|

d. Demolitions:

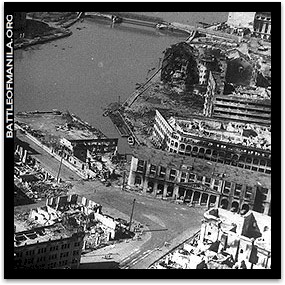

Demolitions played an important part in the defense of the city, inasmuch

as they were used to great effect in destroying bridges prior to our entry

and in demolishing sections of buildings after occupation.

Evidence of prior planning of bridge demolition is contained in the

following extract:

"Manila Defense Op Order A No. 1. (Shimbu Gp)

Santa

Mesa

Defense Force Order

2300, 3

Jan 45

"6. Manila Detachment will firmly occupy the key

points in the city. Thus it will endeavor to annihilate the enemy airborne

forces and thus decrease his fighting strength, and simultaneously the

Detachment will take charge of preparations for protection and destruction

of Main installations, especially bridges, in the city.

"At key points of traffic, particularly at

bridges, the Detachment will check the north and south movements of enemy

armored cars. The area of the line connecting west of Novaliches

(included), Meycauayan and the lower reaches of the Meycauayan River at

Meycauayan, and that north of small stream to north of Manila will be

newly added to the combat area of Manila Detachment.

"8. South Flank Detachment Commander will be

responsible for the protection and destruction of Pasig Bridges with a

portion of one Infantry Company which has been dispatched to the vicinity

of Sakura Barracks and with the forces mentioned in the foregoing

paragraph."

Of a total of about 101 bridges in the city of

Manila and immediate environs, thirty-nine, were destroyed. The most vital

bridges, as far as the tactical situation was concerned, were the six

bridges over the Pasig River joining the northern and southern sections of

the city. All of these were destroyed. In the section north of the Pasig

River, there was a total of fifty-eight bridges, of which nineteen were

destroyed.

In the section south of the Pasig River there were

thirty-seven bridges; twenty destroyed. The greater percentage of

destroyed bridges south of the Pasig River may be explained by the fact

that the enemy withdrew toward the south and consequently had more time

for demolition work in this section.

As a general rule, the bridges destroyed were from

one hundred to four hundred feet long, while those left intact were much

shorter and never exceeded seventy feet in length.

Except for certain bridges over the Pasig River,

all bridges in the city were blown prior to the entry of our troops. Those

over the Pasig were destroyed about the time our troops reached the north

bank of the river. The precise time of demolition of those destroyed prior

to our entry is not known, but it was probably 3 February, as implied by

the following captured order:

Manila Naval Defense Force Op Order No. 44

3 Feb 45

Manila Naval Defense Force Comdr Iwabuchi, Mitsuji

"1. The North and South Forces will immediately

destroy all bridges in the suburbs with the exception of Novaliches

Bridge, (The Kobayashi Gp (Heidan) will be responsible for the Marikina

and Pasig Bridges) 33 (MA) (San Juan) Bridge and the five large' bridges

(1 (1),2 (RO), 3 (HA), 4 (NI), 5 (HO) ) over the Pasig River.

As to the demolition of the above mentioned

bridges and of various small bridges in the vicinity of the principal zone

of city, special orders will be given. However, the time of demolition

will be about the same time as that for the demolition of the 4 large

bridges.

"2. The demolition must be done completely and

thoroughly. In order to prevent the guerrillas from action to construct

bridges, and to prevent speedy transmission of intelligence and passage

across, several guard personnel will be posted at the completely

demolished principal bridges.

"3. Each unit will quickly report as soon as

the principal bridges are destroyed.”

Practically every important bridge in the city was

destroyed. The relatively few left intact represented very difficult

demolition jobs, a fact which suggests that the enemy lacked sufficient

qualified personnel to undertake them. As a whole, the bridge demolition

work was better executed and destruction more nearly complete in the

Manila area than in the Central Plains of Luzon. Most of the bridge

demolition.in Manila would be considered good by American standards.

Japanese bridge demolition was marked by the

following general characteristcs:

(1) On multiple span bridges, the span on the

Japanese side was usually blown. Other spans in many cases were prepared

for demolition but often remained intact.

(2) In the demolition of concrete slab bridges,

the enemy apparently concentrated on the destruction of the bridge

decking.

(3) Concrete arch type bridges were found blown in

middle sections.

(4) Steel truss bridges were sheared close to the

supports with only abutments and piers left standing.

(5) No bridges of any type were found that had

been prepared for time demolition after our entry.

The only other significant use of demolitions

was encountered during the assault on fortified buildings.

In

many instances our entrance and subsequent occupation of a small section

of a structure were met by controlled blasts affecting only that portion

held by our forces. Usually charges were too light to cause the

destruction intended by the enemy. By this means, however, obstacles were

often created, and re-entry by another route made necessary.

V. WEAPONS AND THEIR EMPLOYMENT

1.

General

The relatively small enemy garrison left for the

defense of Manila proper had a great variety of weapons and ammunition.

Months of preparation made possible systematic adaptation and

improvisation of weapons for ground defense. One captured order, dated 18

December 1944, stated that "the time of decisive battle on Luzon Island is

drawing nearer and nearer", and ordered the rapid execution of combat

plans. Guerrilla reports of that period referred to accelerated defense

preparations, the construction of underground machine shops, the

installation of demolitions in buildings, and the salvaging of war

materials in Manila. A captured undated memorandum, presumably of the

Manila Naval Defense Force, called for the immediate manufacture of

two-wheeled carriages for 25mm and 13mm machine guns, "the wheels to be

found regardless of the circumstances". Another document directed that as

large a quantity of aviation gasoline and bombs as possible be removed

from the suburbs to suitable places within the city so that they might be

used as "weapons of attack or as material for the production of weapons".

Scrap metal was saved, captured U. S. weapons and ammunition were made

ready, and guns were moved from sunken ships and wrecked aircraft.

Ordnance shops were found in Manila, several located in underground

tunnels. In these the enemy had produced ground mounts for aircraft

machine guns, hollow charge lunge mines, grenades, demolitions and

improvised mines. The result was to give the defense force a concentration

of automatic and support weapons out of proportion to its numerical

strength.

Time also permitted some care in the selection and

preparation of sites for all kinds of weapons. Slots for rifles and

machine guns often at knee height were made in the walls of buildings.

Although this arrangement restricted traverse, the apertures afforded

excellent cover of shrewdly selected fields of fire. In the Laloma

Cemetery, three 25mm automatic cannon, hidden in pillboxes camouflaged as

burial mounds, complete with sod, flowers and statues or crosses, were

emplaced for use solely against strategic traffic focal points. In one

confirmed instance an artillery piece was emplaced on an upper floor of a

downtown building, and many antiaircraft guns fired into the streets from

barricaded rooms in upper stories.

While within each center of resistance the fire plans apparently were

charaderistical1y thorough, coordination was lacking in the firing of

weapons during the defense. This was probably attributable in large part

to poor communications and weak overall organization of the miscellaneous

units of the command. Control of the fire of individual weapons was

reported as good, with last-minute ambush fire at point blank range

repeatedly used to good

·effect by enemy riflemen,

machine gunners and anti-tank gunners. The detonation of electrically

controlled mines in buildings was also delayed until the critical moment.

Each weapon was generally so emplaced and protected that, even after

adjacent positions had been overrun, it remained capable of sustained fire

on its original target area until individually rooted out or destroyed.

Except for miscellaneous army units north of the

Pasig River, Japanese naval personnel were charged with the defense of

Manila. In consequence, relatively few army infantry weapons were used.

Some 75mm field guns, a few 47 mm anti-tank guns, standard infantry

machine guns, 81mm and 90mm mortars, and 50mm grenade dischargers were

encountered. In addition, Army 20cm spin-stabilized rockets with Type 4

launchers were employed in negligible quantity.

A prisoner of war confirmed the removal of 12cm

naval guns and anti-aircraft guns from partially submerged ships in Manila

Bay to positions within the city. Aircraft 20mm cannons and anti-aircraft

25mm guns were mounted and emplaced for ground use. On occasion, U. S.

Enfield and M1903 rifles, M1911 pistols, Browning automatic . rifles,

heavy machine guns and cal .50 machine guns were encountered, and a

prisoner verified their use. A few captured M-1 rifles were found on enemy

dead.

Most of the weapons encountered in Manila and

referred to in the following discussion are described and illustrated in

current manuals and bulletins on Japanese weapons. Some of the newer types

are illustrated in the Annexes. (Part Three).

2.

Grenades

Hand

grenades were used extensively during the street and room-to-room fighting

in Manila. Type 91 and type 97 hand grenades, stick grenades and conical

hollow-charge "grass skirt" hand grenades (see

Annex 36) were commonly

employed. Grenades were found near almost every Japanese position.

Molotov cocktails, many with red phosphorus as the

incendiary substance, were found in practically every house and building

that had been occupied by the enemy. It is believed that they were used to

start the many fires the Japanese left in the areas they evacuated. These

incendiaries were also dropped into the streets from windows of buildings

and thrown from room to room and floor to floor. They produced relatively

few casualties but were effective delaying weapons.

Small (1-3 kg) aerial bombs intended for use

against parked aircraft were dropped from the upper stories of buildings

on our troops below and proved effective as hand grenades. Some were found

on the ground with dented noses, indicating that the arming vane had

failed to rotate sufficiently to arm the bombs and permit detonation. -.

Small cakes of explosives were found with a pull

type igniter, a short piece of delay fuse, and two or three blasting caps.

They served as hand grenades and as booby traps. Another improvised

grenade consisted of a 2¾" length of 2" pipe, a blasting cap, a cal. .22

shell (captured U. S.), fuse, and powder. The ends were plugged with soft

scrap metal.

3.

Small Arms

The enemy in Manila made conventional use of

rifles and automatic weapons. Despite frequent mention by our troops of

"snipers," the sniper as a carefully placed individual rifleman

specializing in long-range selective firing seldom made an appearance

(hardly any telescopic rifle sights were found in Manila). Standard

Japanese infantry rifles were not encountered in large numbers, and

quantities of captured U. S. rifles were recovered by our forces still

packed and unused. Because of the high proportion of automatic weapons,

the rifle became a secondary weapon for harassing fire, protection of gun

positions, and personal defense.

4.

Automatic aircraft and anti-aircraft weapons

Aside from the adaptation of aircraft and

anti-aircraft weapons to ground use and the high proportion of automatic

fire thus achieved, there was little out of the ordinary in the employment

of automatic weapons in Manila. Fire of weapons in adjacent positions was

apparently not closely coordinated for surprise or massed effect, although

a formidable volume was often achieved.

The 25mm automatic cannon Model 96, apparently the

basic automatic anti-aircraft weapon of Japanese naval units, was used in

great number in Manila. The majority encountered were of the fixed single

mount variety. These weapons, capable of delivering an estimated 250

rounds per minute, fired HE, HE tracer, and AP ammunition. They were used

throughout the city, a few being emplaced for employment in a dual role

and many for ground fire only.

Twenty mm aircraft machine cannon Model 99, both

fixed and flexible, were frequently converted to ground weapons. They were

undoubtedly removed from some of the many Japanese aircraft destroyed on

the ground by our air strikes. Their great volume of fire was effective in

delaying our forces. The muzzle blast of both the 20mm and the 25mm guns

made them easy to locate, however. At least two 40mm anti-aircraft guns

were also used against our troops in Manila.

The other principal automatic weapons were the

13mm machine gun Model 93, the 7.7mm Lewis machine gun Model 92, and the

7.92mm light Bren-type machine gun. Conventional Japanese army infantry

machine guns were encountered in fewer numbers.

5.

Mortars

Mortars were used extensively for harassing fire,

occasionally in conjunction with artillery fire. They were more effective

than artillery in producing casualties and delaying our forward elements.

Emplaced behind buildings, the mortars were difficult to locate. The

calibers most commonly encountered were 15cm, 90mm and 81mm. (Although a

new type of 81mm anti-aircraft mortar ammunition functioning as a

parachute bomb was found in Manila in 10 February, no reports were

received of its use).

On some occasions 50 mm grenade dischargers were

used by the enemy inside buildings for direct fire, and throughout the

city they were effectively employed against our troops in streets and

buildings.

6.

Artillery

In Manila, as elsewhere in the Pacific, the enemy

used his artillery as if for psychological effect rather than for

devastation. He seemed to choose as preferred targets our battalion,

regiment and division command posts, and placed accurate fire on them.

Other targets notably singled out were the areas of activity at the Allied

internee concentrations in Old Bilibid Prison and Santo Tomas University.

In addition, much harassing fire was delivered on our forward elements.

Occasionally a critical target such as a tank park was selected. In Manila

the enemy appears to have been too preoccupied with immediate targets to

attempt counterbattery fire. Pre-registered fires were frequently employed

to cover minefields, critical road junctions, and buildings most likely to

be used by our advancing forces.

On targets of all kinds, the enemy failed to mass

his fires for destructive effect. Except during a few periods at the

height of the battle for Manila, he directed the fire of only one to three

guns at a given target. In this way he drew our counterbattery fire on a

minimum of targets and conserved some of his pieces for later use.

The main artillery weapons used in the defense of the city were the

12cm Type 10 high angle gun (navy) ; the

8cm (3 inch), 10-year type high angle gun (navy) ; and the 75mm field

gun Model 38 on either a

wheeled carriage or a modified pedestal mount.

The 12cm high angle naval gun formed the backbone

of the Japanese artillery defense. Thirteen were captured or found

destroyed in firing position in Manila, and others located at Nichols

Field and Fort McKinley were actively employed. They were set on pedestal

mounts, permitting wide traverse. A few were emplaced for both

antiaircraft and ground fire. In the Laloma Cemetery a two-gun battery (a

third gun was on hand but not emplaced in its intended position) was sited

with an open view for AA fire and had wide horizontal views for

interdicting two main approaches to the city.

To compensate for the lack of natural concealment,

camouflage netting was used to mask each emplacement. These two guns also

covered a minefield lying south of Grace Park airfield. Near the Manila

Water Department reservoir two other 12cm guns were located; one of them

destroyed two of our medium tanks.

Time-fused incendiary shells were used to start

many of the city fires which destroyed blocks of buildings in the

immediate path of our advance. Air bursts about twenty feet above the

roofs discharged incendiary pellets into the buildings, while accompanying

high explosive air bursts discouraged immediate fire-extinguishing

operations. A normal proportion was two or three high explosive shells to

one incendiary.

Direct fire, principally of 47mm and 75mm guns,

was used from time to time both in street fighting and against buildings.

During the shelling of Santo Tomas University, direct fire against

buildings came from a 75mm gun or guns situated in an upper floor of an

enemy-held building. Authentication of such an emplacement is found in the

following translation of excerpts from a captured message book which

belonged to a Probationary Officer BATA (unit not stated):

10 Feb—At 3d Shipping Hq.

"0130—2d Lt AINOUCHI came from Detachment

Headquarters and requested me to emplace one field gun; we decided to put

the OP on top of the building and emplace the gun on the third floor.

0500—2d Lt AINOUCHI and artillery personnel came

from Detachment Headquarters and by using Chinese coolies carried the gun

up to the second floor. Later, the platoon leader and 6 men came to help

and, with their cooperation, we carried the gun up to the NE corner of the

third floor.

0830—Commenced firing. Target—Santo Tomas

University. Distance—3400 (TN: possibly meters). First round burst 5 mils

to the left of the building. Aimed to the right and fired two rounds. They

hit to the right and at the base of the building. White smoke is seen.

Thereafter we fired fifty to sixty rounds continuously; fell in the

vicinity of the target.

1000—Until 1000 the enemy did not fire. An enemy

plane is flying over and appears that it is making an observation of our

positions. About this time one enemy shell landed on the center of this

tower, and shrapnel fell. Approximately one minute thereafter two more

rounds landed. Our forces continued their fire.

Ten minutes after the first round, four rounds in

succession fell. Four more rounds followed and hit the pillar. One of

these fell in the vicinity of our position. Before the first enemy round

landed, I encouraged the gunners, asked them to oil the muzzle of the gun,

and went down to my quarters."

/4

|