|

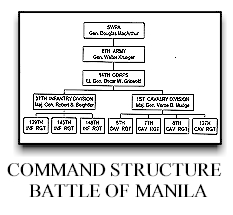

The principal U.S. units

involved in the Battle of Manila, the 37th Infantry Division and

the 1st Cavalry Division, had not fought in cities before, but

they apparently had to some extent been trained for city fighting and

followed established doctrine for urban warfare

(see

Figure 1).

Their methods differed from doctrine on only two points: air strikes were

not allowed within the city, and artillery fires in the early phases of the

battle were prohibited except against observed pinpoint targets known to be

enemy positions. Both the 37th Infantry Division and the 1st

Cavalry Division had had abundant recent experience in jungle warfare and

were trained, organized, and equipped for fighting in restrictive terrain.

While jungle fighting and urban fighting differ in many respects, tactically

both fights have an important similarity in that both take place in

restrictive terrain. Although by happenstance more than planning,

these units were fairly well prepared for the kind of tactical fighting they

would face in Manila.

[xii] (see

Figure 1).

Their methods differed from doctrine on only two points: air strikes were

not allowed within the city, and artillery fires in the early phases of the

battle were prohibited except against observed pinpoint targets known to be

enemy positions. Both the 37th Infantry Division and the 1st

Cavalry Division had had abundant recent experience in jungle warfare and

were trained, organized, and equipped for fighting in restrictive terrain.

While jungle fighting and urban fighting differ in many respects, tactically

both fights have an important similarity in that both take place in

restrictive terrain. Although by happenstance more than planning,

these units were fairly well prepared for the kind of tactical fighting they

would face in Manila.

[xii]

MacArthur set the Manila

operation in motion personally on the night of 31 January by visiting 1st

Cavalry Division headquarters, then still in the vicinity of the Lingayen

beachhead. The division set out for Manila at one minute after

midnight on 1 February, without 24-hour reconnaissance or flank protection.

It employed “flying columns,” battalion-sized forces entirely on wheels to

expedite the advance, covered the 100 miles to Manila in 66 hours, and

entered the outskirts of the city on 3 February. MacArthur visited the

other major unit that would assault Manila, the 37th Infantry

Division, on 1 February and set it in motion toward the city. It

reached the Manila area on 4 February.

[xiii]

MacArthur ordered the 1st

Cavalry to seize three objectives: Santo Tomás University, where U.S. and

Allied internees were held by the Japanese; Malacanan Palace, the

presidential residence; and the Legislative Building. The division’s

flying columns moved easily to capture the first two of these, but heavy

Japanese resistance kept it from reaching the Legislative Building which lay

south of the Pasig River.

[xiv]

On 3 February, the 8th

Cavalry Regiment entered and liberated Santo Tomás at 2330. The

guards, mostly Formosans, offered little resistance. Some 3,500

jubilant internees were freed, but 275 Americans were still held hostage in

the education building by 63 Japanese troops. On 5 February, these 63

were escorted through American lines in exchange for release of the

hostages. Suddenly, the 1st Cavalry Division was

responsible for feeding and otherwise accommodating the 3,500 freed

internees. This task was complicated by the fact that Japanese forces

had cut the division’s lines of communication, by blowing up the Novaliches

bridge. By 5 February, the 1st Cavalry was very low on food

for both itself and the internees. The division was surrounded, as

historians of the plodding 37th Infantry Division point out.

The 37th Infantry Division had to “rescue” the 1st

Cavalry Division on 5 February by breaking through Japanese positions and

reestablishing 1st Cavalry’s supply. A convoy with food and

ammunition reached the division on the evening of 5 February. The

division’s lines of communication continued to be insecure, however.

Japanese forces killed twelve 1st Cavalry drivers during these

weeks. [xv]

Administering a city requires

not only looking out for the needs of the individual inhabitants, but also

safeguarding city functions such as water and power. Lt. Gen. Krueger

was therefore eager to preserve the water and power supplies of Manila as

U.S. forces entered the city. Manila’s steam power generating plant

was on Provisor Island, on the south side of the Pasig, and elements of the

37th Infantry Division would not reach it until 9 February. Manila’s

water system lay northeast of the city, and securing and protecting it was

one of the first missions assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division.

The main features of the system were the Novaliches Dam, the Balara Water

Filters, the San Juan Reservoir, and the pipelines that carried water among

these and to Manila. From 5 to 8 February, the 7th Cavalry

Regiment captured all of these facilities intact, despite some being wired

for demolitions. They spent the rest of the battle for the city

guarding these installations. [xvi]

The 37th Infantry

Division moved into Manila shortly after the 1st Cavalry

Division, on an axis of advance just west of 1st Cavalry

Division’s. On 4 February, the 37th Infantry Division moved

through the working class Tondo residential district adjacent to the bay

and, on its left flank, reached the Old Bilibid Prison where it discovered

1,330 U.S. and Allied prisoners of war and civilian internees left under

their own recognizance by retreating Japanese. The division left them

there for the time being because the area outside was not yet secure.

On 5 February, however, fires in the city threatened Bilibid, so the 37th

Infantry Division had to evacuate hastily the 1,330 internees and care for

them elsewhere. All available troops and transportation assets were

devoted to this emergency move, which was complicated by the fact that many

internees were unable to walk. Divisional troops were heavily engaged

in this work, and the internees were moved to the Ang-Tibay Shoe Factory

north of the city -- the 37th Infantry Division’s command post.

The division provided cots and food for the internees and dug latrines.

The next day, the fires subsided and the internees were moved back to

Bilibid, where their needs could finally be provided for more thoroughly. [xvii]

In the vicinity of Bilibid Prison and

southward toward the Pasig, the 37th Infantry Division and the 1st

Cavalry Division began encountering major Japanese resistance (see

Map 1). As

the 1st Cavalry Division moved southward on multilaned Quezon

Boulevard, it encountered a defended barricade just south of Bilibid Prison.

The Japanese had driven steel rails into the roadbed, wired a line of trucks

together, laid mines in front, and covered the whole roadblock with fire

from four machine gun positions. The barricade of trucks was unusual

in Manila, but the minefield covered by obstacles and machine guns would be

a common feature of the Japanese defenses both north of the Pasig and

elsewhere.

[xviii]

The 148th Infantry

Regiment had to cross the Estero de la Reina bridge to approach the Pasig

but was stymied by mines and five 500-pound bombs on the bridge, by blazing

fires in buildings to its right and front, by exploding demolitions and

gasoline drums, and by machine gun fires trained on intersections and

streets. Most of the American units approaching the Pasig probably

faced similar challenges. Another feature of the early fighting north

of the Pasig was that the Japanese Noguchi Detachment on 5 February set fire

to major buildings near the river in order to halt the U.S. advance; the

Japanese also exploded demolitions in major buildings and in military

facilities. Until these fires could be brought under control on 6

February, U.S. personnel were forced back from the river, and the U.S.

advance was delayed. The 37th Infantry Division also on 5

February faced interactions with civilians that it would see more of.

“. . . swarms of the native population . . . crowded the streets cheering

the American troops, forcing gifts upon them, and . . . engaged in

unrestrained looting.” Both the jubilation and the looting obstructed

military operations, and the 37th Infantry Division would see

more of both. [xix]

By 7 February, U.S. forces were

in control of Manila north of the Pasig. Surviving Noguchi Detachment

troops had withdrawn south across the river and destroyed all of the

bridges. On 5 February, Lieutenant General Oscar W. Griswold,

commander of 14th Corps, extended the 37th Infantry

Division’s area of control eastward into what had been the 1st

Cavalry Division’s zone, and also gave 1st Cav responsibility

farther to the east. This change made possible the next phase of

operations in which the 37th Infantry Division would fight its

way across the Pasig in the downtown area while the 1st Cavalry

Division swept wide around the city, east, south and west again to the bay,

thus isolating the Japanese defenders from any source of resupply or relief. [xx]

Many cities contain harbors or lie on

rivers so that urban warfare frequently requires some amphibious warfare

assets. On 7 February, the 37th Infantry Division began the

difficult work of crossing the Pasig. The 148th Infantry

Regiment crossed first at 1515. Troops had the benefit of an

amphibious tractor battalion and thirty engineer assault boats. They

were covered by artillery fire and smoke and departed from four different

concealed launch points. The first wave crossed without incident, but

the second was raked by machine gun and automatic cannon fire from Japanese

positions lying to the west on the south bank of the Pasig. These

fires shattered some of the plywood boats and oars. Troops paddled on

as best they could with oar handles and rifle butts. The landing area

was the Malacanan Gardens, the only point on the south bank without a

seawall that would obstruct amphibious tractors and disembarkment.

Troops found few Japanese in the disembarkment area and established a

bridgehead with little difficulty. On 8 February, the 37th

Infantry Division built a pontoon bridge across the Pasig to support the

bridgehead. The bridge had two tracks, one for personnel and one for

vehicles. No sooner was the bridge built, however, than hundreds of

Philippine civilians began pouring across it from south to north, trying to

escape the fighting.

[xxi]

|