|

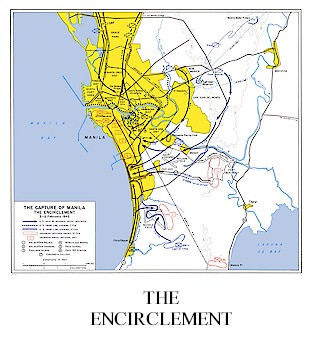

The 37th Infantry

Division completed its crossing of the Pasig on 8 February, and began

deploying south and west out of its bridgehead.

[xxii] The hardest fighting the 37th Infantry Division

would face in Manila was in this district south of the river, between the

crossing of the Pasig on 7 February and the assault on Intramuros on 23

February. Japanese defenders had established a series of strongpoints

in major buildings in this area and contested them fiercely. On 8

February, the 129th Infantry Regiment moved westward along the

Pasig shore and on 9 February crossed the Estero de Tonque by boat to

assault Provisor Island where Manila’s steam electrical generation plant was

located. The Japanese defenders placed sandbagged machine gun

emplacements in buildings and at entrances and were able to blanket the

whole island with machine gun positions to west, southwest, and south.

The 129th Infantry Regiment approached the island in engineer

assault boats, then conducted a cat and mouse struggle with Japanese for

control of the buildings, fighting with machine guns and rifles among the

structures and heavy machinery. The 129th was able to

secure the island on 10 February, but lost twenty-five troops killed in the

process. The vital electrical generation equipment, which Krueger in 6th

Army’s plans had hoped to capture intact, was hopelessly damaged by both

Japanese defenders and American fires. [xxiii]

While the 129th

Infantry Regiment swept west out of the Malacanan bridgehead, in a close

arc, the 148th Infantry Regiment swept in a broad arc, southeast,

then back westward. The two regiments moved in line through the

Pandacan district to the southeast with relatively little resistance, but

then found themselves in a pitched battle in the Paco district for control

of the Paco Railroad Station, Paco School, and Concordia College. On 9

February, both 129th Infantry Regiment and 148th

Infantry Regiment advanced only 300 yards. [xxiv]

Given the new intensity of the

fighting in the 37th Infantry Division’s sector, the division

requested and received a lifting of the restrictions previously

imposed on artillery fires. To that point, fires had been restricted

to observed enemy positions, but had failed to force an enemy withdrawal.

Thereafter, fires would be allowed “in front of . . . advancing lines

without regard to pinpointed targets.” In other words, fires could

blanket enemy positions U.S. troops were assaulting. “Literal

destruction of a building in advance of the area of friendly troops became

essential,” as the 37th Infantry Division Report After

Action put it.

[xxv]

The Japanese defensive positions

U.S. troops encountered in the Paco district were well developed, as they

would be for the rest of the battle. Japanese observers were present

in almost every building. At street intersections, machine gun

pillboxes were dug into buildings and sandbagged so as to cover the

intersection and its approaches. Artillery and anti-aircraft weapons

were placed in doorways or in upper story windows. Most streets and

borders of streets were mined, using artillery shells and depth charges

buried with their fuses protruding an inch or so above the surface.

The streets were a fireswept zone forcing Americans to move between streets

and within buildings. Americans entered and searched each building and

house, top to bottom, and neutralized whatever enemy they found. [xxvi]

Besides controlling the urban

terrain with fires, the Japanese in the Paco district and points west had

fortified particular sturdy public buildings as urban strongpoints. In

some cases, these buildings were mutually supporting. The first of the

urban strongpoints the 37th Infantry Division encountered was the

Paco Railroad Station. The Japanese had machine gun posts all around

the station, and foxholes with riflemen surrounded each machine gun post.

Inside at each corner were sandbag forts with 20mm guns. One large

concrete pillbox in the building housed a 37mm gun. About 300 Japanese

troops held Paco station. The Japanese placed observers in the Paco

church steeple, and the station could not be approached until the Paco

School and other neighboring positions had been cleared. [xxvii]

Americans inched forward to

within 50 yards of the Paco station building, set up a bazooka or BAR, and

pounded the building as riflemen rushed forward covered by fire. The

station was finally seized at 0845 on 10 February after 10 assaults.

Between the Provisor fighting and the Paco station fighting on 9 and 10

February, the 37th Infantry Division suffered 45 killed in action

[KIA] and 307 wounded in action [WIA]. [xxviii]

American

troops would have much more such fighting ahead. Once the 129th

Infantry Regiment and the 148th Infantry Regiment had secured

Provisor Island and the Paco Railroad Station respectively, both swept

westward toward Intramuros and the bay. The 129th Infantry

Regiment collided with the Japanese strongpoint at the New Police Station,

and the 148th Infantry Regiment collided with the strongpoint of

the Philippine General Hospital (see

Map

- The Drive Toward Manila). The 129th

Infantry Regiment began its assaults on the New Police Station on 12

February. The strongpoint consisted of the police station itself, the

shoe factory, the Manila Club, Santa Teresita College and San Pablo Church.

By nightfall, the 129th Infantry regiment had consolidated its

lines on Marques de Camillas Street fronting the strongpoint.

Maintaining lines--keeping units that advanced faster than others from

leaving hazardous gaps in the line--offered many challenges in the highly

compartmented urban environment. American

troops would have much more such fighting ahead. Once the 129th

Infantry Regiment and the 148th Infantry Regiment had secured

Provisor Island and the Paco Railroad Station respectively, both swept

westward toward Intramuros and the bay. The 129th Infantry

Regiment collided with the Japanese strongpoint at the New Police Station,

and the 148th Infantry Regiment collided with the strongpoint of

the Philippine General Hospital (see

Map

- The Drive Toward Manila). The 129th

Infantry Regiment began its assaults on the New Police Station on 12

February. The strongpoint consisted of the police station itself, the

shoe factory, the Manila Club, Santa Teresita College and San Pablo Church.

By nightfall, the 129th Infantry regiment had consolidated its

lines on Marques de Camillas Street fronting the strongpoint.

Maintaining lines--keeping units that advanced faster than others from

leaving hazardous gaps in the line--offered many challenges in the highly

compartmented urban environment.

The bitter fighting at the New Police

Station went on for eight days, until 20 February. On 17 February, the

relatively fresh 145th Infantry Regiment replaced the battle-worn

129th Infantry Regiment. The first tanks arrived on 14

February to assist the Americans. Tanks were not present earlier in

this part of the city because they could not cross the Pasig. Once

committed, they were used for direct-fire bombardment on the New Police

Station and in later operations.

The American method was to

bombard the resisting structure with tanks and 105-mm guns and howitzers,

then to conduct an assault. Sometimes the Japanese defenders

counterattacked, driving the Americans out, in which case the whole process

was repeated. The Japanese had trenches and foxholes outside the

buildings and numerous sandbagged machine gun positions inside. U.S.

artillery reduced the exterior walls to rubble, but infantry still had to go

into the buildings and clear them room by room and floor by floor. The

preferred American method was to fight from the roof down, but the troops

were unable to do this at the New Police Station, probably because no

structures were near enough to give roof access. Thus, they had to

work from the ground up. Japanese defenders cut holes in the floors

and dropped grenades through them. They also destroyed the stairways

to prevent access to upper stories. Nevertheless, the145th

Infantry Regiment managed to secure the New Police Station strongpoint by 20

February. [xxix] |