|

Around the middle of December, 1944, Japanese marines began to erect

obstructions in many of the streets of Ermita. Concrete barriers, strewn

with interlacing barbed wires, were placed along these streets, some of

which were also sowed with

deadly land mines and aerial bombs buried with their fuses protruding

slightly above the surface of the street. Pill boxes were built in a hurry

in certain strategic places. Our house was a corner house and its fence

had an ornate iron railing embedded atop a concrete base that was about a

meter or so in height. The

Japanese entered our house and constructed an elaborate pill box at the

corner where two rectangular openings were chiseled out the fence’s

concrete base and through which were positioned two clip fed high caliber

guns. The guns commanded a wide expanse of the eastern length of Isaac

Peral and the southern approach to Florida Streets. The soldiers also dug

a trench from the pill box leading directly to the crawl space under our

house. Many pre-war Manila houses, especially those built of concrete, had

its first floor constructed about a meter or so above the ground, thus

creating crawl space between the ground and the first floor. Diagonally

across the pill box was the campus of the University of the Philippines

(UP) and on its eastern side, the Episcopalian Cathedral, both of which

had been commandeered and occupied by the Japanese. Sentries were posted

on the eastern corners of Isaac Peral Street but the Japanese soldiers

manning these posts did not carry guns but were only armed, amazingly,

with a spear made from a long

wooden pole to which was attached a sharp blade.

I remember that February 3, 1945, was a Saturday because my father told me

not to hear Mass the next day at the Ermita Church as it now seemed too

dangerous to be walking about the streets. Early in the evening of the

same day, my father received a telephone call from a relative who lived in

the Santa Cruz district of Manila. The message was short but direct to the

point: “The Americans were now in the northern part of Manila!” Shortly

after this call, all telephone communication was cut off. About

mid-afternoon of Sunday, February 4, we heard several extremely loud

explosions north of where we were. My father thought aloud and said that

the Japanese must be blowing up the bridges that spanned the Pasig River.

He was right. Electricity and water supply had been cut off even earlier.

My mother had the foresight of collecting potable water in several

demijohns. She also had an artesian well dug in our yard but the water

that was pumped out was salty as we were very near Manila Bay.

On February 5 or 6, a Piper Cub, a single engine American observatory

plane, flew over Ermita and Malate and dropped leaflets. One, I recall,

announced that General MacArthur had landed in Leyte earlier in October of

1944. We got a good look at this Piper Cub as it flew over us at a rather

low altitude. What struck most of us as odd was the insignia on the plane.

We remembered that the insignia on American airplanes was a big white star

with a red ball in the middle. The insignia on the Piper Cub was a white

star with two wide white strips on each side.

No sooner had the Piper Cub left than the American shelling began. To be

in the receiving end of an incoming shell is about the most frightful

experience one can ever live through.

An incoming shell sounds very much like a speeding freight train

coming straight at you. Because of the Doppler effect, the pitch of its

screech gets higher and higher as it nears you, if you are, or if you are

near, its intended target. A shell hit the Prince Hotel, which was just at

the back of our house, severely wounding Mr. Wing, its Chinese proprietor.

We were shelled daily. The shelling at night was even more frightful as we

were in total darkness. The house of Dr. Rafael Moreta, our immediate

neighbor, was hit by a shell in the evening of February 8. My mother

invited the Moreta family to come to our house as our house was more

strongly built and the Moretas were all cramped in an air raid shelter in

their yard.

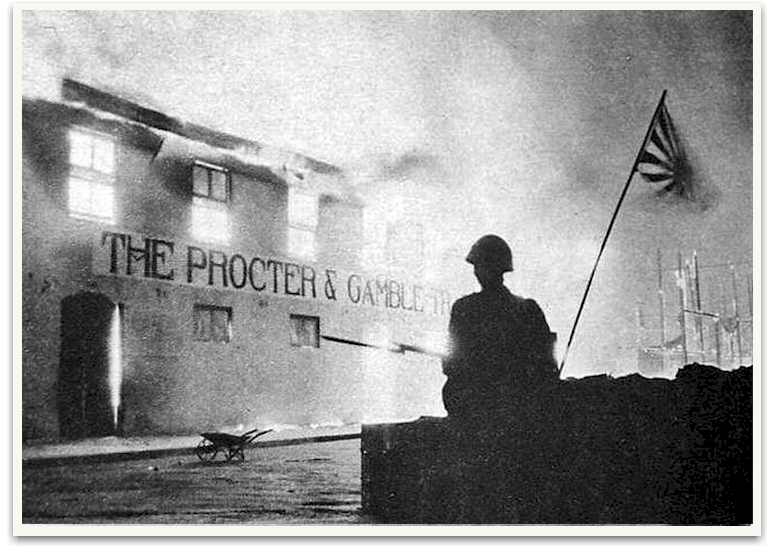

The darkness of night on February 9 was suddenly lifted by the glow of

raging fires that broke out all over Ermita. It seemed that the Japanese

were setting fire to the houses in our neighborhood. Except for the

Episcopalian Church and the buildings in the UP campus (both of which were

occupied by the Japanese), fires raged all around us. My cousin Anselmo

Salang was attempting to tear down the sawali matting [woven strips of

split bamboo used for partitions] that hung on the fence separating our

house from the Prince Hotel, when a Japanese soldier, standing on the

steps of the Episcopalian Cathedral drew a bead on him and shot him,

narrowly missing his head by just a foot. Civilians, whose homes were on

fire, came streaming to our house to seek shelter. By around midnight of

February 9, there were about 120 people huddled in the ground floor of our

home.

They set the fires, and shot anyone seen

fleeing the burning buildings.

In the morning of February 10, a Japanese officer came to our house and

told us that we all had to leave in an hour’s time. We quickly packed

small packages of whatever food we could gather, but in less than half an

hour, a squad of fully armed Japanese marines came to our house and

mounted a machine gun pointed at our front entrance. We were told to leave

immediately. The elders in

our house had earlier decided to seek refuge at the Ateneo University or

at the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) at Padre Faura Street. As we

streamed out of the main entrance of our home, the Japanese soldiers began

rummaging through our belongings, opening bags, and helping themselves to

whatever they found. I clearly remember one Japanese marine taking a wad

of Japanese wartime peso notes from the handbag of an elderly lady as if

there were still any place where he could have spent such useless paper

bills! I now realize that the Japanese did not kill all of us, all 120 or

so of us, because it would have been too much trouble getting rid or

burying so many dead bodies. They were anxious to get into our house to

feast on whatever they would find inside.

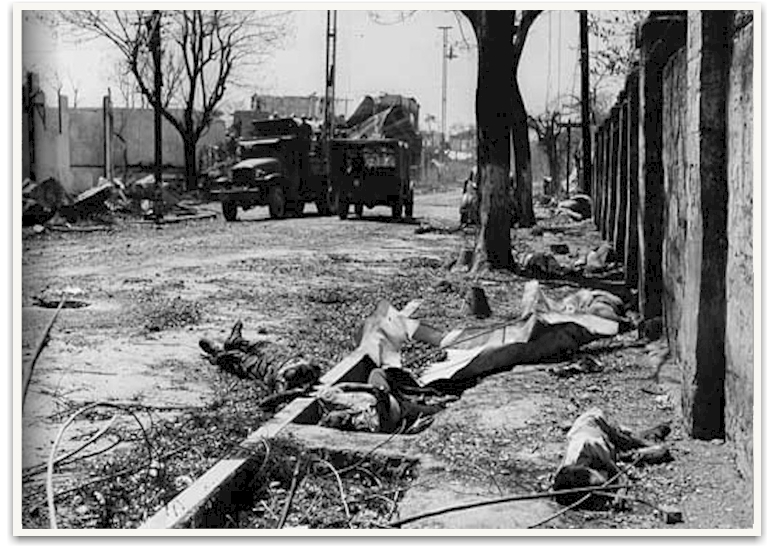

The only way from our house in Isaac Peral to the PGH or the Ateneo was

through Florida Street. Those who came out of our house first, walked

ahead of the rest that came later. I remember walking on Florida Street

towards Padre Faura Street with my elder brother George, Jr. to my left.

My mother was slightly ahead of me and to my right. To my left also and

about four meters ahead of me, carrying a basket on her head, was fifteen

year old Leonarda “Narda” Pangan, a native of Dinalupihan, Bataan, my

mother’s hometown. Florida Street was strewn with debris. The buildings

along its side across the UP campus were all razed by the fires that raged

the night before. Florida Hall, the boarding house for the female students

of the UP, was just a pile of smoking rubble as were the other buildings

along the whole length of Florida Street. We were nearing Arkansas Street

(now Engracia C. Reyes), which ran directly perpendicular to the entrance

of the UP College of Engineering, now the Court of Appeals, when my mind

began to wander a bit as I recalled that it was at this very same spot

where, a year or so ago, the Japanese sentry posted at the gate leading to

the building of the College of Engineering shouted at me with a shrill

Kura Kura! as I passed him on the other side of the street. I knew

immediately that I had failed to stop and to bow before I passed him. I

quickly retraced my steps, stood in front of the sentry, and bowed bending

from my waist. I may have gotten off easy as the sentry did not command me

to come forward to be slapped but just waved me on after I had bowed.

My bit of day-dreaming was suddenly interrupted by a horrendous and

ear-splitting explosion ahead of me and to my left. I glanced to my left

and saw my elder brother George Jr. standing with both hands covering his

face. About two meters in front of him, lay the legless torso of a woman

with long black hair, whose left arm was also amputated up to the

shoulder. She lay moaning,

blood flowing from the stump of her lower torso. My mind was in a daze and

my ears were ringing but I soon realized that this hapless woman was the

fifteen year old Narda. She had stepped on an anti-personnel land mine! As

I gazed to my right, I saw my mother lying on the ground on her right

side, all bloodied and motionless. I rushed to her side as I called to her

but I received no response. Suddenly, someone shouted “Run, save

yourselves!” Many in our

group just dropped whatever they were carrying and ran towards Padre Faura

Street. Anselmo Salang, my cousin, heroically took it upon himself to

carry my mother, as we all madly rushed towards Padre Faura Street and

into the PGH. Slowly, we found each member of our family in the interior

court yard of the PGH. Doctors attended to my mother as best as they could

and she was placed on a bed in a ward on the second floor of the hospital

facing Taft Avenue. My brother George, Jr., blinded by the land mine

blast, was placed on a bed at another ward. The rest of us, including

Robert Reyes, my seven month old first cousin being cared for by my

maternal grandmother, sought shelter at the Nurses’ Home, a two-story

building on the corner of Taft Avenue and Padre Faura Street, which served

as dormitory for the nurses on duty. The mangled body of poor Narda was

left where it lay on Florida Street.

Go to Page 3

|