|

We did not know where we were going, but we were certain it would not be

Europe. Instead of heading straight across the Pacific, we sailed to the

Panama Canal, where we were boarded by what was to be our second

battalion, some 600 men who had been training there in jungle warfare.

Then we sailed again, one small ship all alone in the vast Pacific. No

escort. The Poelau Laut was not a large ship and it was jammed to the

railings with the 503d Parachute Infantry. No room for training beyond

exercises and lectures. Each night the vessel would make a large circle

and one of the ship's officers would yell out over a loudspeaker, "You

can doomp the garbitch now." That left a huge circle of garbage behind

the vessel so no enemy ship could follow our trail through the waters.

One day when I had no duties I stood by a railing on an upper deck near

the ship's officers cabins. There I was joined by an elderly man who

introduced himself as M. Visser, chief engineer of the Poelau Laut. He

asked lots of questions about my background and then invited me to his

cabin where we continued our talk and a Javanese boy served me a glass

of beer. As the trip progressed I thanked God for Mr. Visser. He had a

sizable library of paperbacks and I could repair to his cabin whenever I

got another kind of cabin fever. By comparison to the crowded quarters

offered our officers his cabin was luxurious and, of course, way beyond

comparison with the holds where our troops slung their hammocks.

Weeks went by. Then one day we steamed into the harbor at Brisbane,

Australia, where we came closer to disaster than at any other time

during the crossing. Another ship suddenly moved to cross our bows. It

looked for a moment as a collision was inevitable. Bells rang, saxons

blew, men shouted. The two captains yelled imprecations at one another

like motorists. But we didn't hit and we dropped anchor in the middle of

the harbor.

The ship had barely stopped before a crowd of our men jumped over the

side and into the water, laughing and yelling and thrashing. No wonder.

There was no water aboard for showers. But the sailors were not amused.

They screamed at the men to come back aboard; there were sharks in those

waters!

As it turned out, Brisbane was not our destination. We upped anchor and

headed North, finally arriving at the town of Cairns in Queensland and

debarking there. There was a small delay, though. Australian dockworkers

were on strike and there were none available to unload our ship. No

problem. Among our troops were men who had operated cranes and done

construction work in civilian life. Soon enough all our equipment and

supplies were ashore.

The then little town of Gordonvale lies about 12 miles inland from

Cairns and just a couple of more miles more were open woods beside a

road. That was where we set up our base camp and where we spent some

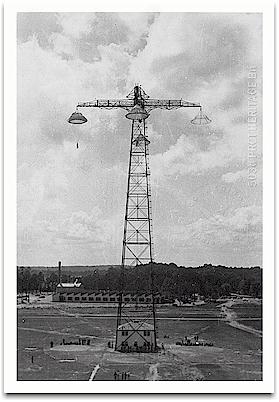

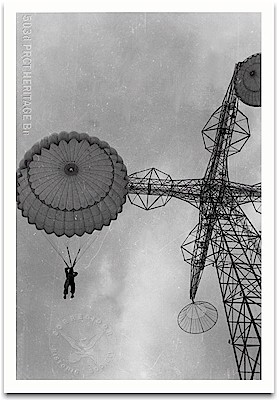

months in training for our eventual entry into combat. The training was

rough. We made grueling hikes through the mountainous country nearby. We

made parachute jumps. On one or two occasions we engaged in mock warfare

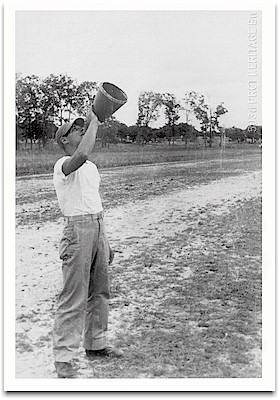

with Australian troops. This, too, was the place where I made my first

and only free jump. I was working with my platoon when I got a message

to report to headquarters. I had, it seemed, "volunteered" to join some

other officers in a free parachute jump. So, we boarded a plane at the

nearby strip and began circling over a field not far from the camp. One

by one we jumped and I noticed that one lieutenant told others to

precede him. Finally, only he and I were left. He told me to go and I

went, remembering that I had no static line to pull open my chute and

that I had to pull the rip cord handle. Since we had been flying at

around 3,000 feet I had plenty of time to enjoy the drop and managed to

land close to a small group of officers waiting below. It was fun, but I

wondered about the man who told others to go ahead. So far as I know he

never jumped and I still wonder what happened to him.

That was the only break in training I recall. On one exercise troops

were loaded into a single plane, flown up high near the tableland and

told to march back to camp. Because of a problem with the plane my

platoon and I were the last to fly. I did not even have a map, so we

just started hiking down the mountainside in the dark to where we

thought the rest of the troops would be. We were lucky. We found them,

sitting around a fire and roasting a pig they'd bought from some farmer.

On another day the whole regiment marched from camp up into the nearby

mountains. Hours went by and the miles fell slowly behind us. Once, when

we had stopped for a short break, the colonel walked by us on the narrow

trail and asked, " How are you doing, Armstrong?" "Fine, sir," I said,

although my feet were swollen and sore, but what else could I say? Not

so diplomatic was one of my men. "Fuck you, colonel," he said,

fortunately not loud enough for the colonel to hear. He knew, as we all

did, that the colonel had not accompanied us on the march. He'd ridden

in a jeep.

When dawn broke the next day my feet were so swollen I doubted I would

be able to walk. Fortunately, we were met by trucks and carried back to

camp. Three days of that mountain hiking and stream crossing was enough.

Back to small unit exercises. I had taken my platoon away from camp and

up on the side of a small mountain , where we set up the mortars and

practiced firing -- with no ammunition -- at some other mountains far

away. In order to get better vision on the target, I climbed a tree...

Disaster. The branch I stood on broke off and I fell, impaling a thigh

on another stub as I dropped. Someone got an ambulance; I don't know

how, and I was carried to the little aid station in Gordonvale, where I

spent three or four days recovering from my first "wound." One day a few

of my men visited me in the hospital and I have never felt so honored.

Some two thousand American soldiers encamped just a couple of miles away

could be a problem for the little town of Gordonvale. So our leaders set

up a protection program called an interior guard. We erected a tent on

the little common in the center of town and our units took turns

operating what was, in effect, a military police station. Our turn came

and my platoon and I took up temporary station in the town. My men

walked patrols in the evening to make sure nothing happened. But

something did. A soldier from another company was picked up for throwing

rocks at streetlights (and Gordonvale didn't have many of those,) being

drunk and disorderly, out of camp without a pass, and out of uniform.

Two of my men brought him to me in the guard tent. He was obviously very

drunk and very combative. Before I could say very much he began

insulting me and yelling to all my men that he was going to beat the

shit out of me. Up until that point I could have had him escorted back

to camp and turned over to his own officers for company punishment. But

not now. If he got away with that behavior, what effect would that have

on the discipline of my own men? So, guards took him back to camp and

turned him in at the stockade, a kind of regimental jail. A few days

later I preferred charges and he was sentenced to six months in the

stockade and the loss of two-thirds of his pay. |