|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

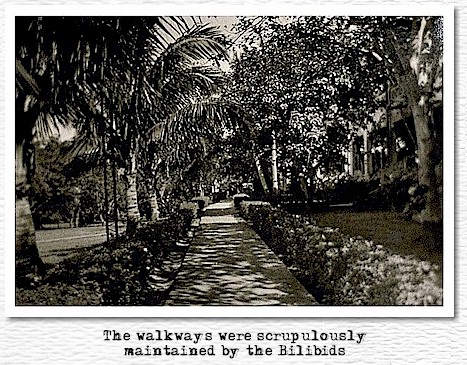

There is more to Corregidor than being the site of the defeat and surrender of America’s forces in the Philippines, and the devastating battle to retake it three years later. It symbolizes war’s duality - destruction and creativity, brutality and comradeship, inhumanity and humanity, yes. But before all of this, before World War II, it was an idyllic place for the Army families who lived there. This is the pictorial story of that other

part 1

Corregidor

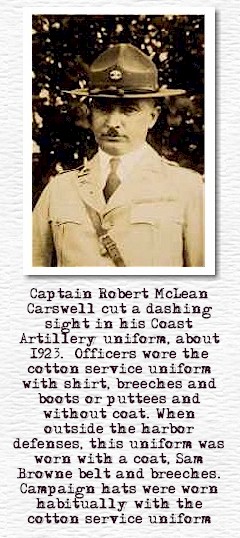

entered our family’s life in 1923, when my grandfather, Captain Robert

M. Carswell, was first stationed there, commanding B Battery of

the 59th Coast Artillery. He had been a civil engineer and

lawyer in his home town of Wilmington, Delaware. He also served in the

Delaware National Guard, and was called up for duty in the Mexican

Punitive Expedition against bandit Pancho Villa. Apparently the Army

offered more opportunity than civilian life, and he joined the regular

Army soon after.

Corregidor

entered our family’s life in 1923, when my grandfather, Captain Robert

M. Carswell, was first stationed there, commanding B Battery of

the 59th Coast Artillery. He had been a civil engineer and

lawyer in his home town of Wilmington, Delaware. He also served in the

Delaware National Guard, and was called up for duty in the Mexican

Punitive Expedition against bandit Pancho Villa. Apparently the Army

offered more opportunity than civilian life, and he joined the regular

Army soon after.  On

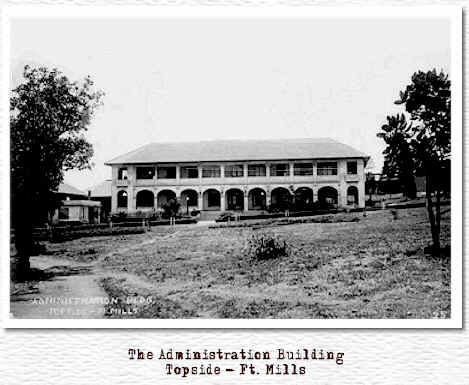

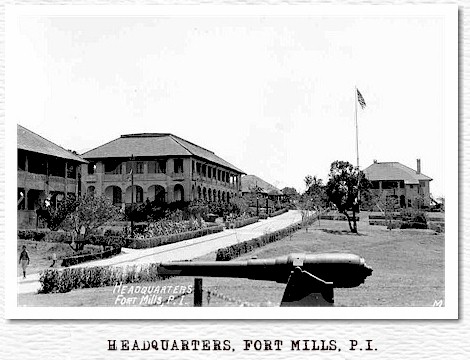

Corregidor, the family took up residence on Topside at lower quarters

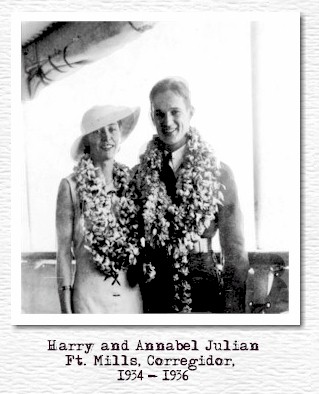

#23, right behind the famous flag pole. Their furniture didn’t, much to the unhappiness of my grandfather. Harry Julian was

assigned to the Guard Battalion, and they lived on Middleside. The Julians left Corregidor in 1936 with a new addition, their son Bob. Bob

was born at Sternberg General Hospital in Manila. There was a flu

epidemic on Corregidor at the time, and most of Corregidor’s hospital

staff were sick.

On

Corregidor, the family took up residence on Topside at lower quarters

#23, right behind the famous flag pole. Their furniture didn’t, much to the unhappiness of my grandfather. Harry Julian was

assigned to the Guard Battalion, and they lived on Middleside. The Julians left Corregidor in 1936 with a new addition, their son Bob. Bob

was born at Sternberg General Hospital in Manila. There was a flu

epidemic on Corregidor at the time, and most of Corregidor’s hospital

staff were sick.

My

dad was the son of poor Swedish immigrants to the Pittsburgh area. He

ran away from home and joined the Army, one of the few places where jobs

were easily available during America’s Great Depression.

He

was in the 1st Calvary in an armored car unit stationed in Texas.

He soon realized that it was better to be an officer than an

enlisted man. So he studied hard, took the examination for the US

Military Academy1

(USMA, West Point), and

scored first on the exam that year. He graduated in 1935 from West Point

with an excellent scholastic and athletic record.

His

first two posts were in the Coast Artillery at Ft. Story and Ft. Monroe

in Virginia. Posted to Corregidor, he was first in the 60th CA (AA) and

had his guns on the plain in front of the "Y." Someone within

the War Department must have had a wry sense of humour as his next

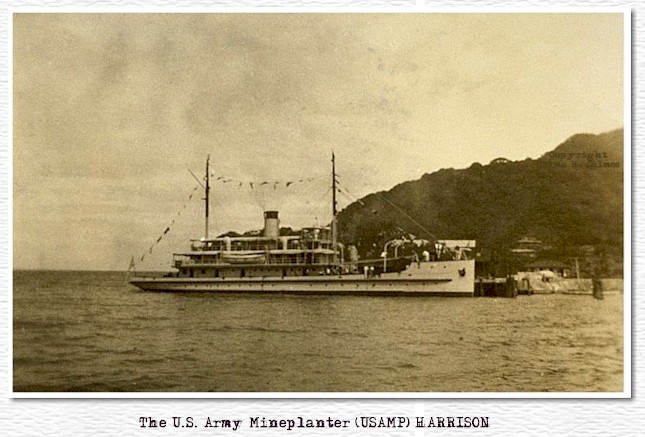

assignment on Corregidor was as commander of the US Army Mineplanter (USAMP) Harrison,

within the 59th CA. This was commissioned in 1919 and

was named for General George Harrison, the first American governor of

the Philippines. The mineplanter maintained the minefield in the North

Channel of Manila Bay (the Navy maintained the South Channel minefields,

from their base in Cavite), adding to the defenses of the much

better-known "big guns" of Corregidor. (More on the mineplanter and the minefields will come later.) It docked at the North

Dock, where the water taxis dock today.

My

dad was the son of poor Swedish immigrants to the Pittsburgh area. He

ran away from home and joined the Army, one of the few places where jobs

were easily available during America’s Great Depression.

He

was in the 1st Calvary in an armored car unit stationed in Texas.

He soon realized that it was better to be an officer than an

enlisted man. So he studied hard, took the examination for the US

Military Academy1

(USMA, West Point), and

scored first on the exam that year. He graduated in 1935 from West Point

with an excellent scholastic and athletic record.

His

first two posts were in the Coast Artillery at Ft. Story and Ft. Monroe

in Virginia. Posted to Corregidor, he was first in the 60th CA (AA) and

had his guns on the plain in front of the "Y." Someone within

the War Department must have had a wry sense of humour as his next

assignment on Corregidor was as commander of the US Army Mineplanter (USAMP) Harrison,

within the 59th CA. This was commissioned in 1919 and

was named for General George Harrison, the first American governor of

the Philippines. The mineplanter maintained the minefield in the North

Channel of Manila Bay (the Navy maintained the South Channel minefields,

from their base in Cavite), adding to the defenses of the much

better-known "big guns" of Corregidor. (More on the mineplanter and the minefields will come later.) It docked at the North

Dock, where the water taxis dock today.

Although my mother had identified my

father-to-be as a possible romantic interest at the beginning of the trip, something

interfered. A friend had given her a copy of the newly released novel, Gone with the

Wind. My father had to wait until she finished the novel!

Although my mother had identified my

father-to-be as a possible romantic interest at the beginning of the trip, something

interfered. A friend had given her a copy of the newly released novel, Gone with the

Wind. My father had to wait until she finished the novel!

When she was ready, she sent her brother Bruce, a precocious 10 year-old, to go talk with my father-to-be. Then my mother came up to say Bruce had to go do his lessons. One thing soon led to another and they began dating.

Several of my dad’s West Point classmates and their families were also on board, and my mother and father-to-be’s social activity centered on this group. The group was all older than my mother, who had been very protected socially, and she had to learn a lot quickly to keep up with them. Tropical sunsets and an easy life-style made it easy to develop a relationship. She and my father also found a number of dark places on the ship to retreat by themselves for some heavy "necking," but his white summer uniform made him easy to spot.

On arriving in Manila, they went to the Army-Navy Club, the social center for Army and Navy personnel in the Philippines then. Later they boarded the Corregidor-based "Miley," a little passenger boat with a Filipino crew, for the trip to Corregidor, another two hours away.

The relationship continued after they arrived on Corregidor. My mother settled in with her parents and brother in officers’ quarters on the Stockade Level (pictured above), and my father lived at the Batchelor Officers’ Quarters on Topside, a two-story concrete building next to Headquarters,(pictured below).

|

|

|

|

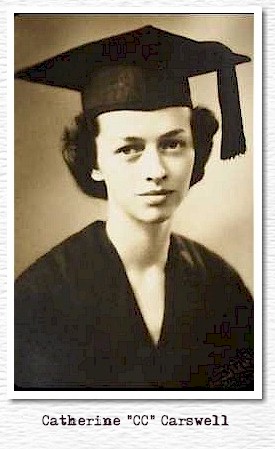

Corregidor’s

busy social schedule led to their being together nearly daily, until my

grandfather decided my mother should finish college. (She had left

Westhampton College in her junior year, when the orders for Corregidor

came). The only place for her to go was the University of the

Philippines in Manila, so she moved to Manila to finish school.

Ex-Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos was a classmate.

Corregidor’s

busy social schedule led to their being together nearly daily, until my

grandfather decided my mother should finish college. (She had left

Westhampton College in her junior year, when the orders for Corregidor

came). The only place for her to go was the University of the

Philippines in Manila, so she moved to Manila to finish school.

Ex-Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos was a classmate.

Fortunately, the mineplanter — with my dad in command — was often in Manila, and their relationship could continue.

Meanwhile, my grandparents also moved to Manila, when he became assistant to Golden W. Bell, the legal advisor to the High Commissioner.

Unlike her sister Annabel, my mother had promised my grandfather she would finish college before marrying. As her graduation approached, their engagement could finally be announced. My Dad gave her an engagement ring, a West Point "miniature" of his big ring. This is a West Point tradition for engagements.

May

3, 1939, she and my father were married in the post chapel, on the

second floor of the Headquarters building on Topside. Three hundred

guests attended, probably most of Corregidor’s officers and their

families. A special boat also brought wedding guests from Manila over to

Corregidor for the 4 PM event. The exit under the traditional arch of

steel, was formed by the crossed sabers of the ushers.

Those who know Corregidor have to wonder how hot and sweaty everyone

must have been at that time of day, at that time of year, while dressed

up for a wedding. A reception followed at the Officers’ Club, the

Corregidor Club.

May

3, 1939, she and my father were married in the post chapel, on the

second floor of the Headquarters building on Topside. Three hundred

guests attended, probably most of Corregidor’s officers and their

families. A special boat also brought wedding guests from Manila over to

Corregidor for the 4 PM event. The exit under the traditional arch of

steel, was formed by the crossed sabers of the ushers.

Those who know Corregidor have to wonder how hot and sweaty everyone

must have been at that time of day, at that time of year, while dressed

up for a wedding. A reception followed at the Officers’ Club, the

Corregidor Club.

My mother had a lovely white net-satin wedding dress made for her in Manila. She got extra attention from the designer, no doubt because of her father’s position in Manila. The designer even came over to Corregidor to dress her for the wedding and to be sure the dress was arranged perfectly through all the events.

As she entered the chapel, rain was falling, and some got on her veil. Many think this is a sign of sadness ahead. My mother didn’t believe in that superstition then, but it did come true only a few years later. Their wedding night was at her parents’ apartment in Manila; her parents stayed on Corregidor that night.

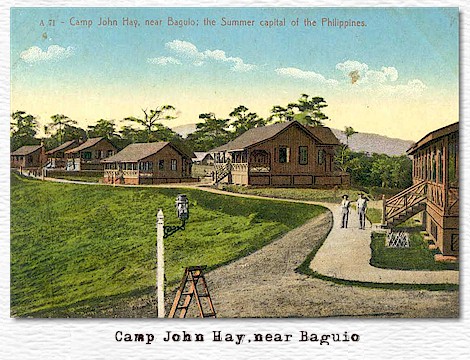

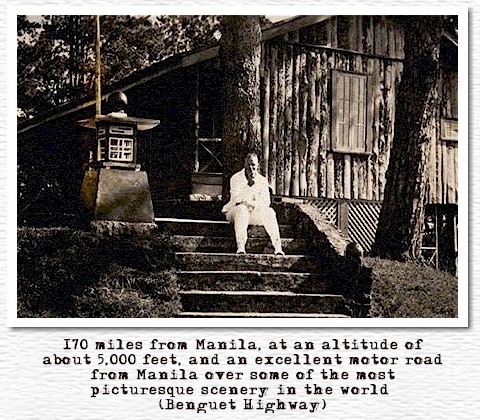

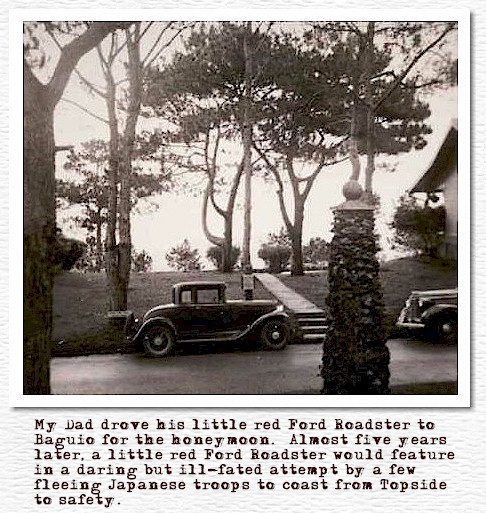

Their honeymoon was at the Army’s Camp John Hay in Baguio, where most Americans in the Philippines and a lot of well-to-do Filipinos went in the summer. Baguio, at 5,000 ft elevation, is much cooler than the rest of the Philippines in the summer. Each American Army officer could stay there one month a year.) They drove there in my dad’s little red roadster, which he had brought from Corregidor on the mineplanter. They stayed in Camp Hay's rustic cabins , ate in the dining hall, walked and explored the local area and its people.

|

|

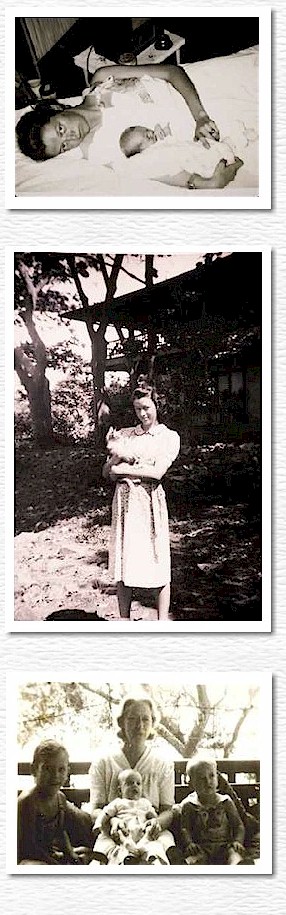

On

their return to Corregidor, they moved into the lower level of the end

unit (closest to the hospital building) in Middleside officers’

quarters, Quarters 102. I arrived on Corregidor 9 months later, in

the delivery room at the Ft. Mills’ Hospital. My father was over in

Manila at the time (he often had to take the mineplanter to Manila), and

the maid had to take my mother to the hospital. I came before my dad

could return to Corregidor.

On

their return to Corregidor, they moved into the lower level of the end

unit (closest to the hospital building) in Middleside officers’

quarters, Quarters 102. I arrived on Corregidor 9 months later, in

the delivery room at the Ft. Mills’ Hospital. My father was over in

Manila at the time (he often had to take the mineplanter to Manila), and

the maid had to take my mother to the hospital. I came before my dad

could return to Corregidor.

Aunt Annabel and Uncle Harry Julian, accompanied now by two children, also arrived on Corregidor again, 10 days after I came. This was their second tour of duty on Corregidor, and they lived just down the row of quarters from my parents. Uncle Harry Julian was now a 1st Lt and commanded D Battery of the 59th . Because my mom and aunt were both married to men named Harry, their conversations included frequent references to "your Harry" and "my Harry."

With a new baby, her sister nearby and her parents in Manila, and supported by servants and with a busy social life as an officer’s wife, things seemed ideal for my mother and her family. Yet, something fearful was entering their idyllic life.

One day in 1941, soon after she arrived on Corregidor the second time, my aunt decided to buy some bamboo furniture, but my grandfather sternly warned her, "Don’t waste your money. You may have to leave suddenly—alone."

It was clear to senior Army officers that war was coming, and coming soon.

![]()

|

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Who said "You can never go home"?

|

FOOTNOTE:

1. Appointment to the USMA at West Point is normally by Congressional appointment. However, 4 places per year (at that time) were allocated to regular Army men who were selected by rankings in the written examination. <Back>