordered his battalion to counterattack

at 0615, the break of dawn. In 10 minutes all companies were alerted and

jumped off promptly at the designated time. The order, "Charge," came down

the line and the Marines, sailors, and soldiers attacked with fixed

bayonets, "yelling and screaming . . . cursing and howling . . ." Gunner

Ferrell tried to use the 1st Battalion Stokes mortars to support the attack,

but again the rounds were too inaccurate for use. Companies Q and R rapidly

gained ground on the left, but Company S ran at once into heavy machine gun

fire and was halted after moving only 100 yards.

Company T also ground to a halt after gaining little

ground. The Japanese sent up flares which brought a prompt response from the

artillery on Bataan. In 10 minutes the gunfire halted and Company T resumed

the attack on the ground around Battery Denver, but machine gun fire quickly

halted the advance. A machine gun position on the north road was knocked

out, as was another in the ruins on Battery Denver Hill, but at heavy cost.

Major Schaeffer was pinned down in his command post by

these two machine guns and had lost contact with his men. When the fire was

silenced, he rose from his position, a mixture of dirt and blood from wounds

running into his eyes, blinding him. Despite his wounds, Schaeffer tried to

reorganize his men and explain to Williams what had happened. Major Williams

had Schaeffer cared for and calmly took control of the action.

Predictably, contact was soon lost between the two left

companies, Q and R, and the two companies on the right, S and T. The

companies on the left had outdistanced those on the right by 200 yards.

Williams halted Companies Q and R, ordering them to regain contact with the

stalled companies and try to break into the Japanese flank on Denver. The

two boat loads of Japanese soldiers left drifting by Private First Class

McKechnie, and now hung up off shore, were successfully destroyed despite

the poor marksmanship of the sailors in Company Q. At 0630 Williams began to

shift men to the right, which was hard-pressed.

Quartermaster Clerk Ferguson, now in command of Company

O, decided to attack the two machine guns which covered the beach road by

the flank. Ferguson, with six men, moved down the road covered for some

distance by the road embankment. Unfortunately, two new machine guns opened

on the party and they were bracketed by knee mortars. By the time Ferguson

was abreast of the first guns he had only one man left, Corporal Alvin E.

Stewart of the 803d Engineer Battalion. The two gave up the enterprise and

moved to the south side of the road to place rifle fire on the offending

machine guns.

The Japanese on top of the hill evidently thought they

were being flanked by a larger party of men and a reinforced platoon began

to file out of Battery Denver to counter Ferguson's move. The Japanese were

entirely in silhouette against the skyline and the two Americans by the road

had perfect targets. Ferguson later wrote "There wasn't a chance to miss

them — we were too close for that." Within seconds 20 Japanese soldiers were

killed or wounded. The Americans were so intent on firing that they didn't

notice a Japanese rifleman coming up behind them. Ferguson was shot by a

glancing bullet in the face, leaving blood streaming from his nose and

cheek. Stewart was able to pull him back to the Marine battle line without

further wounds.

One of the major impediments to the Marine attack was a

Japanese machine gun placed in a hole in the base of one of the water tanks.

Quartermaster Sergeant John E. Haskin and Sergeant Major Thomas F. Sweeney

ran under fire and climbed up the cement water tower in the predawn

darkness. The two Marines did not expect to survive the battle, and their

comrades knew that both would attempt some extreme action during the

expected fighting. Marine Gunner Ferrell talked to Sweeney as he led his men

into action that morning. Sweeney said as they parted, "Well, this is it.

We've been in the Marine Corps for 15 years and this is what we've been

waiting for. If I don't see you, that's the way it is."

The two Marines now lobbed grenades into the Japanese

positions, promptly destroying the machine gun in the water tank. Captain

Brook remembered, "A Marine sergeant . . . gathered an armful of hand

grenades and climbed to the top of a stone water tower near our front line.

From here, he threw them at a Japanese sniper position and succeeded in

knocking it out." Another Marine, Corporal Sidney E. Funk, was crawling

beside the water tank when he heard a voice call down, "Hey Funk, those

bastards are right over there in the brush. If I had enough hand grenades,

I'd blow the hell out of them." Funk had no idea who the voice belonged to

and quickly crawled away for cover.

Despite drawing fire to themselves, Haskin and Sweeney

continued to have some initial success, destroying at least one more machine

gun. However, their supply of grenades was soon exhausted and Haskin was

killed while reclimbing the tower with more ammunition. Sweeney was killed

soon after. The two "were very close friends in life," remembered

Quartermaster Clerk Frank W. Ferguson, "it was most fitting that they should

go out together."

The American advance on both the right and the left was

next halted by an enemy machine gun located in the gun pit of Battery Denver

near the water tower. From this commanding position the gun could hit any

movement from the north coast to the south. The gun drew the attention of

Major Williams who personally took on the gun with his Springfield rifle

with no result. At 0730 Lieutenant Bethel B. Otter, USN, commanding Company

T, took Ensign William R. Lloyd and four volunteers, armed only with hand

grenades, to take out the gun.

Under covering fire of the company, Otter crawled with

his volunteers to within 25 yards of the gun pit and lobbed grenades into

the position. For a few moments the weapon was silent, the gun crew dead.

Almost immediately the gun crew was replaced and all but one member of the

assault party was killed. With the gun still in operation, no movement

further east could be accomplished. Army Captain Calvin E. Chunn of the

battalion staff took over the company and led an advance on a group of

Japanese soldiers setting up a light artillery piece. As the company moved

forward, a shell struck amidst the command group, wounding Chunn and two

other officers. By 0900 the 4th Battalion was stalled and Williams sent to

Colonel Howard for reinforcements and artillery support to resume the

attack. Neither were available.

First Lieutenant Mason F. Chronister of Company B, on the

south shore beaches, could see in the growing daylight the Japanese holding

the high ground around Denver Battery. He organized his platoon with

volunteers from the Navy Communications Tunnel and Battery M, 60th Coast

Artillery, to attack the Japanese from the west at the same time Williams

was attacking from the east. The attack proceeded up the ridge, but hit

Japanese reinforcements from the recently landed 3d Battalion, 61st

Infantry, also moving up the hill. Lieutenant Chronister withdrew his

men from the larger force, and moved them along a trail, joining Williams'

line at the watertank.

|

|

|

Morning Battle |

|

|

During the morning action Major Williams fought beside his

men, moving from position to position along the line. Captain Brook remembered,

"He was everywhere along the line, organizing and directing our attack, always

in the thick of it, seeming to bear a charmed life. I have heard men say that he

was the bravest man they ever saw."

From 0900 until 1030 the fire fight proceeded without change

in position. The lines were so close that none of the companies could shift a

squad without drawing machine gun fire and artillery. All of the 4th Battalion

was fighting without helmets, canteens, or even cartridge belts. However, the

Marines had the advantage of being too close for the Japanese artillery to be of

use. Small parties of Marines occasionally were dispatched to take out Japanese

snipers who were firing into the rear of the Marine position from the beach

area.

The Japanese were now facing a serious problem, which

threatened to lose the battle for them. Each Japanese rifleman came ashore with

120 rounds of ammunition and two hand grenades. The machine gun sections carried

only two cases totalling 720 rounds of ammunition and three to six grenades. The

knee mortar sections had only 36 heavy grenades and three light grenades. A

large quantity of additional ammunition had been loaded on the landing craft due

to the expect ed problems in resupplying the force. However, the ammunition

crates had been hurriedly dumped overboard by the crews of the landing craft as

they grounded on Corregidor and now few boxes could be recovered in the murky

water. By morning most of the Japanese on Denver Hill were either out of

ammunition or very close to it. Many Japanese soldiers were now fighting with

the bayonet and even threw rocks at the Marines to hold the hill.

At 0900, Captain Herman Hauck, USA, reinforced the Marines

and sailors with 60 members of his Coast Artillery battery Williams placed the

soldiers on the beaches to his left where heavy losses had whittled away at his

strength. With the reinforcements some advance was made, but against strong

enemy resistance. Nevertheless, much of the fighting was done with the bayonet,

as the Japanese were running out of ammunition. The tide was beginning to turn

against the Japanese. As Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma reflected one year

after the surrender, "If the enemy had stood their ground 12 hours longer,

events might not have transpired as smoothly as they did."

The Japanese were able to set up a mortar battery on North

Point and opened with telling effect on Williams' left companies. Two squads

were sent out to flank the guns, but ran into machine gun fire which wiped out

almost the entire right squad. Three more squads were sent out, two to the left

and one to the right of the mortars. After heavy fighting and loss, the deadly

mortars were silenced.

The machine gun at the head of the draw at Cavalry Point also

had held up the progress of the advance. U.S. Army Lieutenant Otis E. Saalman of

the 4th Battalion staff was ordered by Williams to go to the left and see what

he could do to get the line moving. With the help of Captain Harold Dalness,

USA, Saalman took a party of volunteers up the draw to silence the gun. The

Americans crawled unobserved to within grenade range and then opened fire on the

enemy with rifles and grenades. One of the Japanese defenders picked up a

grenade and lifted it to throw it back at the Americans when it went off in his

hand. The gun was at last silenced and the way lay open to link up with the 1st

Battalion survivors to the east. Saalman was able to observe the Japanese

landing area where he watched three Japanese tanks climbing off the beach.

|

|

|

Tanks |

|

Japanese tanks and infantry on Corregidor after the surrender. Note the

captured U.S. M-3 tank on the left of the photograph.

Photograph courtesy

of Dr. Diosdado M. Yap

Beach defenses after the surrender of Corregidor. Note the captured

defenders standing in the trenchline.

National Archives

photograph |

The Japanese landed three tanks, two Type 97 tanks and a

captured M-3. Two other tanks were lost 50 yards offshore while landing with the

2d Battalion, 61st Infantry. The surviving tanks were stranded on the

beach due to the steep cliffs and beach debris and were left behind by the

advancing infantry. In one hour, the tank crews and engineers worked a path off

the beach. When the tanks reached the cliffs, they found the inclines too steep

and were unable to move further. The Marines were alerted to the presence of the

tanks and Gunner Ferrell went to Cavalry Point to investigate the rumors of

tanks, and found the vehicles apparently hopelessly stalled.

At daylight the Japanese were able to cut a road to Cavalry

Beach but were still prevented from moving inland by the slope behind the beach.

Finally the captured M-3 negotiated the cliff and succeeded in towing the

remaining tanks up the cliff. By 0830, all three tanks were on the coastal road

and moved cautiously inland. At 0900, Gunnery Sergeant Mercurio reported to

Malinta Tunnel the presence of enemy armor.

At 1000 Marines on the north beaches watched as the Japanese

began an attack with their tanks, which moved in concert with light artillery

support. Private First Class Silas K. Barnes fired on the tanks with his machine

gun to no effect. He watched helplessly as they began to take out the American

positions. He remembered the Japanese tanks' guns "looked like mirrors flashing

where they were going out and wiping out pockets of resistance where the Marines

were." The Marines still had nothing in operation heavier than automatic rifles

to deal with the enemy tanks. Word of the enemy armor caused initial panic, but

the remaining Marine, Navy and Army officers soon halted the confusion.

One of the Marines' main problems was the steady accumulation

of wounded men who could not be evacuated. Only four corps men were available to

help them. No one in the battalion had first aid packets, or even a tourniquet.

The walking wounded tried to get to the rear, but Japanese artillery prevented

any move to Malinta Tunnel. No one could be spared from the line to take the

wounded to the rear. At 1030 the pressure from the Japanese lines was too great

and men began to filter back from the firing line. Major Williams personally

tried to halt the men but to little avail. The tanks moved along the North Road

with Colonel Sato personally pointing out the Marine positions. The tanks fired

on Marine positions knocking them out one by one. At last Williams ordered his

men to withdraw to prepared positions just short of Malinta Hill.

With the withdrawal of the 4th and 1st Battalions, the

Japanese sent up a green flare as a signal to the Bataan artillery which

redoubled its fire, and all organization of the two battalions ceased. Men made

their way to the rear in small groups and began to fill the concrete trenches at

Malinta Hill. The Japanese guns swept the area from the hill to Battery Denver

and then back again several times. In 30 minutes only 150 men were left to hold

the line.

The Japanese had followed the retreat aggressively and were

within 300 yards of the line with tanks moving around the American right flank.

Lieutenant Colonel Beecher moved outside the tunnel, shepherding his men back to

Malinta hill. He knew his men would be thirsty and hungry and ordered Sergeant

Louis Duncan to "See what you can do about it." Duncan broke open the large Army

refrigerators near the entrance to Malinta Tunnel, and soon was issuing ice-cold

cans of peaches and buttermilk to the exhausted Marines.

At 1130 Major Williams returned to the tunnel and reported

directly to Colonel Howard that his men could hold no longer. He asked for

reinforcements and antitank weapons. Colonel Howard replied that General

Wainwright had decided to surrender at 1200. Wainwright agonized over his

decision and later wrote, "It was the terror vested in a tank that was the

deciding factor. I thought of the havoc that even one of these beasts could

wreak if it nosed into the tunnel." Williams was ordered to hold the Japanese

until noon when a surrender party arrived.

At 1200 the white flag came out of the tunnel and Williams

ordered his men to withdraw to the tunnel and turn in their weapons. The end had

come for the 4th Marines. Colonel Curtis ordered Captain Robert B. Moore to burn

the 4th Marines Regimental colors. Captain Moore took the colors in hand and

left the headquarters. On return, with tears in his eyes, he reported that the

burning had been carried out. Colonel Howard placed his face into his hands and

wept, saying, "My God, and I had to be the first Marine officer ever to

surrender a regiment."

The news of the surrender was particularly difficult for the

men of the 2d and 3d Battalions who were ready to repel any renewed Japanese

landing. Private First Class Ernest J. Bales first learned of the surrender when

a runner arrived at his gun position at James Ravine, who announced, "We're

throwing in the towel, destroy all guns." Bales and his comrades found the news

incredible, "hard to take ... couldn't believe it." One Marine tried to shoot

the messenger but was wrestled to the ground.

Private First Class Ben L. Lohman of 2d Battalion destroyed

his automatic rifle, but "we didn't know what the hell was going on, as Japanese

artillery continued to pound Corregidor long after the surrender. "The word was

passed," recalled Lohman, "go into Malinta Tunnel." The men packed up their few

belongings and marched toward the Japanese. Three Marines of 3d Battalion

refused to surrender and boarded a small boat and made their escape out into the

bay.

Sergeant Milton A. Englin commanded a platoon in the final

defensive line outside Malinta Tunnel, and was prepared to deal with the

Japanese tanks with armor-piercing rounds from his two 37mm guns. As he waited

for the Japanese, an Army runner came out of the tunnel, shouting, "You have to

surrender, and leave your guns intact." Englin yelled back, "No! No! Marines

don't surrender." The runner disappeared, but returned 15 minutes later, saying,

"You have to surrender, or you will be courtmartialled after all this is over

when we get back to the States." Englin obeyed the order, but destroyed his

weapons, instructing his men, "We aren't going to leave any guns behind for

Americans to be shot with." The 4th Marines, 1,487 survivors, many in tears,

destroyed their weapons and waited for the Japanese to come.

The defenders of Hooker Point were cut off from the rest of

the island and were the last to surrender. They had finished the Japanese

survivors of the 2d Battalion, 61st Infantry, in the daylight hours and

for the rest of the day faced little opposition. As evening approached, they

heard the firing on Corregidor diminish, and Forts Hughes and Drum fell silent.

First Lieutenant Ray G. Lawrence, USA, and his second in command Sergeant Wesley

C. Little of Company D, formed his men together at 1700, and marched to Kindley

Field under a bedsheet symbolizing a flag of truce. The Marines soon found

Japanese soldiers, who took their surrender.

Marine casualties in the defense of the Philippines totaled

72 killed in action, 17 dead of wounds, and 167 wounded in action. Worse than

the casualty levels caused by combat in the Philippines was the brutal treatment