|

-5-

From this position the Main Post Hospital stood out very prominently below me to

the north. It was to be one of Company "E"'s first objectives once it arrived

and had assembled. A little closer to the Barracks was the old Commissary

building. This stood on a bench which would be a good place for the Company to

set up its perimeter defense the first night on the Island. The elevated terrain

would provide a commanding view of the area in front of it.

Looking to the northeast, far enough away they were too small to identify, some

men were running across an open area on Morrison Hill.

All of a sudden there was the sound of rifles and a light machine gun opening

up. The men I had seen began to stumble and fall, laying still. At first I was

shocked we would be losing men so fast to enemy fire. Suddenly, it became

evident the men I was seeing were not ours but were Japanese troops running away

from third battalion men who were firing on them. There must have been ten or

twelve Japanese who had died for their emperor right before my eyes.

Near a part of the Barracks, which had been demolished by an explosion, I found

a location where we would set up our Command Post when the people in Company

Headquarters arrived. This was well to the west of the center of the building.

It would place us close, but not too close, to the Battalion and Regimental

Command Posts, which were both located in Mile Long Barracks.-

As the time approached 10:30 the sound of shelling could be heard in the

direction of Black Beach at Bottomside. There were too many buildings in the way

to be able to observe the landing but from the amount of small arms fire, in

addition to the shelling, it was evident the 3rd Battalion of the 34th Infantry

were landing according to the schedule.

The overall plan for the Rock Force was for the 34th Infantry to immediately

attack up the slope of Malinta

Hill,

secure the top and to move on beyond to cut the island so that Japanese

reinforcements from the east end of the island could not reach the west end.

This could be a difficult assignment for these men because Malinta Hill was a

steep, treacherous looking place. From the end of the Mile Long Barracks the

entrance to Malinta Tunnel could just be made out. There was a lot of fire being

poured into it. Shells were exploding nearly constantly.

Having no official duty which needed attention, I had a little time to look at

the buildings and the layout of Topside and reflect on how they must have looked

in the days when Fort Mills was one of the regular duty posts of the Army. The

buildings were badly pocked from bullets. Some of the buildings had been hit by

shells or bombs and had big parts missing or collapsed. Practically all roofs

had been blown off by concussion. Regardless, the place had a majesty about it

which held a person in awe. The Mile Long Barracks, in particular, was a wonder.

One felt it must have, certainly, been the largest single barracks building

anywhere. The whole building was three stories high. Although little remained

it was evident the first floor held the various headquarters for the 59th Coast

Artillery Batteries, along with the kitchens and mess halls, the showers,

storerooms, etc. The second and third floors, reached by concrete staircases,

had large squad rooms. It appeared the Non Commissioned Officers must have been

quartered elsewhere because there were no smaller rooms, such as the temporary

wooden barracks had at the end of each squad room.

Across the road from the Mile Long Barracks were the remains of a tram stop and

the ties of the rail system. The rails apparently had been taken up by the

Japanese invaders. There was a large building near the tram station which was

the movie theatre. It had a very substantial looking ticket window, much

different than the flimsy glass and light metal affairs of the theatres back in

the states. Somehow the rumor made the rounds the last movie to play at the

Topside theater was Gone With The Wind. I doubted this since I remembered having

seen the movie in 1940, well before the last film would have been shown on

Corregidor.

The last C-47 which had dropped the first wave had not left the area until 0940

for its return flight to Mindoro to pick up the second wave. Mindoro was 150

miles south, or a bit over an hour's flying time, point to point. Of course

there would, likely, be time in the pattern over the two airfields used by the

317th. To make the scheduled 1250 second drop would take some doing. Each plane

would have to be refueled, time could be spent rigging the artillery packs

Where they needed to be mounted.

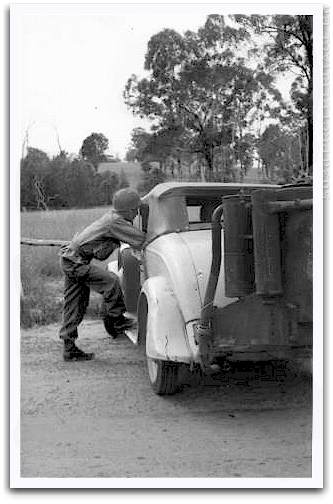

There would be no need to worry about the Second Battalion being ready and

anxious to board when given the go-ahead by the Air Corps crews. They were at

Hill and Elmore strips waiting when the planes returned from dropping the first

wave. The heavily loaded men would take a bit of shoving and hauling, however ,

because they carried so much weight it was about

all they could do to waddle to the ladder leading to the door. Then

it was a case of men behind them on the ground giving a shove at the same the

men in the plane offered a hand and pulled them aboard. Each man, in his

eagerness to get under way, had forgotten how hot it would be in the plane as it

sat in the scorching hot tropical sun. The minute the men got in the plane the

sweat would pour from them and not just because of their nervousness. As soon as

the plane would get in the air and up to the eight or ten thousand feet altitude

they would fly at it would be so cold each man would be near freezing. There

seemed to be no happy medium.

The planes, after take-off formed into an echelon formation to make fighter

coverage more effective. The flights continued in that order until a few miles

south of Corregidor when they again formed into two, evenly spaced columns and

steered toward the two landing zones. The lift began to drop its troopers at

1250 and completed their mission at 1342.

During the time the first wave of jumpers had been on the ground, the wind had

picked up. As the time for the second jump approached the velocity had passed 25

knots in gusts. Since it looked as if it were going to get stronger as the day

went on, the people on the ground wished for the second wave to get there as

soon as possible.

Jumpmasters of the second wave had been instructed to count 10 seconds past

their Initial Points because of the increased wind velocity. Even with this

correction, a number of men were blown over the cliff, landing on the steep

slopes below the rim. Staff Sergeant Harry D. Clearwater was one who landed well

down the slope, breaking both legs. Staff Sergeant Robert V. Holt, Jr. landed

somewhat below Clearwater and somehow lost his weapon. Climbing toward the rim,

Holt found Clearwater and borrowed his Thompson Sub Machine Gun, promising to

send help. The help came, but not until 36 hours later.

The wind seemed to have shifted to a little more from the east than for the

first wave. Some of the aircraft did not compensate fully for this change and

flew a course too far to the west over the jump fields. As a consequence a

number of men were blown off the western edge of Landing Zone “A”, landing

around three large, two story buildings which housed senior Non Commissioned

Officers’ families prior to the war. Others landed near a large building which

been a radio station. Even from my vantage point two or three hundred yards

away, I could tell these buildings were effective anti-airborne hazards with

ragged concrete and exposed reinforcing-rods ready to impale or mangle a man.

Standing on the edge of Landing Zone “A”, next to the Mile Long Barracks and

watching what was happenig I knew what should have been done but, of course, was

powerless to do anything because I did not have contact with people in the

planes. If someone could have told them to fly about three hundred feet to the

east, these misses would not have happened. It is a very helpless feeling to

watch disasters happen and not be able to do anything to help.

While I watched, one man with almost a complete a streamer (his chute pulled

from his pack but not opened) crashed into the Mile Long Barracks with an impact

no man would be able to survive. But there were medical people in that area to

do what they could for him.

The first men hitting the silk seemed to be the sign for Japanese troops to

commence firing, particularly down in the Battery Wheeler area and in the upper

Cheney Ravine -area. Rifle and Machine Gun fire had been heavy east of Landing

Zone “B” ever since the first wave had landed and, particularly, since the 34th

Infantry had landed at Black Beach. Now that fire seemed closer and heavier than

ever.

I would be watching a man over the drop zone, with his chute full and doing its

job, swinging his arms and legs around trying to control his descent so as to

land where he wanted to. More than once I would see the man, suddenly, slump in

his harness as he had been hit by fire from the ground.

Several of the airplanes were struck by the light anti-aircraft fire from the

Japanese. I heard about that a bit later. It was not immediately evident while

watching from the ground.

When we landed with the first wave the Japanese were, mostly, in their shelters

to avoid our Air Corps bombing and strafing and were not out in the open ready

to shoot at us in the air. I was very lucky to be in the first wave. Because men

from the first wave were spread out over a large area of Topside, the Air Corps

fighters and bombers couldn't cover the second wave. By that time the Japanese

were ready for them and the jumpers were met with constant rifle and machine gun

fire.

Shortly, men from Company "E" began to work their way to where I was waiting for

them. First Lieutenants Joe M. Whitson, Jr., Roscoe Corder and Second

Lieutenants Lewis B. Crawford and Emery N. Ball arrived. I told them to head

down to the Western end of the Mile Long Barracks which was the Company’s

assembly point and try to keep the men spread out as they came in.

Having been on the island for around five hours I felt like a Corregidor veteran

as the Company began to arrive. Although it had been an exciting period, the

nervousness of the first few minutes, not knowing what to expect, had worn off

and I was as cool and collected as could be expected under the circumstances.

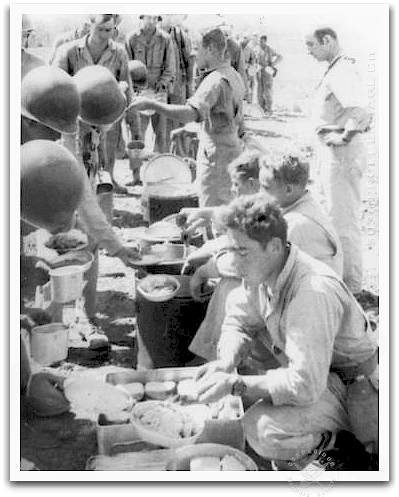

The 503rd had been in the tropics for a long time and the men had become as well

acclimated to the heat and humidity as anyone from temperate climates could

expect to be. Everyone had worked up a good sweat and pulled out their canteens

for a swig of water to freshen their mouths. On other operations we had gone in

with only one issue canteen. This time the planners had smartened up. Every man

was issued a second canteen and landed with each of them full. For some unknown

reason I had always been able to survive with less water than most. I had begun

using water out of my right hand canteen. Now I shook it and found it was at

least three quarters full. Some of the men coming in from the Landing Zone had

started on their second. I reminded them they had better slow up because we

didn't know when we would get any more. We had been warned that we could not

expect to find water on the island and that it could be as much as several days

before we could receive our first resupply. First priority for resupply during

the first day or so would be given to ammunition and weapons to replace those

which might have been lost or damaged.

I kept expecting First Lieutenant Hudson C. Hill, the Company Commander, but he

did not come in. I kept trying to raise him on the Walkie-talkie SCR 536 Company

network but to no avail. The SCR 536 had been notoriously fickle since they had

first been issued. They were of absolutely no use unless there was a perfect

line-of-sight between the two instruments. Apparently Hill was in a building or

behind a knoll where we could not see each other.

Finally, we made contact. Apparently Hill had moved so he was within range and

had a line-of-sight. He was asking me to get some artillery fire down in the

area of the NCO Quarters to take the pressure off him so he could get up to the

CP. Upon his insistence I went looking for an artillery officer but couldn't

find any. As near as I could tell the only completely assembled artillery piece,

at that time, was the one I had seen on the other side of the Mile Long

Barracks. There had been no officer with them. After quite a lot of scurrying

around looking for someone with authority in the Artillery, with no success, I

gave up. Shortly afterward Hill made his way to the CP very upset that he had

not received the artillery fire he wanted.

|