|

REMINISCENCES

OF THE BATTLE OF MANILA

February 3 - March 3, 1945

by

James Litton

___________________________________

The Battle of Manila was the only urban battle waged by the American Armed

Forces in the Pacific during World War II.

In the evening of February 3, 1945, American motorized units, with

the aid of Filipino guerillas, stormed the gates of the University of

Santo Tomas (UST) to liberate American and other civilian allies interned

there from around the start of the Japanese occupation of Manila on

January 2, 1942. The first

American air raid over Manila on September 21, 1944, was the prologue to

the forthcoming battle that would bring about the destruction of the city

that we all then fondly and proudly called the Pearl of the Orient.

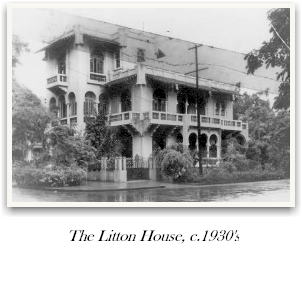

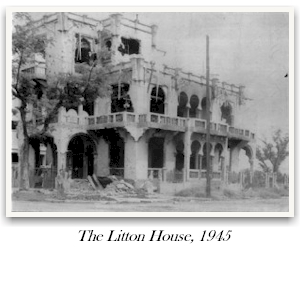

Since 1936, my family had lived in Ermita in a house located in the

corner of Isaac Peral (now U. N. Avenue) and Florida (now M. Orosa)

Streets. My father, George

Litton, Sr., had bought this house from the Spanish Moreta family. It was

a beautiful three storey Moorish styled edifice with arches, balconies,

and a roof garden. The Florida Street side of the house faced the

Episcopalian Cathedral of St. Mary and St. John on whose site now stands

the Manila Pavilion Hotel.

Ermita was a quaint, distinct, and idyllic residential area. It had

a character of its own, different from that of Malate, Paco, or Pasay. It

was, in the words of Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, “[A] charming colonial town

built by Europeans and Americans….” Many Spanish families lived in Ermita

as did other expatriates. It was common to read a doctor’s shingle hanging

outside his office describing the medical practitioner in Spanish as a

“Medico-Cirujano” and signs of “Cuidado por los Perros” hung on the gates

of houses so as to warn passers-by that the house was guarded by fierce

dogs. Isaac Peral Street was by far the most beautiful street in Manila.

Both sides of the street were bordered by wide clean sidewalks and giant

Acacia trees whose arching branches formed a tunnel like bower extending

from Taft Avenue up to Dewey Boulevard (now Roxas Boulevard).

I had turned eleven in June of 1944. We were then in the middle of

the third year of the Japanese occupation and I was no longer attending

school. I did return to La Salle as soon as it had re-opened in 1942,

after briefly attending classes at St. Paul in Herran Street (now Pedro

Gil). I had to leave La Salle after I had finished the third grade because

transportation was getting very difficult. No cars were running as

gasoline was not available. I would go to La Salle to attend my classes by

taking the tranvia [streetcar] from San Marcelino Street but even that had

become very difficult as the tranvias had become always jam-packed.

Passengers would hang by the windows or even climb up the roof of the

tranvias just to get a ride. My mother transferred me to Santa Teresa in

San Marcelino Street, a girl’s school run by Belgian nuns that accepted

boys up to the fifth grade. Santa Teresa was just a fifteen minute walk

from our house. In May or June of 1944, however, the Japanese military

took over the premises of Santa Teresa and thus I no longer had a school

to go to.

Nuns and Members of the Japanese Army in Manila

In the early morning of September 21, 1944, I went to Wallace

Field to meet my close friend Henry Chu. Wallace Field was the site of

the famous annual Manila Carnival. It is now part of the eastern section

of Rizal Park. Henry Chu

lived in San Luis Street (now T, M. Kalaw) at the Queens Hotel (a

precursor to our present motels), which was owned and managed by his

father. Our carefree morning was suddenly interrupted by what, at first,

we thought were airplanes in practice maneuvers. We suddenly realized

that there was something terribly wrong when one plane burst into flames

and tracer bullets began to lace the clear Manila sky. I stood in awe,

seemingly unmindful of the danger, as I fixed my gaze upon a single

engine plane descending very fast, almost at an angle of 90 degrees, and

releasing its bombs at a Japanese ship docked at the South Harbor. My

friend Henry grabbed my arm and pulled me as we both ran to his father’s

hotel and into an improvised air raid shelter dug at the ground floor.

There were many more air raids after the first one in September 21.

As soon as we would hear the air raid siren announcing an imminent attack,

my brothers and I would rush to our roof garden to get a ring side-view of

the drama unfolding before our eyes. The air raids became more frequent

around the end of October. By then, we had almost daily air raids by

American dive bombers and later by a new American fighter-bomber, which we

later learned to be the P-38. This fighter-bomber had two engines, one on

each of its two separate fuselages, both of which were connected to each

other in the middle by the cockpit

The skies, during and after an air raid, would be darkened by the

mushroom-like puffs of exploding anti-aircraft shells aimed at the raiding

airplanes. These shells would rain the ground with deadly shrapnel, which

we kids would collect and keep. Around this time, there occurred two

tragic incidents that I still clearly remember.

It was, as I recall, around the first week of November when early

in the morning American dive bombers again flew over Manila.

As we watched American airplanes swooping over Japanese ships

anchored in Manila bay, amidst a maze of tracer bullets and bursts of

anti-aircraft shells, we heard the groaning sound of an American dive

bomber coming towards us from the east. The sound of its engine indicated

that it was in trouble. As we watched this plane flying low and heading

west towards us, we were horrified to see that it had jettisoned its load

of a single bomb, which began its descent directly towards us! We all

thought the bomb would hit us but it passed overhead and ended its deadly

descent in a loud horrifying explosion, shaking our house and the ground

beneath us. We later learned that the jettisoned bomb had hit the house of

Dr. Luis Guerrero, in Isaac Peral Street, just a few blocks from our

house. Carmen Guerrero Nakpil, in her book Myself, Elsewhere, wrote:

“Three houses in the block that we Guerreros shared were rubble and two

more were severely damaged. Tio Luis’ son, Dr. Luisito … and the three

maiden aunts, Liling, Felisa, and Neng were killed.”

I remember the date well. It was in the morning of January 8, 1945,

when we heard the air raid siren announcing another air raid. From the

roof garden of our house, we were greeted by the magnificent sight of a

squadron of American four engine bombers flying from the west at a

relatively low altitude. We could clearly see its four engines and its

twin rear tail. (We would later learn that these were B-24s Liberators).

The Japanese anti-aircraft barrage started and the sky was soon

pock-marked by its black puffs marking where the shells had exploded.

Frank Stagner, a twelve year old American interned at the University of

Santo Tomas (UST), was also looking at this squadron of American bombers

and he recalls that:

“My younger 10 year old brother Lawrence and I were crouched under

our shanty and could hear the roar of the approaching Bomb Group and the

loud cracks of the bursting enemy AA. Like a couple of nit wits, we stood

outside and in awe of the approaching B-24 Bombers with the puffs of the

airbursts all about the flight. I definitely observed a flash and AA burst

under a trailing bomber. A tiny red glow was then observed under the

bomber and began generating a long slender trail of brown smoke. As the

B-24s neared, the flames began to grow much larger and with a thicker

trail of smoke. Shortly after the stricken bomber passed, it suddenly went

into a sudden dive to the right and away from the Group formation. I

witnessed and felt a horrendous explosion where the B-24 should have been.

I was able to observe only three men with chutes. One was at a much higher

altitude with what I considered a normally opened one. This man was

rapidly drifting back to the target area.”

What Frank Stagner did not see was that one of the crew that had

bailed out had fallen and drifted towards Ermita and the bay. From our

roof garden perch, we could clearly see this hapless American dangling

from his chute as it descended and drifted towards Dewey Boulevard. When

the chute was nearly overhead and the man strapped to it was clearly

visible, we suddenly heard a series of gunshots. The Japanese were

shooting this completely helpless man dangling on a parachute! The

barbarity of this incident was shocking even to an eleven year old boy!

Many years later, after the war had ended, I would learn the fate of the

crew of this unfortunate B-24 from Sascha Jean Jansen, nee Weinzheimer, an

American friend, interned in the UST, and daughter of the former owner of

the Canlubang Sugar Estate.

Go to Page 2

|