The

Ship That Couldn't Sink

Serving on the "Concrete

Battleship"

By Carolyn Younger

Staff Writer, St. Helena Star.

More than 60 years

ago Calistogan Jack Cole served aboard the USS 'No Go' the army's only

"battleship" in the Pacific Theater during World War II or any theater of war

for that matter. Known officially as Fort Drum, it was originally a coral island

at the entrance to Manila Bay in the Philippines. Called El Fraile, it had

Spanish fortifications set up in 1898. Between 1909 and 1919 the island was cut

down by Americans forces and covered in a concrete shell made to resemble a

ship.

Fort Drum, part of the Army's network of harbor defenses of Manila and Subic bays, was considered impregnable. But with the fall of Bataan and nearby

Corregidor on May 6, 1942, Cole, and other members of Battery E 59th Coastal

Artillery, learned otherwise. "If we'd had water we could have lasted three or

four years --we had the food," Cole said as he recalled the days before he and

the 428 men were taken prisoner.

"See all the water that came in was brought on

water tenders from Caballo Island. Without water we were done for. We had water

all around but none we could drink."

Cole, 82, a longtime

Calistoga hairdresser and antiques dealer, sports three tattoos, two of them

nearly 70 years old. He's a little hazy on their origins but he thinks the

unicorn was done at a state fair in Indiana when he was just barely in his

teens and living with his grandparents. Another, a heart with the word "Mother,"

stems from the time he ran away to Los Angeles at 13 "to see the wild west."

Instead he spent the night playing checkers with the desk sergeant in a Glendale

police station before being sent home. The third and newest of the lot is a

sentimental depiction of a dark-haired girl in a polka dot scarf, a tattoo he

got while stationed in the Philippines.

And then there are the war memories. He

signed up in 1939 and when the U.S. entered the war, he was stationed at Fort

Drum, more commonly called "the concrete battleship."

"The first time I got

there was at night and you could hear the diesel motors," Cole recalled. "You

would swear you were on a ship. Everything was designed like on a ship." There

was even a 60-foot fire control cage mast used to direct missiles. "I was spotting planes on the middle of

it one time with missiles going right past me," Cole said. "I was lucky. A

missile dropped on the deck about 30 feet from me and I couldn't hear for about

two days."

The distance of six decades has tempered

Cole's wartime memories and added spice to the telling of otherwise horrific

adventures.

Fort Drum, 350 feet long, 144 feet wide with a top deck 40 feet

above low water, had exterior walls 25 feet to 36 feet thick. It was Cole's home

for nearly three years. During the six-month siege, from December 1941 to May

1942, Corregidor — whose guns were being used to support Filipino and American

forces on Bataan — was hit with more than 16,000 rounds in one 24-hour period

before its fall. Enemy guns were also pounding away at Fort Drum, knocking at

least 15 feet of concrete off the decks. "Towards the end there, the whole

structure would shake," Cole recalled.

Fort Drum, 350 feet long, 144 feet wide with a top deck 40 feet

above low water, had exterior walls 25 feet to 36 feet thick. It was Cole's home

for nearly three years. During the six-month siege, from December 1941 to May

1942, Corregidor — whose guns were being used to support Filipino and American

forces on Bataan — was hit with more than 16,000 rounds in one 24-hour period

before its fall. Enemy guns were also pounding away at Fort Drum, knocking at

least 15 feet of concrete off the decks. "Towards the end there, the whole

structure would shake," Cole recalled.

The end came May 6, 1942, at noon. On

the commander's order, the concrete battleship was flooded, the guns drained of

recoil oil and fired one last time, the colors lowered and burned. Members of

the 59th were either killed, missing in action, or taken prisoner. "I heard

there were 428 of us taken," Cole said. "As far as I know just 28 of us

returned."

Cole and the remaining members of the 59th were taken in fishing

boats to the Cavite side of Luzon and from there to Cabanatuan prison camp where

men were dying daily from malnutrition, malaria and dysentery.

"People ask me

why I didn't try to escape," Cole said. "It was impossible. On one side was a

Japanese military installation. On the other, unchartered territory. Even the

Japanese wouldn't go in there, so where were you going to go even if you did

escape?"

At Cabanatuan, Cole and other prisoners

worked in the fields planting casaba roots and Japanese sweet potatoes. "We ate

the vines, they ate the casabas. We'd eat them raw when we got the chance but it

was dangerous because they used night soil for fertilizer." Food was foremost in their thoughts —

its scarcity, and how and where to get it. Cole remembers eating the branches of

papaya trees, trimmed of bark and sliced. And eating python. "Six of us captured a python about 16

feet long," he said. "The Japanese let us take it to camp. So we carried it four

or five miles. We ate it. It was good — the python tastes more like chicken, and

we craved protein." "I'd eat anything that didn't eat me first," Cole explained,

"except rats."

It didn't pay to be squeamish, he said.

"Some guys said they wouldn't eat rice because it had rice worms. Now a rice

worm is a mournful looking thing, but I ate it all."

After two and a half years, Cole was

sent with others on a prison ship to Japan. Three hundred men or more were lined

up in the hold with only a bamboo slop bucket for a toilet, he recalled. "They

let us out every so many hours and rinsed us off with salt water but the smell

was awful. The only issue on the ship was coconuts and garlic and most of us had

dysentery. That was something."

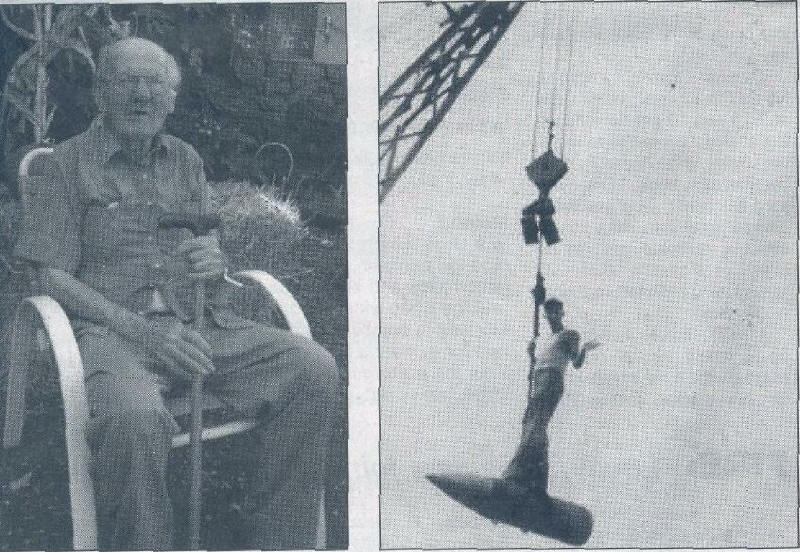

The

fort's "cage mast," a tower used to direct shell

fire. The top of the mast was approximately 89 feet

from the deck Contained various range finders

Cole worked forced labor in a steel mill

between Yokohama and Tokyo then was moved to a copper mine near Hondo. He and

his fellow prisoners knew the war had ended when Navy planes began flying over

and dipping their wings. Later, planes dropped 50-gallon drums of food. The

first drum he came across was filled with chocolate bars and fruit cocktail.

"For a long time I hated chocolate," he

recalled. "I ate so much I was sicker than a dog ... I hadn't had chocolate for

years and the fruit cocktail didn't help."

Looking back, Cole doesn't dwell on why

he survived when others didn't. But he does think about the war — although he

knows that he's losing bits and pieces of those times — and sometimes he dreams

he is back in the prison camp. "We had to live by our wits," he said.

"If I didn't live by my wits I wouldn't have made it.

"But," he added,

"I guess my time wasn't up. I always say, 'I'll live 'til I die.