|

Now came serious military training. The 26th (Yankee) Division traveled to

North Carolina for large-scale maneuvers. I remember little about them. As

an unofficial noncom I was responsible for getting kitchen trucks to the

right locations in time to feed the troops of the 181st Infantry. We spent

hours upon hours moving from one place to another, never knowing why or

where. During one day of idleness I was summoned to regimental

headquarters. It appeared that Massachusetts Governor Saltonstall was

visiting the regiment and had asked about me. By the time I got to

headquarters he had moved on. I guess he made the gesture as a favor to my

father, then the emergency commissioner of public welfare for the state.

In any event, this high-ranking interest in a lowly private did nothing to

ease my burdens or enhance my standing. I was still a truck driver.

Then the mock war ended and we began the long drive back to our base on

Cape Cod, arriving in early December.

Then it all got serious. On Sunday, December 7, some of us were sitting in

the barracks, talking and joking and cleaning our rifles. We had a radio.

We heard the voice of President Roosevelt. He said the Japanese bad

attacked Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands, "a day that shall live in

infamy." One of the guys put on his helmet, shouldered a rifle and marched

out the door, declaring death to the Japs.

It looked like we would be in the service of Uncle Sam for a long, long

time. A few weeks later I applied for admission to the army's Officer

Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia. My appearance before the

screening committee was uneventful except that I failed to identify the

squad as the basic infantry unit. They approved my candidacy anyway and in

early March I arrived at Fort Benning. There followed three months of

training, much of it similar to the basic training I had undergone as a

draftee. We did get more chances to fire on the rifle range and to

practice with bayonets and to improve our ability to read maps. Then, of

course, there was a lot of spit and polish and, believe it, instruction in

the giving of commands.

All through these three months we could see the tall steel towers in the

distance where would-be paratroopers took their training. A few of us

decided that was what we wanted, not just because of the presumed glory of

it, but also because of the extra $100 a month officers received for the

risk. So, about the time we graduated as second lieutenants, about 100 of

us lined up for interviews. Not all got accepted. I was mildly surprised

to be one of the 25-or-so lucky ones.

Officer school graduates were granted ten days leave before reporting to

their next duty station, I went home to Worcester to see my fiancée, a

girl named Mary Kneass. Way back when I was a lowly GI, I had proposed and

she had accepted. On a weekend visit from Camp Edwards I spoke to her

father -- in a sort of roundabout way asking for his permission to many

Mary. He called for his wife and called for a drink, so I knew it was OK.

Parachute school was rough. The curriculum, if one could call it that, was

divided into four one-week sessions. The first week consisted of mornings

spent in agonizing physical training and afternoons in learning to pack a

parachute. The second week was even worse, more of the same. I can

remember doing deep-knee bends until I fell on my face at the bottom of

each bend. This was the weeks were introduced to the plumber's nightmare,

a giant jungle gym on which were required to act like monkeys. We also did

some exercises in a gymnasium. One of the requirements for continuing was

to climb a 30-foot rope. I failed the first few times; got close, but ran

out of gas. Finally, on the last day, I made it to the top and hung there

until the achievement was recognized.

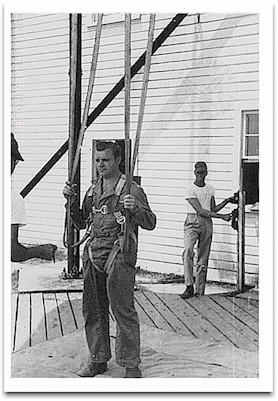

A minor torture was a suspended parachute harness. This consisted

primarily in repeated chin-ups while holding on to risers. The instructor

in this bit of self-torture was a beefy sergeant who could chin himself

while holding on to the straps with nothing but thumb and forefinger. And

then there was the 40-foot tower, a spindly structure with a hut-like box

at the top. You climbed a ladder to get there and were greeted by an

instructor who handed you a parachute harness and told you to stand in the

doorway cut into one side. A cable ran from the harness to another, long,

inclined cable outside. When you jumped out the door, you fell 15 feet or

so, were caught by the inclined cable and slid to the earth.

When we assembled around the base of this new test the instructor asked

for someone to volunteer to go first. No one spoke up. Since my name began

with A, I knew that with no volunteer I would be ordered to go. So, I

volunteered. When I stood in the door it looked like a long drop to the

ground. I was frightened, but when the instructor yelled "Go!" I went —

and there was nothing to it. Others followed, not all successfully. One

broke his arm when it was struck by a snapping-tight harness riser. An

instructor on the ground made notes on each jump. When all were through I

asked him how I did. He had made the notation "QF" by my name I

asked what it meant. "Quite frightened," he said. And he was right.

|