|

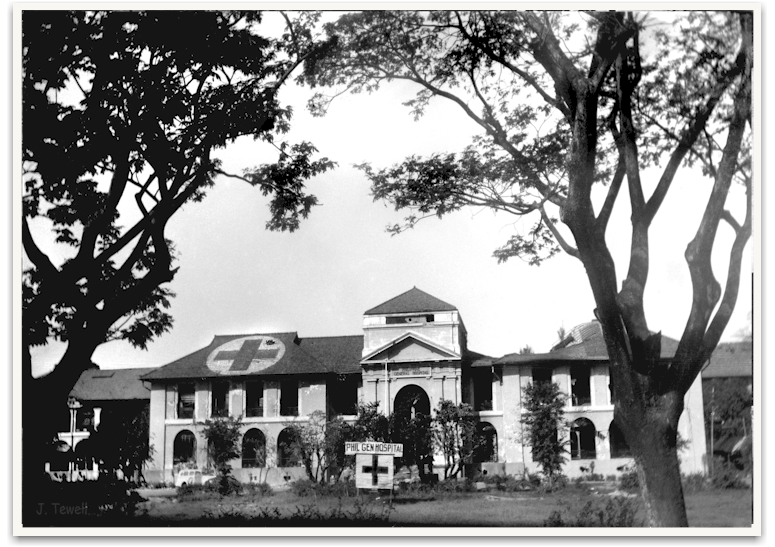

The Philippine General Hospital (PGH)

I spent the night of February 10 -11 in a walk-in closet in a bathroom at

the Nurses’ Home. Dolly Moreta, who was also with us, had suggested that

we all stay inside the bathroom as it seemed to be the safest place as its

walls and floors were of concrete.

We had lost almost all the food we were carrying when pandemonium

reigned and everybody dropped whatever they were carrying after the

explosion of the land mine that killed Narda.

My baby cousin Robert was crying the whole night as he must have

been both hungry and thirsty. We were all hungry but being thirsty was

more, very much more oppressive. Thirst, extreme thirst, is like a feral

spirit caged in one’s throat, demanding to be assuaged, demanding one’s

full attention, and never letting up until it is satisfied. By around 3 in

the morning, my cousin Anselmo came with some water in a tin can that had

once held some peaches. I could still see the label on the tin. The water

tasted stale and of rust but I took my share of two big gulps. Later, I

learned that my cousin Anselmo had taken this water from the water tank of

one of the flush toilets!

Early in the morning of the next day, a Japanese officer came to the

Nurses’s Home and ordered all of us to leave. I no longer remember how we

got to where we went, but my family, less some members who were attending

to my wounded mother and brother, ended up on the second floor of the

South Wing of the PGH, in a room full of bottled specimens of human

internal organs. From the window, I could see the Bureau of Science

Building, then situated in the corner of Taft Avenue and Herran Street

(now Pedro Gil) and just about fifty meters from where I stood, I could

also see an artesian well, with its long wooden lever being pumped for

water by those who dared make the perilous trip, taking a chance on not

being hit by American shells or shot at by Japanese snipers, from the

Bureau of Science building, who all took delight in shooting innocent

civilians.

We stayed in this room full of specimens of human internal organs for

three whole days. We had no food and again no water. On the third day

without food, my mind wandered, and I began to imagine that one of the

bottled specimens began to look very much like a leg of ham! Hunger can be

debilitating but it can lull you to sleep. Not so with thirst. The craving

for water was overpowering and maddening!

My mother was in a bed at a ward

facing Taft Avenue on the same second floor where I was. My elder sister

Emma brought me to my mother’s side. She was bandaged, her left arm in a

cast, her face blackened by burns. She was in pain and moaning. The whole

ward smelled of rotting flesh and of death.

My father, who was an inveterate

smoker, was beside my mother when I visited her in her sick bed.

I was surprised to see him smoking. It seemed that among the few

packages that were saved during that mad rush to the PGH was one which

contained a can of Lucky Strikes (cigarettes before the war could be

bought in cans). A young man, I think he was a Chinese-Filipino, who was,

as it turns out an inveterate smoker himself, saw my father smoking and

unhesitatingly struck a deal with him. This young man said he would fetch

water for us from the artesian well in exchange for cigarettes. Two

bottles of water for one cigarette! The power of addiction to nicotine

thus secured for me my first drink of water in two days!

Shelling became more intense as the Americans fought their way nearer to

where we were. My elder brother and my father were all afraid that the

second floor of the PGH did not afford sufficient protection against a

shelling barrage. We all needed to go to a safer place to hide.

It was one of those chance meetings that changed and saved our lives. My

elder brother Edward was staying with my wounded brother George, Jr., at

another PGH ward. I don’t know the circumstance surrounding the event, but

there my brother Edward met Andrew “Andy” Cang, businessman from Cebu,

whose family was in Manila, and who had been bringing copra by batel [a

small sail boat] to sell in Manila.

Mr. Cang was also a guerilla, wanted by the Kempeitai [Japanese

Military Police]. He and his family sought refuge in the PGH when the

Japanese began to set Ermita on fire. And like my brother, he too was

concerned for the safety of

his family from American shelling. I don’t know whose idea it was, but

together my brother Edward and Mr. Cang decided to move the members of

their families to the anteroom of the elevator shaft that was situated on

the basement floor near the main Taft Avenue entrance of the PGH. One can

enter the ante-room of the elevator shaft only from the courtyard behind

the main building. There was a small entrance and stairs of about six

steps that went down to the basement floor, which was about two meters

below the hospital ground floor and had a floor area of around thirty

square meters. The Cang family

had moved in first. Thereafter, my brother Edward carried my mother and my

wounded brother to this newly found haven of relative safety. He then

collected the rest of us and brought us to the ante-room of the elevator

shaft. As soon as I stepped down into the darkened ante-room, Mrs.

Remedios Cang (bless her kind heart!) met me and gave me half-cup of

cooked rice with tausi [black salted Chinese beans].

This was, and forever will be, the best meal I have ever, and will

ever have, in my whole life!

I no longer recall how many days we stayed in the ante-room of the

elevator shaft. It was always dark inside except for the little light that

shone through the small entrance. More people joined us and the space

became a bit cramped. There was, about a meter above the basement floor of

the elevator shaft, a rectangular opening, big enough for a man to go

through, that led to the crawl space of the hospital. Many of us made

ourselves as comfortable as we could inside this crawl space. Mrs.

Remedios Cang provided us with as much food as she could share, and some

of the young men with us dared to go out to the artesian well to get

water. American shells were coming in at closer intervals. From a peep

hole in the crawl space, we could see American tanks on Taft Avenue as

fierce fire fights were taking place at the dispensary building near the

southern wing of the hospital.

The

Japanese showed us no mercy and no humanity.

It was the morning of the 17th of February, a date I shall never forget.

There was incessant shelling in the morning. Mortar shells, recognizable

by the multiple fins on its tail, rained on the PGH. American tanks even

fired rounds directly at some sections of the hospital. Suddenly, just

before noon, there was an eerie silence. I thought I first heard it as a

low murmur coming from outside our basement hide-out. Then it became

louder, a loud hysterical roar as people were shouting “Amerikano!

Amerikano!” The Americans had

arrived at the PGH! I peeked out of the entrance of our basement hide-out

and I saw a tall soldier, a white man, leaning against the railing. I was

a bit confounded as I could not readily believe that this soldier, who was

just a meter away from me, was an American. He wore a different type

helmet, not like the soup plate helmet of Bataan vintage, his uniform was

not khaki but one made from olive drab herringbone twill; he wore shoes

that had a narrow strap that reached above his ankles, and he carried a

gun the likes of which none of us had ever seen before. (Later, I found

out that he was carrying a magazine fed carbine.) The joy I felt upon

realizing that we had at last been liberated was indescribable. I was

ecstatic, happiness was bursting from my chest, realizing that I had

survived and that my whole family had survived as well although my mother

was seriously injured.

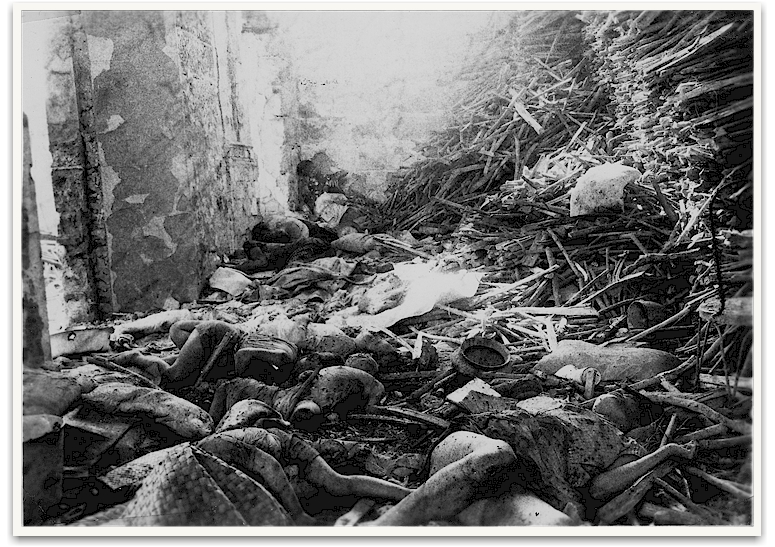

By all measures of human consideration, ALL the death and destruction

in Manila was the direct and intended and consequence of a deliberate

Japanese decision.

U.S. Army ambulances arrived at the PGH and took the more seriously

wounded. My mother was loaded on an ambulance together with several other

injured civilians. My brother Edward, who was then a medical student,

wanted to go with my mother but he was not allowed by the American

ambulance crew. We were not told where the ambulance was taking all the

wounded. We would not know until about two weeks later that my mother was

brought to the San Lazaro Hospital in Santa Cruz, Manila.

The rest of us prepared to leave the hospital in a hurry as there was a

rumor that the Japanese might launch a counter-attack. They still held

many of the UP buildings along Padre Faura Street, which were just a few

buildings north of the PGH. There began an exodus of civilians from the

hospital numbering in the thousands.

We left as a group but later on got separated again. As we left the

hospital, I saw the body of a recently killed Japanese soldier lying near

the main entrance. There was utter destruction everywhere. There wasn’t a

single building on Taft Avenue that I could see that was not razed by fire

or by shelling. We proceeded along Oregon Street (now G. Apacible), not

knowing where we should go. Because of the number of people on Oregon

Street trying to get as far away as possible from the recently liberated

PGH, our family got separated. I was with my brother George, Jr., who had

by now recovered his eyesight, and my maternal grandmother who was

carrying Robert Reyes, my seven month old cousin. I recall walking until

we reached a small bridge on the left side of which were the remains of a

public school. My baby cousin was crying intensely as he must have been

very thirsty as we all were. I hesitated at first but I went straight to

an American soldier who appeared to me to be an officer and asked him if

he could give us some water from his canteen. Unhesitatingly, he took out

his canteen and handed it over to me.

I shall never forget the kindness of this man.

Somehow, we found each other, and the whole family, with the exception of

my mother, was whole again. We sought shelter at an abandoned house along

General Luna Street and stayed there for two nights. We were still very

near the front lines. Monstrous Sherman tanks, jeeps with mounted machine

guns, and half-tracks with mounted howitzers were rumbling along the

streets day and night. It was here where I met a GI named Salves.

(I cannot recall his first name.) He was from New Hartford,

Connecticut. One morning, while we were talking with him, we heard the

frightful screech of an artillery shell above us.

We all dove to the ground for cover while Salves just stood and

laughed at us! He told us not be scared as that shell was an “out-going.”

He could tell an “out-going” shell from an “in-coming” shell from the

pitch of its whizzing sound. An “incoming” shell has an ascending pitch

while that of an “out-going” shell has a descending pitch. After two

nights in our temporary refuge, my father decided that we should try to go

to Santa Cruz as he had a house there in Calle O’Donnell (now Severino

Reyes). We heard that we could

cross the Pasig River at Pandacan. Early in the morning of February 20, we

set out on foot for the southern bank of the Pasig River at Pandacan by

first walking the length of Oregon Street until we hit the Paco railroad

station. The station was still there, pockmarked with shell and bullet

holes, but it still stood majestically, built as it was along classical

lines, with a portico and a series of Roman columns below an entablature.

We turned left and walked for about two hours more until we reached

the southern bank of the Pasig River at Pandacan where now stands the

Nagtahan Bridge. There was no bridge there then and I thought we would

have to cross the Pasig River by banca (a wooden boat) but it turned out

that there was in fact a bridge, an odd looking bridge at that, made out

of inflated rubber rafts placed side by side until it reached the opposite

bank of the river. On its surface were placed two parallel perforated

steel planks, each about a meter wide and about a meter and a half apart.

I later learned that this amazing bridge, built by the US Army Corps of

Engineers, was called a pontoon bridge. It could carry human traffic as

well as light vehicles. Upon crossing this pontoon bridge, we walked along

Calle Nagtahan until we reached the Carriedo Rotonda. We then proceeded

along Legarda Street, turned right on Azcarraga Avenue (now Recto Avenue)

right on Avenida Rizal, and then left on Zurbaran Street, which ran

perpendicular to Calle O’Donnell.

|