|

Several months later I ran into him again. We were on leave and had

traveled to the city of Townsville for what the army calls rest and

recreation. Again he was drunk and followed me into the restroom of our

hotel and once more offered to beat the shit out of me. But this time

and this situation were different. I ignored it and him and I never saw

him again. But I have always been grateful that he was not in my company

or my platoon. Fortunately, I never had any problems like that with my

own men.

Indeed sometimes they went out of their way to avoid trouble. On one

exercise we marched for hours in the hot Australian sun, loaded with

full equipment. One man, a short fellow named Tallent, was carrying, in

addition to his regular stuff, a mortar vest. This consisted of a piece

of canvas with a hole for the head and three deep pockets front and

back. Each pocket held a large cardboard tube containing a mortar shell.

Total weight, some 43 pounds.

As we pounded along through the dust and the heat I could see that

Tallent was struggling with his load and I became concerned. So I

offered to carry the mortar vest for a while. “Oh, no thanks,

lieutenant, I can handle it.” After several similar exchanges I gave up,

knowing that nothing less than a direct order would force him to

surrender the load. It wasn't until the next day that that I learned all

those cardboard tubes were empty -- no shells! No wonder he didn't want

to give me the vest.

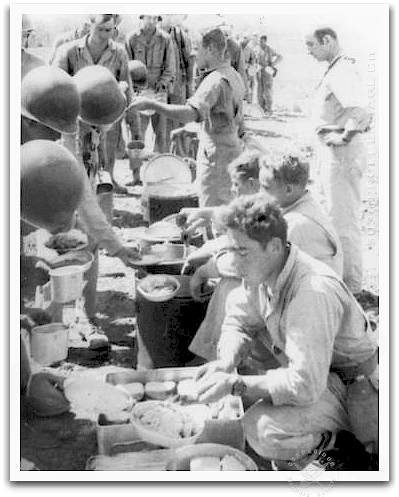

When did we finally leave Australia for New Guinea? I don't remember.

But I do remember that was the beginning of my greatest adventure in the

service. We set up camp near Port Moresby, then the only place in New

Guinea with any pretensions of civilization -- and not many of them I

think there was only one, permanent building in the place and that was

the governor's mansion. We lived in tents, of course, and carried on

with the same kinds of training we had in Australia, lots of tactical

exercises and climbs up nearby mountains and some live firing exercises.

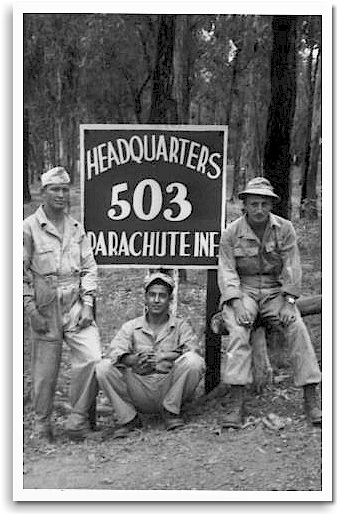

This went on until the day I was summoned to regimental headquarters.

There I was introduced to a very well set-up Australian lieutenant who

greeted me with the words, "So this is the body basher!" He knew more

than I about the purpose of the introduction. The field officer who

introduced us explained that the Aussie was an artillery man and I had

about two weeks to teach him and his 28-or-so soldiers how to jump out

of airplanes and figure out how to drop their two 25-pounder guns to the

ground.

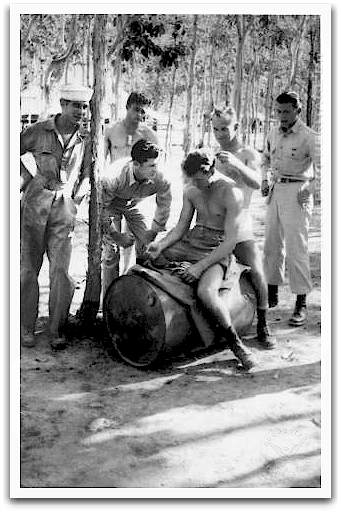

Every morning thereafter a truck delivered my Aussies to camp for

training. Fortunately, I had two excellent sergeants to help me. The

conditions were pretty primitive and so was the equipment. We built a

small platform under a tree and hung a parachute from a branch above.Of

course, we tortured our students with physical exercises and speed

marches, hoping primarily to build strength in the legs to withstand

landings. Then we hung them in the parachute harness and taught them how

to maneuver by pulling on the risers. Meanwhile, our riggers were

figuring out ways to bundle the cannon so they could be parachuted. The

Aussies were tough and willing and I soon became good friends with their

leader and his two or three fellow officers.

It seemed that we had hardly started the training when I was informed

that they were to make a practice jump. By this time they all knew how

to don a parachute and all were equipped with American steel helmets.

Australian helmets, with their sharp brims, were not suitable. They all

had made jumps off the low platform we had built and practiced limited

maneuvering while suspended in the harness. Ready or not, we had our

orders.

I'm sure they were scared, but all faced the jump with considerable

courage. We emplaned at a nearby field and took off. To my surprise we

were accompanied by a few high ranking officers, including a General

Vasey of the Australian army. It was apparent that higher ups in both

armies regarded this as an important experiment. Once over the

designated target, a cleared strip in the jungle, I stood my Aussies,

ordered them to hook up to the cable and stand in the door. Then the

command to “Go!” Every man flew out the door and all but one landed

safely. The exception was a lieutenant who broke his leg on landing. The

big guns were dropped from a following plane, but not with perfect

results. One was damaged enough so that it could not be moved around.

Nonetheless, the operation was a success. My orders were clear. When we

went into combat, it would be my job to get these men safely on the

ground.

Not long after the trial run we faced the reality of a mission. The

target was a place in the jungle called Nadzab. It was about 20 miles

inland of Lae, a major Japanese facility. September 5, 1943. Plane after

plane filled with paratroopers took off from airstrips near Moresby. In

one of those planes were my Aussie artillerymen, four officers and 28

men.

I learned later that Generals Kenney and MacArthur flew overhead in

B-17s to witness the operation, and the number of planes in the air set

a record. I was supposed to drop the Aussies about an hour after the

regiment landed, so my planes stopped for a while at a place called

Dobodura. I hadn't been told that was a scheduled part of the operation,

so I fussed and steamed until we were finally permitted to take off. |