|

-7-

Major Woods called a meeting of his Company Commanders at 2000 and laid out the

plan of attack for the following day. Following the meeting the Company

Commanders, with the exception of Captain John Rucker returned to their units to

prepare for the next day.

At about 2130 a mortar shell

landed in

the Command Post crater killing Major Woods, instantly.

Several others from “B” Company were killed and most

of the remaining staff were wounded. The Battalion was left without its

Commanding Officer, its S-1, S-2 and S-3. Major John N. Davis, the Battalion

Executive Officer, assumed command.

During the night "B" Company on the North side of the Island was hit by a Banzai

attack

by a

large force which was repulsed with 135 enemy killed. Later a prisoner of war

reported that originally a force of 600 had been planning attack but had been

caught by an artillery barrage just as they were preparing to move and that

about 300 had been killed. Our artillery reported the fire had been a searching,

harassing exercise which turned out to be highly effective.

Because of the disruption caused by the loss of Major Woods, the Battalion

attack did not begin until 1045 on the morning of 25 February. Heavy resistance

was experienced almost immediately as the forces approached Water Tank Hill.

By the evening of 25 February the companies had secured the high ground to the

north of Monkey Point and the western end of Kindley Field. The Third Battalion,

closely following the First Battalion, continued to mop up installations

bypassed earlier.

Early in the morning of 26 February the attack continued toward the east with

"A" Company on the right, or south side of the road to Kindley Field and "B"

Company on the left. "C" Company followed "A" Company in reserve. Captain

William Bossert remembers being nervous because he

was unable to have any troops down along the waterline on the south side but,

since there was a cliff on that side, he did not see how he could put anybody

down there and yet have them under his control.

"A" Company came under fire from a machine gun on the southern slopes of the

high ground above Monkey Point. One of the tanks was brought up to assist. It,

too, came under fire from an entrance to what the 503rd men knew as a radio

tunnel. It was not difficult to believe the tunnel had something to do with

radios because there was a whole forest of tall antenna poles located throughout

the whole area. The antenna wires were, mostly, missing but the original layout

was very evident.

The tank took up a position on a small mound in front of the tunnel and began

firing into the entrance with its cannon.

Suddenly, there was a catastrophic explosion, greater than any of the many which

had taken place since the 503rd had landed on 16 February. The whole hill seemed

to be lifted hundreds of feet into the air. Large boulders could be seen flying

through the air. Chunks of concrete were everywhere. The sun was blotted out by

the cloud of dirt which was in the air. Men who were on top of the mound were

flung far into the air. Then all of the many cubic yards debris which had been

flung up began to come down. Later reports were that Naval vessels laying a mile

away were hit by falling boulders.

The tank was lifted into the air and blown on its back about 50 feet from where

it had been located. Only one of the crew survived and was rescued after being

trapped for a number of hours. In order to get him out a cutting torch had to be

obtained from the Navy.

PFC Carl Bratle was near the site of the explosion. The explosion itself had

caused him to bleed from his mouth and ears. But when he looked up and saw all

the debris ready to fall on him, he dropped his M-1 rifle and leaped over to

embrace one of the big radio antenna poles. Fortunately, this worked as a

shelter even if he was hit by rocks and dirt. When the worst of the debris had

fallen he looked down at his rifle. A rock two feet in diameter had hit the

stock and completely smashed it. Not to worry, there were plenty of rifles

laying around men who had not been as lucky as Carl.

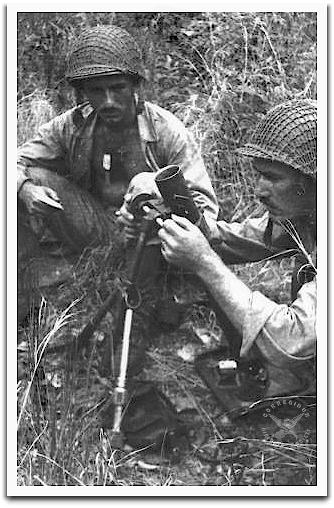

Along the same lines, 2nd Lt. Fred A. Goetz, Mortar Platoon Leader in "B"

Company who was, perhaps two or three hundred yards from the explosion with his

mortarmen, looked up and saw the cloud of corruption. He quickly called for his

men to stand up. He reasoned a standing man would make a smaller target for the

heavy stuff which was coming down. It worked because he had no serious

casualties in his platoon.

Captain Bill Bossert was on the walkie-talkie radio, talking with First

Lieutenant William J. Sullens, platoon leader of the platoon Bossert had

detailed to support the tank which was firing into the tunnel. The radio went

dead as the tank landed on top of Sullens and he was killed instantly. Bossert

was smashed into the ground by the falling debris and nearly buried alive. As it

was, a rock landing on his back crushed his chest as several ribs were broken.

His men dug him out of the dirt and Bill could breathe again--barely.

The 503rd had known nothing about the radio tunnel. It was not until afterward

it was learned this tunnel had been used by Navy personnel as an intelligence

gathering facility.

On the day prior to the big explosion I had been sent over to the east side of

Malinta Hill to look over the situation as it stood at that time. It was not

clear whether companies from the Second Battalion might be called upon to assist

in the move toward the east. That was on 25 January before the big explosion.

After climbing to the ridge to the east of Malinta Hill I was able to get a very

good idea of the orientation of the units and where the major resistance was

coming from. Some of the people I talked with suggested I take a side trip down

to Officer's Beach to see the "Q" Boats which had been turned up. I dropped down

to the beach and, after looking the boats over, continued toward the west past

Bottomside and on up to the Company location.

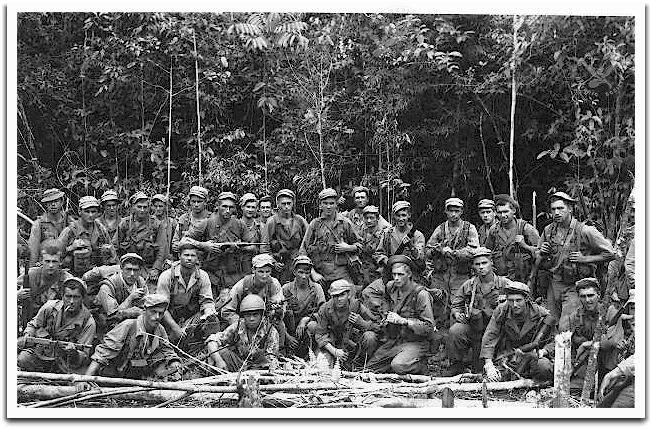

The First and Third Battalions continued with the clearing of the east end of

Corregidor while the Second Battalion continued its search and destroy mission,

digging Japanese out of their hiding places. It always seemed "Higher

Headquarters" knew more about the local operation than we did. They had declared

the Island to be under control early in the mission. While, from a strategic

standpoint, they were undoubtedly right--shipping could and did begin to use the

South Channel to enter Manila Bay and harbor, the troops remaining on the

island, however, would have questioned how strong that control was.

A couple of days prior to his coming, word was received General Douglas

MacArthur was going to visit on 2 March, very near three years since he had been

taken off by PT Boat on 12 March 1942. Preparations began to be made for a

ceremony to greet him as he stepped of a much newer PT Boat.

Each Company was given a part to play in the ceremony. There would be a

representa tion from each company to attend the formal rededication to take

place at the old flag pole across the road from the old Headquarters of Fort

Mills. "E" Company was also required to furnish a detail to guard the route

from Bottomside to Topside. On 1 March I, and representatives of other companies

were taken along the route to have our area of responsibility pointed out to us.

Later, I took our detail down to a stretch of the road near the Middleside

Barracks. The men were spaced at an interval of about ten yards and instructed

to remain at ease but alert for any evidence of Japanese attempts to get to the

General. I am certain the men did their duty as they were directed but would be

very surprised if they did not sneak a look at MacArthur and the group with him

as they went by.

For about a week prior to 1 March I had been feeling progressively sicker as

each day went past. I continued to go on every patrol and perform full duty,

such as the posting of the guard for General MacArthur but it was not easy.

Everything I ate came back up as soon as it him my stomach. The best thing I was

able to find was canned green peas. Those went down and stayed there for a few

minutes before coming back.

Finally, I went in to see our Battalion Surgeon and told him I didn't feel well.

I was wearing sunglasses to protect against the tropic sun glare. The Doctor

took a look at me and reached for an evacuation slip. He said, “You have

hepatitis, I can see the yellow of your eyes even through the glasses". I said

"Oh, you mean yellow jaundice?" He blew a fuse and informed me that "jaundice"

means yellow, so when someone says "yellow jaundice" all he is saying is

"yellow, yellow.” That bit of information stuck with me ever since and I find

myself correcting others when they talk of "yellow jaundice." At any rate I was

taken by barge from Bottomside to an airstrip at

Mariveles,

on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula. There the pilot of an L-5 flew me to San

Fernando in Pampanga Province, at the north end of Manila Bay. I spent

about a week in a makeshift hospital there recovering before making my way back

to duty.

|