|

Looking to see if there were any Japanese around I was surprised to see a group

of our men near the head of the runway playing baseball.

"What the hell kind of a war is

this?" my immediate thought was.

That thought applies as much today as it did that instant.

A combat jump into a baseball game!

I crawled sheepishly out from under the bomber and started walking toward

the guys playing ball. As I walked I heard the sound of motors.

Looking to determine where the sound

was coming from, I was elated to see amphibious tanks displaying American

markings. They were climbing out of the water and up onto the runway.

I did not learn until many years later that this amphibious outfit had made the

initial assault on the island and cleared the landing strip for our jump.

Our job was to purge the island of

the remaining Japanese. We assembled at the Southern end of the runway and, in

patrol formation, moved inland. I was scouting about 100 feet out in front of the company,

when I came upon a Native village. I cautiously moved to a vantage

position.

Looking into the village, I could see three of what appeared to me to be

Japanese soldiers, standing in a line with their hands behind them, apparently

tied to a post. I moved quickly into the open, where I was exposed and

then back to cover to see if I could draw fire. After a few exposures with

no one shooting at me, I went into the village and approached the group tied to

the posts.

As I walked up to them I could see they had their hands tied behind them around

the post and that their anklebones had been hewed off on the outer part of each

leg, probably by a sword. They were the enemy and I felt no sorrow. The medics

came in and undertook the job of removing these maimed men.

I learned later that these men were from Formosa (Taiwan).

The Japanese had used them as labor troops. They had been disabled to

prevent them from working for us.

We proceeded some distance across the

Island to a second airstrip which the Japanese had abandoned completely. Here we

dug in for the night. My foxhole was located at the south-end of the

runway, directly next to the road which connected the two airstrips. The night

passed uneventfully.

In the morning, my platoon went out

on patrol. We covered an area of about 5 miles before we turned and started back

toward our positions.

I was about 50 yards in front of the second scout, following a trail

going up hill. As I reached a point that allowed me to see across the

crest of the hill, I spotted a patrol of Japanese soldiers, coming my way. They

were about one hundred and fifty yards in front of me and slightly to my right.

I dropped down, gave the signal "Enemy In Sight" to the second scout, then

arose, fully prepared to start shooting.

To my surprise, I realized that they

had seen me too and had taken flight down a trail to our right. Spinning, I

motioned for the platoon to move to the right, while I took chase through the

dense undergrowth. As I broke onto the trail taken by the Japanese, I moved

through the platoon to take the lead position. One of our men pointed to

blood on the ground

and I moved out quickly following the blood trail. It turned left

and went up a small embankment. There, I saw the Japanese soldier. He was

sitting up, drinking from his canteen. Seeing me, he whipped his left arm behind

his back and threw himself flat on the ground. I dropped to the ground,

expecting a grenade to go off. After about 10 seconds, I took another peek, his

left arm was still under his back and his canteen was lying on his chest

spilling water. I was sure he had a grenade. Not wanting to use my Thompson

machine gun, I borrowed a rifle from the trooper closest to me and shot the

soldier through the head. The shot did not kill him outright; he was opening and

closing his mouth, but my second shot came out the top of his helmet.

Hearing the shooting, another patrol arrived and a lieutenant rolled the soldier

over and commented to those of us who could see, �Look at this.�

The Japanese soldier still had a concussion grenade in his hand with the

detonator pointed toward the ground.

During our patrol actions, we took a few Japanese as prisoners but we rounded up

quite a lot of Formosans. They were caged in a makeshift enclosure of barbed

wire. Our cooks, who had little to do while we were out on patrols, spent their

time teaching all the prisoners English. After several weeks teaching, we

were surprised when, coming in from a patrol, we passed the compound housing the

Japanese. Someone shouted "Tojo."

Quickly, all the prisoners responded in unison bowing and shouting "Son

of a Bitch."

What sort of a war indeed!

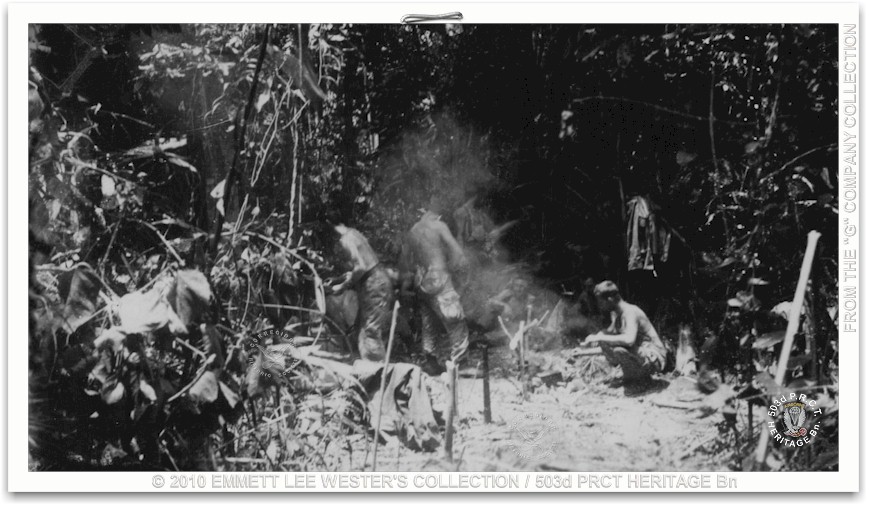

Drying Out -

getting dry was a battle in itself, what with the almost daily rainfall. We

would set a fire and attempt to dry ourselves.

A kitchen was set up and we started

getting hot meals. With little happening around our perimeter, several of us

decided to go to the beach and try some hand-grenade fishing. Wearing

nothing but undershorts and boots, we proceeded to the coast � a distance of

only a few hundred yards. Moving down the beach, we came upon some chickens.

Well, this was much better than fish,

so we proceeded to shoot as many as possible.

I had only one clip of ammo for the Tommy gun and I had no idea of

how many rounds I had fired getting chickens. While the other men picked up the

chickens, I moved further down the beach to a point where a large boulder

projected out over the waters edge. To get by it, I had to stoop. As I

passed under the boulder and moved further down the beach, I came upon two

Native huts.

Moving to the rear of these huts, I surprised two Japanese soldiers who

were sitting on the ground and eating the hearts of "palm trees." I stopped,

raised my Tommy gun and shouted, "Hold it, you sons of bitches!"

The soldier farthest from me dove around the corner of the hut, with his gun in

his hand. As I turned to see that he was not coming around to get to me, the

other soldier jumped and ran down the beach. I dashed out after them, brought

the Tommy gun up to my shoulder, and shouted, "I'll cut you bastards in half!" I

squeezed the trigger. One round fired, and that was a miss. I had spent all my

ammo on chickens!

The other men heard the shot and came running, but they only glimpsed the two

Japanese soldiers as they disappeared into cover. (Many years later, at the 503d

reunion, they would kid me about standing there on the beach, with my Thompson

up to my shoulder, shouting, "Bang, bang, bang!" at the Japanese running away

from me. Some things are harder to live down than others.)

Finding the area around the airstrip

clear of Japanese and chickens, we started pushing across the island, following

paths made by either the Japanese or the Natives. On one occasion I was

following a path that I was sure was made by the Japanese.

I drew this conclusion because the path had vines fastened to trees and

draped along one side. Natives did not need this to move in the dark.

As I rounded a turn, a sniper fired at me � putting a hole in my right

sleeve, just below the shoulder. I hit the ground instantly, quickly

rolling to my right. He fired a

second shot which missed me completely.

However, that shot gave me his position:

he was in a tree about 300 feet in front of me, totally exposed. I sighted across the sights on the Tommy gun and hit him with

a burst of three rounds.

Thinking about this later, as I

often did,

I will never know how he missed his opportunity to get me.

My best guess is that I surprised him before he�d reached his firing

position in the tree.

Because of the strain involved,

scouts were rotated at short intervals.

I do not remember the name of the scout who led the second platoon, but

it was he who relieved me. Within three minutes after taking the lead, he was

hit by a burst from a machine gun. The Japanese had dug in on a coral hill and

were waiting for us. We took whatever cover we could find, moved into firing

positions, and battled throughout the day and into the night. Daylight came and

we put feelers out to see if the Japanese were still there. They had moved out

and the scouts body was gone.

We moved up the hill into the

evacuated Japanese positions. There, we found

him. His body had been

carved as though he were a mere piece of beef. All the flesh was gone from

his legs, arms, buttocks and chest and his heart and kidneys were missing.

We had no doubt that they were eating our dead.

No prisoners, we vowed to ourselves.

Continuing on, we hit the Japanese

again. This time we saw them before they saw us. A fire-fight started and we set

up 60 mm mortars to blast them out of their positions. Suddenly, a man near the

mortar positions was hit by a sniper hidden in a tree.

The sniper was smart, only firing when there was a lot of shooting going on

along the front line.

Although we pinpointed the tree he was hiding in, we could not see him,

even when we were directly under the tree. Suddenly, whether by accident or

design, I don�t know to this day,

one of the mortar rounds fell short and exploded in the top of the tree.

Down came the sniper, tumbling to the ground amid the hoops of our joy.

After having served upfront for some time,

my squad earned the good fortune to

be sent to the rear in order to rest.

We were milling around, listening to the sounds of 25�s and 30�s going off.

Suddenly, a bullet missed my right ear by a fraction of an inch! Damn! I

hit the ground face down beside a trooper who had already taken cover, my ear

ringing loudly. Just when I was happy I was hidden from the sniper,

another bullet hit the ground between us.

The trooper next to me jumped up and ran around in three small circles, and then

dropped back into his original position.

I still chuckle at his confusion.

That second shot was the snipers

undoing. From my prone position,

I found

I was looking straight at him. He was in a large tree, which I judged to

be about 300 yards out. He had built a platform in the tree and he too was

laying prone. So my target was his

helmet, which I could see shifting back and forth as he looked for another

target. It was the sight of his

helmet, 300 yards out, that brought

back the memory of another shot that had brought me confidence in what I needed

to do.

As I looked at my target, I recalled

a time not so long ago when my Australian friend, Berto Poppi and I were in the

Australian bush.

On that occasion I had fired a shot from a .45 pistol into a large tree.

Berto asked me, challenge like with his .22 in hand,

if I thought I could hit the hole that the .45 slug had made.

Taking his .22, I drew a tight sight on the hole and hit it dead center.

It appeared to me the helmet was

about the same size as the hole made by the .45.

My Thompson submachine gun would be ineffective at this range, so

I borrowed a rifle from the trooper next to me, Beuford Adams.

I zeroed in and commented, "This one's for Berto." I took a tight bead on

the target and squeezed off a shot. I saw a flash as the bullet hit. The

sniper's rifle fell to the ground and his head shifted to my right. I squeezed

off another shot. Again, I saw a flash on the Japanese helmet.

Buford turned to me and asked, "Who

the hell is Berto?" I don't remember ever answering him, but asked him "What

kind of ammo do you have in your gun?" He replied, "Blue Goose."

So that explained the flashes I saw when my bullets hit their

target. (Blue Goose is the name given to the .30 caliber explosive ammunition

used in aircraft machine guns.)

A few of the men had started using

Blue Goose after we confirmed that the Japanese were turning their .25 caliber

slugs around for ambush fighting to make them tumble in flight. When one of

their bullets hit a man, it tore an awful hole.

The fighting continued throughout the

day. The people back at the airstrip tried to deliver K-rations to us,

using an artillery spotter plane. The pilot would fly over our lines and drop

crates of food. Unfortunately, most of the crates hit the Japanese positions.

The most any of us received was one tenth of a box of K-ration. This amounted to

one can of meat, or bacon and eggs, per squad.

We spent the night without incident.

When morning came the word came to move forward. As the lead scout, I

moved the platoon to a position atop a hill. We were roughly 500 yards from the

Japanese positions,

who were dug in on a coral, jungle-covered hill. The terrain we were

approaching through was 6-foot high Kunai grass, sloping downhill toward the

base of the hill occupied by the Japanese. To keep from exposing ourselves, we

crept down the hill on our bellies.

When we were about halfway to the Japanese positions, the Seabees started firing

their 75mm howitzers. The first shell came through the Kunai grass, so close to

me that I could feel its heat and the noise was unlike anything I had ever heard

before. It scared me so badly that I became shaky. The shell exploded at

the base of the hill, about 300 feet in front of me.

I do not remember how many shells were fired before word was radioed back

to cease fire, but none of the others were as close to me as that first one. I

learned later that the howitzers were firing at maximum range (11 miles) and

could not quite reach the Japanese positions. Their falling trajectory took them

through the Kunai grass and into the base of the hill we were attacking.

Moving down to the base of the hill directly in front of the Japanese,

we took advantage of the jungle to regroup for the final assault. Our topkick

came over to ask me to lead the assault. Seeing my state of terror, he turned to

the second scout and told him to take over. (I did not argue the point). Unaware

of my experience with the shell, he probably thought I was developing battle

fatigue. Whatever the case, he told me to hold my position until the last man in

the squad had entered the jungle.

The squad passed by me, until the last man was about to get up and go. There

were sounds of Japanese 25�s going off and the bolts on their rifles slamming

shut as they reloaded. Suddenly, our men panicked. They came running out of the

jungle as though they were being chased by the devil himself.

As the next to the last man emerged, he turned and fired his M-1 point

blank at what he thought was a Japanese soldier chasing him.

As it turned out, the man

immediately behind him was a member of our squad. I have no idea how that shot

missed. I can only think it was an

act of God.

Having

failed to take the hill, we pulled back to the positions we had held when we

initially engaged these troops. Taking firing positions, we waited for the hot

food we had been told was being delivered to us. It was to be brought by our

company cooks, armed and leading a group of Native carriers. We waited, but they

never arrived. We later learned that they had been fired upon by a sniper. That

was enough for our brave �cook in command�. Though no one had been hit, they

proceeded to bury our food where they stood and returned to base camp.

Much later in the war, the leader of

this failed food train was awarded the Silver Star for his actions. His award

was accompanied by the hisses and boos from the regiment.

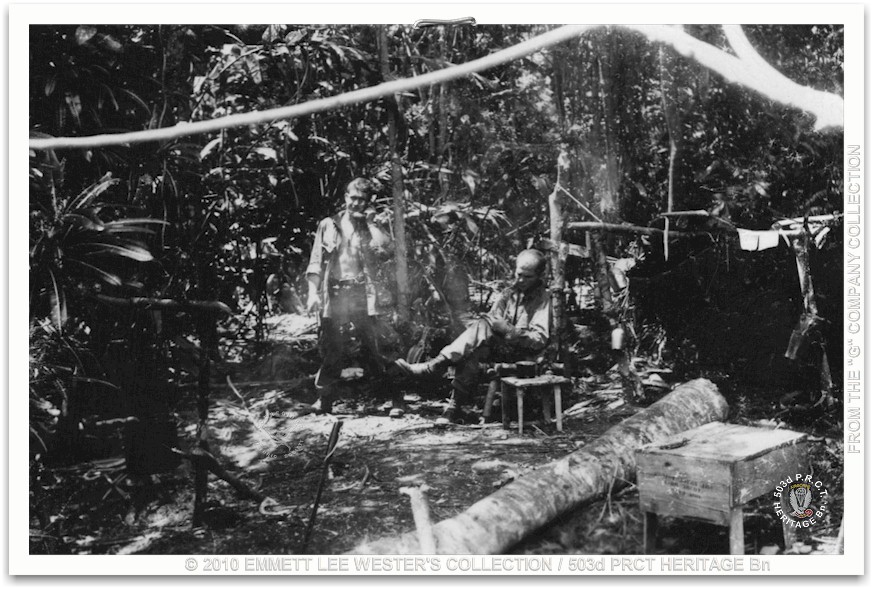

A jungle CP could be any shady area where

there was a field telephone, a bench and a table or two. Lt. Smith sits.

The following morning I received one of the most dreaded orders I was ever

given. I was told to take two men and to cut a trail to our left, making as much

noise as possible. We were the bait

to draw fire from the Japanese, to test whether they had moved in that direction

during the night.

I could only think that this was the

punishment for my failure the day before.

We journeyed out about 200 yards, hacking and banging on rocks and trees. Each

minute was my last minute on Earth, but nothing happened. We were ordered back.

Rejoining the squad, we moved

cautiously forward into and through the Japanese positions of the day before.

Initially moving with caution, we met the unmistakably awful odor of rotting

flesh. We hurried to get away from

the stench. Our route took us out of the rain forest and into an open area where

the trail followed a ridge. Walking single file, we pressed forward.

A grenade exploded approximately 300 feet ahead of us. Moving forward to the

point of the explosion, we found a Japanese soldier with his guts blown out,

lying between the fin roots of a large tree. We shrugged it off, assuming he was

chicken and took the easy way out.

What sort of fear makes using your own grenade the easy way to die?

It troubled me.

Within a mile further down the trail,

the same thing happened again: another grenade explosion for no apparent reason,

another dismembered Japanese body.

Someone in our group changed our minds.

Our assumptions of these men

taking the easy way out was all wrong. They were actually death outposts. Each

explosion of a Japanese hand grenade was a message to the main force, letting

them know exactly where we were. The soldiers who were sacrificed apparently

were too sick to keep up with the main body of troops.

Faced with this conclusion, our

tactics became cut-throat - literally.

We would watch the trail ahead for anything large enough to hide a

Japanese soldier. Then we would send a man around to the flank. If he spotted

one, he would slip up on him, taking him from the rear with a knife, before he

had time to detonate the grenade.

When I had completed my time out

front, I was relieved and placed next to Andy Pacella, the last man in the

squad. Andy was the second scout. We were moving through fairly open country,

along the base of a hill, when Andy fired. Turning to see what he was shooting

at, I saw a Japanese soldier starting to bend forward. He fired a second

shot and the Japanese fell to the ground, face forward with his knees

pulled up against his chest . He was gasping for breath. I walked over to him,

pulled my .38 revolver from its holster and put one shot through the top of his

head. This stopped his suffering. Then, grabbing his feet, I straightened him

out on his stomach, crossed his legs and rolled him over for inspection. The

lieutenant in charge of the patrol came over and commented, "Just like shooting

hogs." I thought to myself, "Oh no, hogs don't kill and eat humans."

The Japanese still caused us some

very unpleasant surprises. Continuing on, we came into a large grassy area that was

sparsely covered by trees. To the right, in the distance, we could see the

ocean. Our patrol moved south, parallel to the shoreline. Suddenly,

there was a yell, and three quick shots.

One of our men had stepped into a foxhole with a Japanese soldier still

occupying it! He recovered his footing as though he had been shot out of

the hole by a slingshot, firing the shots point blank into the Japanese soldier. He sat down, wiping his forehead. The position he had stepped

directly into was a trap-door sniper's hole.

Generally,

sniper's holes were just deep enough to kneel in and covered with a

camouflage lid which was made from small tree limbs and grass. This would

allow them to rise up, pick a target, shoot and disappear from sight. We gave

them the name "Trap-door Snipers." With the threat of snipers hiding in the

grass around us, the order was given to spread out shoulder to shoulder and to

advance across the area. I do not recall that we uncovered any more

snipers.

Reaching the jungle again, I was

placed out front to lead the way. My route took me through a swamp area with

large mango trees whose roots protruded into the water. Suddenly, there

were loud clanking noises. My first thought, illogical as it could possibly be

was "Tanks!"

I hit the ground and waited.

The noise stopped as fast as it had

started.

Rising from the ground where I had

dropped when I heard the first clank, I moved slowly forward. Roughly

twenty feet to my right, in about four feet of water, were giant clams. They had

been washed into the Mangrove swamp and were responsible for the noise.

Apparently, they would slam their shells shut whenever they detected motion.

As I moved on, this was confirmed: as I passed more open clams, I saw them

clanking shut.

Having moved through the swamp area, the company followed the trail as it

turned inland. At this point, I was relieved and my squad was moved to the

rear.

Following the trail we came to a fresh water spring. The water flowed from the

ground into a pool, roughly 30 feet by 50 feet in size. Lying in the pool

was a badly decomposed Japanese body. There were strings of decay extending

toward the surface of the pool from his body.

We had been told that this was the only fresh water on the Island and our

�floater� was it�s last Japanese guardian.

We filled our canteens

gingerly, careful not to stir up the crud and thereby further contaminate the

contaminated water.

In this location, we dug foxholes and cut fire lanes toward the pool. One

trooper flushed out one of the enemy while cutting his fire lane. The Jap

soldier came running toward us with the trooper chasing him and swinging his

machete. The trooper caught up to the fleeing Japanese soldier, swung his

machete, and decapitated him. The corpse's head fell onto his left shoulder, as

the body fell to the ground.

With our foxholes dug and our fire lanes cut, we started booby-trapping the area

around the water hole. We set hand grenades in strategic places around the pool.

I modified one grenade by pouring it almost full of powder and arming it with a

"myrtle switch" - an instantaneous detonator.

Next I tied a wire to the ring and ran the wire to my foxhole, where a

pull on the wire would set off the grenade. In the middle of my fire lane,

about 100 feet from the pool, there was a tree with a diameter of about three feet.

I placed the grenade in the fork of the tree, about four-foot off the

ground. With everything in place, we settled in for the night. Three men

occupied each foxhole.

During

the night, while the man on my right was on watch, a large snake made its way

across our foxhole. It passed across my chest and across the legs of the

man on watch. The snake appeared to be about 20 ft long. It passed over us and

went on about its business, but it took about 30 seconds for the man on watch to

get over his fright. He kept hitting me on the chest and repeating over and

over, "Did you see that?" "Did you see that!"

To keep him from exposing our position to any Japanese that might be nearby, I

sat up and placed my hand across his mouth. Later that night, hand

grenades did start popping.

Detonators were going off, but the hand grenades were duds. Suddenly, I saw a

form pass from my right and toward the tree in which I had placed the grenade.

I pulled the wire, exploding the grenade. For the rest of the night, there was

no more activity.

The following morning, we went out to

pick up the unexploded booby traps. While doing this our BAR gunner came upon a

Japanese soldier. He was sitting in the bush with his left hand blown off. A

short burst from the BAR finished him off.

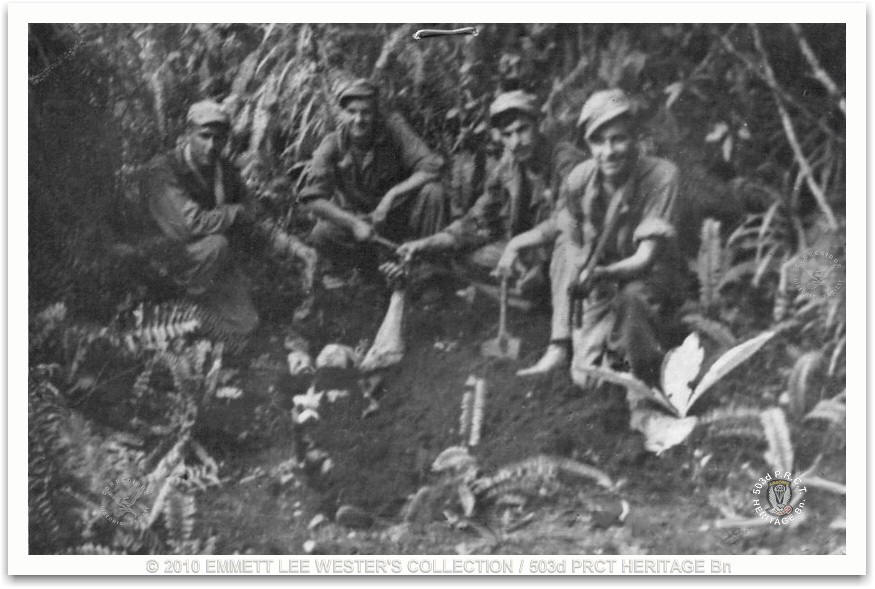

A

makeshift burial - and a warning to the enemy that we were retaking the jungle

one trail at a time.

We did bury the enemy dead whenever

we could, but as a tactic to make the Japanese fear us, it was common

practice to bury the dead enemy with one arm remaining above ground. This

allowed the wild dogs on the island to consume the body. Sometimes we did take a

few prisoners, but we had no way to take them with us. So someone devised a

holding technique, which we called the Indian Death Lock, to hold the enemy

prisoners until we returned � if we returned. We would find a tree approximately

6 to 8 inches in diameter, slide the prisoner up the tree, with his arms tied

around the tree. Then, crossing his legs around the tree, we would force his

left foot inside and over his right knee. Using his Japanese belt of a

thousand stitches as a hangman's noose we would fasten it around his neck with a

slip knot and tie the other end higher up to the tree trunk. As long as the

prisoner had strength in his legs and arms, he could hang on. If his strength

gave out, he was choked to death. I only knew of this happening once.

Although we had little to eat, things became more relaxed. We felt relieved that

there had been no enemy soldiers found by the patrols that had been sent out to

check the area around the perimeter. We members of G Company got together to

consolidate whatever food we had,

but found it was very little. However, one man had been saving some coffee. This

was the treat of all treats. Immediately, we set out to gather

firewood. One of our men wandered out into the bush to gather wood.

A young Indian, whom we had nicknamed Chief, had just joined the outfit as a

replacement. He swore he could smell a Japanese soldier. Hearing the noise the

gatherer was making and thinking it was a Japanese, Chief fired a burst from his

Tommy gun in that direction. Our man, 'Punchy' Crosier, was hit in the

hand, the leg, and had a chunk cut out of his penis.

He came charging out of the bush, cussing a blue streak. One of the only

printable curses, and only barely so, involved him taking an oath �to kill

that effing Indian if lose one inch of my

cock!�

Meanwhile, the Lieutenant had gone to

the water hole to shave and clean up. Filling his helmet with water, he stepped

up on the bank and applied soap to his face. Then, with a small mirror, he

prepared to shave. Suddenly, in the mirror he saw a Japanese sniper, in

the top of a palm tree on the far side of the pool. He threw the mirror to the

ground and came running toward us, shouting, "Jap! Jap!" The first man to reach

him had a carbine and handed it to the lieutenant, who grabbed it and cautiously

moved back toward the waterhole. Raising the carbine to his shoulder, he

fired at the top of a large coconut palm directly across the water hole. On the

lieutenant's second shot, the Japanese soldier dropped his rifle, sat erect and

raised his hands. The lieutenant fired a third shot, but it, too, missed the

mark. Beuford Adams was standing beside the lieutenant. He was

annoyed by the officer's marksmanship. He raised his M-1 and hit the Japanese at

about the third button on his uniform, killing him instantly. His body

came out of the tree, spread eagle and fell into the water hole , completely

contaminating it by stirring up the decay from the rotting body that still lay

in the pool.

Things quieted down and a fire was

lit and we started making our coffee. One of the men who had been gathering the

wood came in with a sock nearly full of rice. He poured it into a helmet, poured

water over it, stirred it a few times, poured the water off, and added new

water. Then he placed the helmet with the rice and water over the fire. We all

ate the rice. After finishing we asked him where he found the rice. He pointed

to the beheaded Japanese corpse and said, "From him. That's why I had to wash

it; there was blood in it."

To this day, I cannot eat rice �

especially if it has tomato sauce on it.

After we had eaten what little we

had, we milled around, looking at the vegetation and the wild birds. I had

nothing in particular to do, so I wandered to the rear of my position. Against

the rising slope of a hill, I found a small cave that appeared to have been man

made. Thinking that it might have Japanese stores in it, I proceeded to

enter. The cave was only about ten feet deep and terminated against a ledge.

Sliding my hand along the shelf portion of the ledge, I could feel loose, soft

earth. I immediately started

digging. To my surprise, I uncovered a dish that resembled a serving dish we

would use at home. With the dish in my hand to show off, I came out of the

cave. The minute I emerged, a native man of the island came toward me,

indicating by hand signs that it belonged to him. I had no desire to upset

the natives, so I gave it to him and, by handsigns, promised to leave the cave

and its contents alone. I am still amazed that the native could hide that

close to our position without being discovered and wonder how many of our

episodes were witnessed by these unseen eyes.

I learned later that the dinnerware I

had uncovered belonged to a Dutch Mission and that it had been hidden there to

keep it safe from the Japanese.

When we had cleared all the Japanese

from the area of the waterhole, we started our push to the end of the island. We

moved to the edge of the jungle, where we could look out over a beach with many

native buildings. These buildings were erected on poles, just off the beach in

shallow water. To the left of the village was a group of Japanese soldiers

with their backs to the ocean. We emerged from the Jungle ready for a fight, but

the Japanese, rather than firing at us, came charging with fixed bayonets and

swords. It was a turkey shoot. None of the Japanese survived.

After we had stopped shooting and

were milling around on the beach, I noticed the population of the village, men,

women and little children, emerging from the water. They had waded out until

only their noses were above the water and had waited there until the conflict

was over.

With the Japanese resistance totally

broken, we dug in around the village. I took this opportunity to take off

my boots and wash my socks. This was the first time my boots had been

removed since we started our push across the island, over a month earlier.

That night, I slept with my boots off and my socks spread out on the sand to

dry. When morning came, my boots and socks were gone. They were nowhere in

sight. Not only were my boots and socks gone, but anything left laying around

had disappeared. Looking around, we saw boots randomly scattered around the

sand. Once we picked them up, we had our answer.

We could see that each had been pulled to a hole in the sand, but that

the boots were too big to go down the hole. Large land crabs, roaming during the

night, had tried to steal them. We dug down in the sand and soon had recovered

our missing articles.

After eating a banana and coconut breakfast, I decided to go fishing.

Another trooper, Getchel, decided to go along. Two very cooperative natives

supplied an outrigger. We set out with the two natives paddling. About a

half mile off-shore, the native in the front of the boat started shouting and

pointing to the water under the boat. Both natives back paddled to stop

our forward motion. The native in the rear grabbed a small stone hatchet and

went over the side.

I watched as he moved to a hole in the coral. There, he began chopping away at

the coral. Then, rising to the boat, he took a stiff wire with a ring bent on

one end, slipped it on his finger and dove back to the hole he had been chopping

on. A cloud of black fluid arose from the hole and obscured my view of the

diver. Seconds later, he popped to the surface holding a large octopus, which he

handed up to me. I grabbed the tentacles and pulled to get it into the

boat, but other tentacles were attached to the hull. I used all my

strength, but I could not break it loose.

Our diver got into the boat, reached over the side and pulled the tentacles

loose from their other end. With the octopus on board, our diver took his

hatchet and cut off a section of tentacle. He handed it to me saying, "Bagoose,

bagoose." I pushed it away. So he offered it to Getchel, who also

refused it. Then he passed it to the native in front, who gladly took it

and started chewing on it. Looking back at me with a broad grin which

exposed his blackened teeth, he repeated, "Bagoose, bagoose," and quickly

consumed the whole chunk. Having enjoyed their treat, the natives started

paddling out to sea.

As they paddled further out, I began to worry. We were no longer within

swimming distance of the island. In fact, when I looked back toward the

island, I could only make out a dull haze where the island should be.

Well, they finally stopped paddling and both men slid into the water. Swimming

with their heads under water, they could determine the greatest population of

fish. They would then point out that area and swim clear of the area. We would

toss grenades at the spot they had indicated. After the grenades exploded,

they would take the stiff wire they carried, dive down, and string fish on the

wire. When their wire was loaded, they would come to the outrigger, where we

sat.

As they unloaded the fish we would keep them spread evenly inside the

hull. When the boat was fully loaded, its hull rose only about two inches above

the water.

One of the natives brought a Japanese rifle up from the bottom. At the

same time, Getch thought he could see a pistol on the bottom, and he

stripped down to his shorts and went overboard. Seconds later, he came to the

surface with a nose bleed. The water was too deep. He climbed back

into the boat, commenting that the natives had no trouble at all reaching the

bottom. In all, the natives brought up two rifles and the pistol, which my

companion took as a souvenir.

On the next dive, one of the natives

brought up a shelter half tied around about a bushel of yams. When he added that

to our load, our buoyancy changed drastically. Now there was less than one inch

of hull above water. Seconds later, the other Native emerged with another

shelter half of yams. When he placed them in the boat, we went under. Fish

were floating all around the outrigger. I could only think that the sharks

would have to come for this feast.

Hanging onto the submerged hull, I

looked for some reaction from the natives. After all, they knew more about the

waters we were in than I did. The more active of the pair started swimming

out to sea. I watched in amazement as he swam further and further away.

After swimming about three hundred yards, he stood up. The water was only about

four-foot deep. Heaving a sigh of relief, we swam the outrigger out to

where he stood. Together we picked it up, dumped the water, and got back

aboard. The natives stored the yams on the coral reef to pick up

after they delivered my companion and me ashore. We paddled back to where the

fish were floating and picked up all we could find. Then we headed for shore.

That evening, we had a great fish bake over open fires on the beach.

At the time I was not aware that the two natives paddled back to the spot where

we had picked up the Japanese supplies and dove for the remaining items which

they had found lying on the bottom. One of the items they found was a chrome

fingernail clipper. Finally, the native brought it to me, indicating that he did

not know what it was. I held out my hand to take it so I could show him how to

use it, but he was reluctant to let me have it. After I promised him that

I would give it back, he let me have it. I slowly moved the press lever

into the clipping position and demonstrated its action by clipping my nails.

The Native was all smiles and anxious to try it on his nails. I returned

the clipper to him and watched as he clipped one of his nails. Then, satisfied

he could use it, I left.

Later that day, I observed him in a group laughing and appearing to be mystified

about the actions of the native sitting in the middle of the group. When I

wandered over to them, I saw the native with the clipper clipping his nails and

causing the blood to flow over the ends of his fingers. Seeing this I held out

my hand for the nail clipper. Knowing I would not keep it, he placed it in

my hand. Then I took his hand in mine. I indicated a no-no toward his

fingers, letting him know he had cut too much. He seemed to grasp my

meaning. The following day, the Native with the clipper came to me all

smiles and glowing with pride. He wanted to show me how he could clip hairs from

his face. Apparently, the clipper was a better tool than the clam shells they

were using to pull the hair from their faces.

With our mission completed, we packed up and returned to an area overlooking the

airstrip where we had made our initial landing. As a quick way to get us

settled, we were given hammocks to hang between trees. I slept soundly.

In the morning, we were told to take down the hammocks and erect tents. One of

the hammocks we took down hung on our outer perimeter. It belonged to a man who

had been evacuated to the hospital. He had left all his gear in the

hammock. That hammock had been knifed and slashed. Apparently, a die-hard

Japanese thought the man's barracks bag was a person.

Since we had no assigned duties, we spent our days getting our equipment

in order, playing cards or just sitting around having bull sessions.

My time was usually spent sitting on the high ground along the airstrip and

watching the P-40's come in and take off. They appeared to be dancing as they

bounced down the strip. On one occasion, a Beechcraft 12 seater came in

and as its wheels hit the runway, it veered left and hit the embankment.

It immediately burst into flames.

No one got out. Since it was not a military aircraft,

I have often wondered who was on that plane.

On about the third or fourth night

back at the airstrip, we were surprised by an air attack. We had an open view

across the runway and the open sea. So, we were in an ideal spot to watch the

action. A single plane came in and anti-aircraft fire opened up from the

ships lying off-shore and from the guns on-shore. The tracers made a fiery

umbrella as they crossed each others path at the peak of their arcs. The

plane could be seen quite clearly, being lit up by the exploding shells.

To my amazement, that plane continued on course and dropped its bomb squarely

atop the Japanese fuel dump. They had to abandon that fuel dump when we took the

island with our own air attack.

My last memory of Noemfoor is one that I cherish even today. It is the memory of

hearing 'Ave Maria' played on the loud speakers just after lights out.

|