|

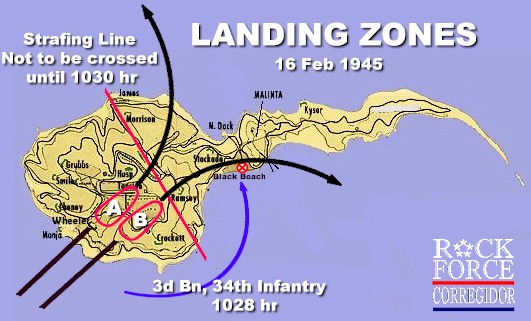

The flight pattern for A Field passed over Point 7 which is Battery Wheeler. 'A' Field planes, veered north of this line whilst 'B' Field planes veered east. It was the E Company, together with the majority of 2d Bn HHC, leaving from San Jose (Elmore Strip) that turned north into the anti-clockwise corridor. A good number of 'E' Company men landed well short of their landing zone, "A" Field. Among these was Pfc. Fitzhugh Millican, who was a member of the mortar platoon, whose stick was led by S/Sgt. Edward Gulsvick.

|

![]()

|

|

Ahead of him in the stick, and killed in the ravine were S/Sgt. Edward Gulsvick, Pfc Jimmie T. Rovolis, Pfc Matthew D. Musolino and Pfc Emory M. High. All four of these men died at the hands of the Japanese.

|

|

The incident with S/Sgt. Gulsvich vindicates the practice of having a Thompson man lead each stick. For paying the supreme price, S/Sgt Gulsvich was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation's second highest award. Jimmie Rovolis and Emery High's were taken by the Japanese and their bodies were never found. They remain MIA. Musolino's body was only found after the 503d had returned to Mindoro.

Musolino's dog tags were found at Battery Wheeler on February 16, 2008 - a full 63 years after the jump. (See story.)

1st Lt. Hudson Hill, E Company commander, landed in one of the three buildings of the NCO Quarters. He struck the building as he was descending and fractured several teeth. He collected the E Company men in the area and was attempting to begin rescue operations when 1st Lt. Edward T. Flash, 2nd platoon leader, F Company, made his appearance with his platoon to occupy the NCO Quarters as part of the battalion defensive perimeter.

|

|

Soon after Ed and his platoon arrived, Col. Jones and Major Caskey arrived and instructed Lt. Hill to take his men and join the rest of the company who had assembled under Lt. Abbott at the Topside barracks. Col. Jones ordered Ed to make the rescue of men trapped in Cheney Ravine his immediate mission in addition to forming a defensive perimeter at the NCO Quarters. They rescued the last living man, S/Sgt Leonard R. Ledoux, who was heard crying out for help, in the ravine the next morning. Ed, Pfc's Anthony Lopez, Robert O'Connell, and Angelos Kambakumis were all wounded in a daring rush into the ravine to rescue Ledoux. Despite their efforts S/Sgt Ledoux died of his wounds. Thus the fifth E Company man died as a result of enemy action during the jump. When the company left Mindoro, 1st Lt. Hill was commanding, 1st Lt. Abbott was executive officer, 1st Lt. Whitson was 1st platoon leader, 1st Lt. Roscoe Corder was 2nd platoon leader, 1st Lt. Atchison was 3rd platoon leader, 2nd Lt. Ball was mortar platoon leader, and 2nd Lt Crawford was assistant platoon leader in the 1st platoon. After Dick Atchison was wounded, Lewis Crawford was assigned to command his platoon. Thus on the first day E company had lost five men killed in action and 21 from wounds or injuries during the jump. That was almost twenty percent, the heaviest of any of the 2d Battalion Companies.

"B" Field was far less deceptive. According to USAFFE Report #308 written by Lt. Colonel Robert Alexander and Major Wayne O. Osmundson, the usable area of "B" Field was about 75 yards longer than and the same width as compared to "A" Field. Landings short of "B" Field would put the jumper in deep, heavily wooded Crockett Ravine, unarguably Japanese territory, whereas landings short of "A" Field, such as Don Abbott's, placed one at the risk of serious injury in the debris field.

|