When XIV Corps reached Manila on 3 February, no definite

Allied plan existed for operations in the metropolitan area other than the

division of the northern part of the city into offensive zones. Every

command in the theater, from MacArthur's headquarters on down, hoped--if it

did not actually anticipate--that the city could be cleared quickly and

without much damage. GHQ SWPA had even laid plans for a great victory

parade, à la Champs Elysées, that the theater commander in person was to

lead through the city.1

Intelligence concerning Manila and its environs had been

pretty meager, and it was not until the last week or so of January that GHQ

SWPA and Sixth Army began to receive definite reports that the Japanese

planned to hold the city, although General Krueger had felt as early as the

middle of the month that the capital would be strongly defended.2 The

late January reports, often contradicting previous information that had been

supplied principally by guerrillas, were usually so contradictory within

themselves as to be useless as a basis for tactical planning. Thus, much of

the initial fighting was shadowboxing, with American troops expecting to

come upon the main body of the Japanese around each street corner. Only when

the troops actually closed with the principal strongpoints did they discover

where the main defenses were. When XIV Corps began to learn of the extent

and nature of the defenses, the plans for a big victory parade were quietly

laid aside--the parade never came off. The corps and its divisions thereupon

began developing tactical plans on the spot as the situation dictated.

In an effort to protect the city and its civilians, GHQ

SWPA and Sixth Army at first placed stringent restrictions upon artillery

support fires and even tighter restrictions upon air support operations. The

Allied Air Forces flew only a very few strikes against targets within the

city limits before General MacArthur forbade such attacks, while artillery

support was confined to observed fire upon pinpointed targets such as

Japanese gun emplacements.

These two limitations were the only departures from

orthodox tactics of city fighting. No new doctrines were used or

developed--in the sense of "lessons learned," the troops again illustrated

that established U.S. Army doctrine was sound. Most troops engaged had had

some training in city fighting, and for combat in Manila the main problem

was to adapt the mind accustomed to jungle warfare to the special conditions

of city operations. The adjustment was made rapidly and completely at the

sound of the first shot fired from a building within the city.

The necessity for quickly securing the city's water

supply facilities and electrical power installations had considerable

influence on tactical planning.3 Considering

the sanitation problems posed by the presence of nearly a million civilians

in the metropolitan area, General Krueger had good reason to be especially

concerned about Manila's water supply. Some eighty artesian or deep wells in

the city and its suburbs could provide some water, but, even assuming that

these wells were not contaminated and that pumping equipment would be found

intact, they could meet requirements for only two weeks. Therefore, Krueger

directed General Griswold to seize the principal close-in features of the

city's modern pressure system as rapidly as possible.

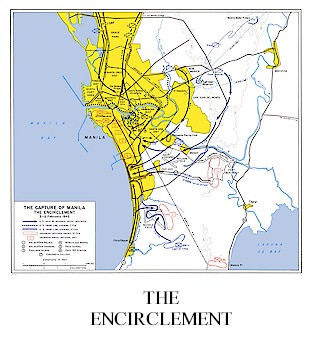

Establishing priorities for the capture of individual

installations, Sixth Army ordered XIV Corps to secure first Novaliches Dam,

at the southern end of a large, man-made lake in rising, open ground about

two and a half miles east of the town of Novaliches. (See Map

"The Approach to Manila") Second came the Balara Water Filters, about five miles northeast of

Manila's easternmost limits and almost seven miles east of Grace Park. (See Map

"The Encirclement")

Third was the San Juan Reservoir, on high ground nearly two miles

northeast of the city limits. Fourth were the pipelines connecting these

installations and leading from them into Manila. Ultimately, Sixth Army

would secure other water supply facilities such as a dam on the Marikina

River northeast of Manila, but not until it could release men for the job

from Manila or other battlegrounds on Luzon.

Third was the San Juan Reservoir, on high ground nearly two miles

northeast of the city limits. Fourth were the pipelines connecting these

installations and leading from them into Manila. Ultimately, Sixth Army

would secure other water supply facilities such as a dam on the Marikina

River northeast of Manila, but not until it could release men for the job

from Manila or other battlegrounds on Luzon.

XIV Corps would secure portions of the electrical power

system at the same time its troops were capturing the water supply

facilities. During the Japanese occupation much of the power for Manila's

lights and transportation had come from hydroelectric plants far to the

south and southeast in Laguna Province, for the Japanese had been unable to

import sufficient coal to keep running a steam generator plant located

within the city limits. It appeared that Laguna Province might be under

Japanese control for some time to come, and it could be assumed that the

hydroelectric plants and the transmission lines would be damaged. Therefore,

Sixth Army directed XIV Corps to secure the steam power plant, which was

situated near the center of the city on Provisor Island in the Pasig.

XIV Corps was also to take two transmission substations

as soon as possible. One was located in Makati suburb, on the south bank of

the Pasig about a mile southeast of the city limits; the other was presumed

to be on the north bank of the river in the extreme eastern section of the

city. It is interesting commentary on the state of mapping, considering the

number of years that the United States had been in the Philippines, that the

second substation turned out to be a bill collecting office of the Manila

Electric Company.