|

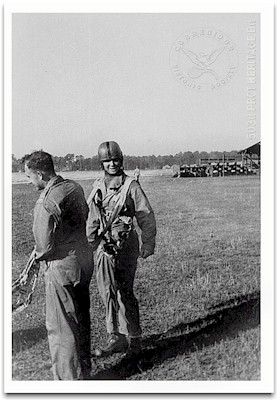

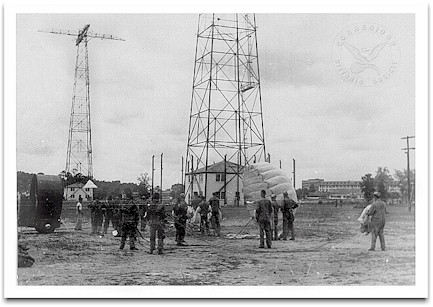

Was it the third week

when things got a bit easier? This was when we were introduced to the

steel jump towers. Actually, they were fun.

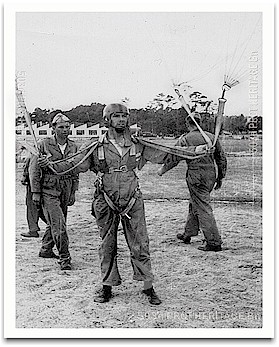

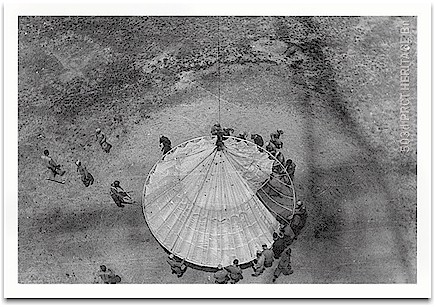

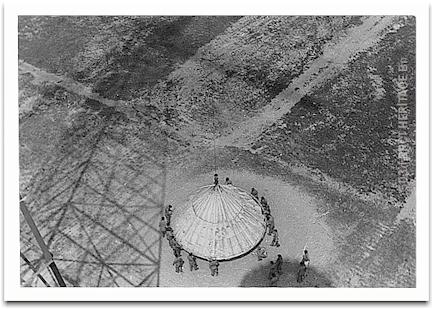

Parachutes were held

open by clips attached to wires running from

earth to the top of the tower. You stood under the chute in your harness and

were hauled 200 feet into the air. At the top the chute was released and you

floated back to earth, guided by the vertical wires. That was the easy part.

The tough part was what I called the no-chute test. You lay on your belly on

the ground in your parachute harness. The harness was attached to a cable at

your back. There was no chute. At a signal you were pulled 150-feet into the

air, still horizontal. There you hung until an instructor with a megaphone

yelled up, "Pull!" At which command you pulled the rip cord at your chest

and you began to fall. The harness tightened after 15 feet and you were once

again vertical, jerking up and down like a rag doll. Then you were lowered

to the ground and another student took your place. The purpose of all this

testing of body and mind, I later realized, was to weed out those of us who

would not or could not endure it.

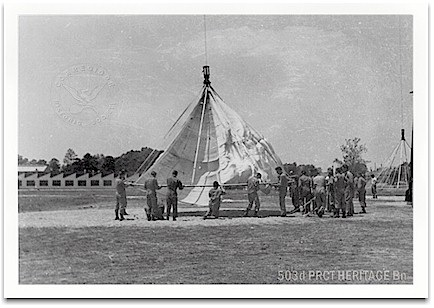

The fourth and final week was the easiest of all. All you had to do was make

five parachute jumps from a couple of thousand feet from a plane flying over

a field. If you balked or got badly hurt you were out. By this time some of

us had already been dismissed. You jumped one at a time, a tough sergeant

standing behind you to make sure you went out the door as ordered. You

didn't have to do anything, just jump. A 40-foot static line running from a

wire in the plane to the back of your harness pulled out the chute from its

pack as it broke away. But it was both fun and exciting and at the end you

got your wings and were a qualified paratrooper, ready for assignment to a

fighting unit.

I don't know where most of my fellow graduates went, but Guy Campbell and I

were sent to the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment at Fort Bragg, North

Carolina. We were ordered to report to the commander of Headquarters Co.,

Battalion, for assignment. After a few questions the captain realized we had

practically no experience in combat units. He assigned Guy to the light

machine gun platoon and me to the 81mm mortar platoon. Because the army

expected a high casualty rate for paratroopers, each platoon had two

officers. My leader was a Lieutenant Fickle (Fickel?), a man I soon came to

like and respect.

A mortar is a cumbersome weapon, consisting of a steel tube through which to

fire the shells, a bipod to support the top end and hold the sighting

mechanism, and a heavy steel base plate to hold the bottom of the tube. Each

part is heavy and awkward to carry, the base plate especially. We learned

that the hard way, because we carried our four mortars with us on every

march and tactical exercise.

I grew fond of those mortars. Awkward and heavy they might be, but they

could throw a seven pound shell almost 3,000 yards, flying high over any

obstacles and exploding effectively on impact. They were simple to use and

had no moving parts to break down. All you had to do was set the sight for

distance and aim and drop a shell down the tube. Then you made adjustments

to cover your target. That's an oversimplification, of course, but it's

basically what we did.

When we went on a tactical exercise, the mortars were disassembled and

rolled into heavy fabric bundles, along with the ammunition. Each bundle had

its own parachute. In flight we stacked two bundles in the open doors of

each of our planes, pushed them out at the drop point and jumped after them.

That was the fun part. Most training hours were spent in marches, dry firing

exercises, platoon tactics, and the like. One day the whole first battalion

stripped to shorts and shoes, ran two miles to a lake for a brief swim, and

ran back to barracks.

This went on week after week. And then we began to wonder how long it would

last and when we would be shipped out to a theater of war. With that came

the realization that I might lose my intended if I was gone for long. So, I

wrote to Mary and asked her to come down to Fayetteville and marry me. She

must have had similar fears, because she wrote with the same idea and our

letters crossed in the mail. I managed to rent the ground floor of a small

house in the town and arranged for the wedding to be held in the Episcopal

Church on August 8, 1942. Meanwhile, I visited regimental headquarters,

talked my way by a stuffy staff officer, and invited the colonel to attend.

I also invited a few of my buddies. Both sets of parents, plus my two

brothers, arrived in time to witness the ceremony. That was followed by a

small, very brief party. And we were married. The following morning I

hoisted Mary over my shoulder and went out on the front porch to greet our

families. Just hours later, they were gone, on their way back to

Massachusetts, and married life began. Mary couldn't cook very well, but we

had a lot of Charlotte Russe, which she could cook. And once in a while, we

would be joined for dinner by a friend from the regiment. Meanwhile, our

training went on. But not for long. Somewhere near the middle of October we

got orders to ship out and the regiment assembled at the nearby railroad

track, where we said goodbye to friends and family, and boarded the train

for a long, long trip to San Francisco.

Most thought we would end up in Europe. If not, why did they issue us long

underwear? The train was slow and all window shades had to be pulled. It was

boring, boring, but I did learn to play redeye and lost a few dollars in the

process. In about seven days we arrived in San Francisco and were taken to a

nearby camp. I don't remember how long we were there, perhaps a night or

two, and then were driven to the harbor, where we boarded a Dutch freighter,

the Poelau Laut, which would be our home for the next 44 days. |