|

trail and asked

how he was, he said "Mediocre, lieutenant." A little later we wrapped him in a

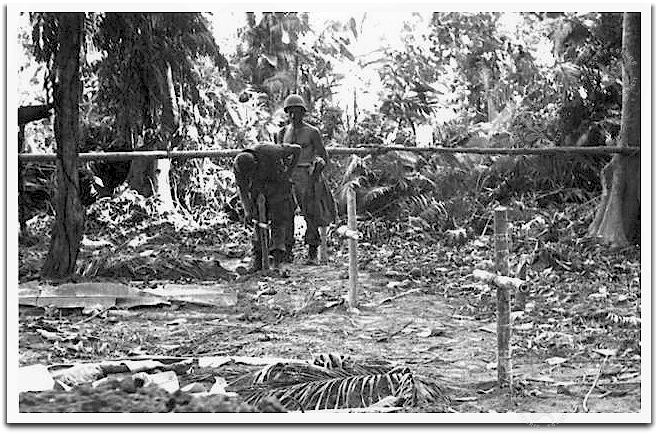

poncho and buried him and the corporal who had died in a shallow grave. Sergeant

Lassiter, the one wounded man, was placed on a crude stretcher and we carried

him back to the shore and medical attention. I never saw him again.

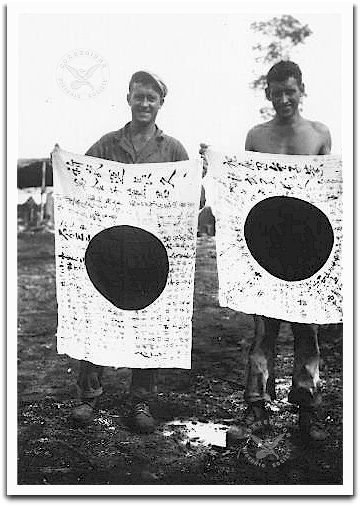

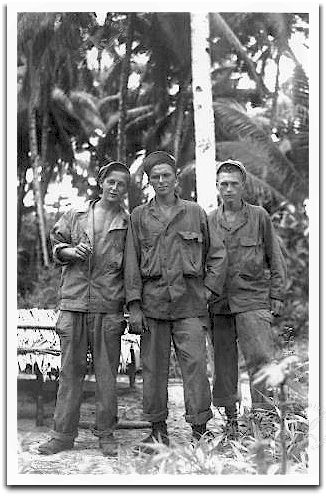

That was our fist real firefight. Later, the 503d moved deeper up the coast of

Noemfoor, engaging in small actions along the way as we sought to eliminate

Japanese resistance. I had been sick again when I rejoined the outfit at some

unnamed place on the shore. Half of my platoon had moved further up the coast in

support of infantry action and I was told to join them. Unhappily, I was not in

time to go in a small landing craft and started hiking the few miles between the

two positions. With me were two men of my platoon, both good soldiers. The trail

we followed was on top of a ridge lying above surrounding jungle. At one point I

called for a short break -- more stomach problems. But at the same time I

thought I saw movement in a small clump of grass at the edge of the trail where

the ridge descended into heavy growth below, and decided to investigate. Big

mistake.

Instead of taking my guys with me I told them to stay put and I would check it

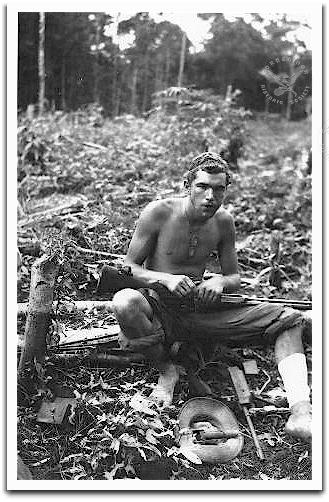

out. I moved slowly and with caution down into the forest, carbine ready. I

didn't have to go far. Just as I bent over, searching the ground ahead, I was

hit in the chest. It felt like I had been punched with a red hot iron. But it

didn't knock me down and simultaneous with the blow I saw an enemy soldier lying

down perhaps a hundred feet further down the slope. Firing from the hip I

squeezed off four or five shots and then, the hardest thing in my life, I

managed to get my weapon up to my shoulder and gave him three or four aimed

rounds.

That was it for me. I yelled for my guys, but I could no longer stand and sank

to the ground. Moving cautiously, they checked to make sure my Jap was dead and

finally reached me. By this time I was in great pain. Fortunately, we carried

individual morphine shots with us and a needle in my arm brought some peace. In

truth, it brought moments of unconsciousness.

Later, borne on a stretcher, I finished the trip to rejoin half of my platoon

and was loaded on a landing craft for the trip around the island to a field

hospital. I remember little of that brief voyage except that I was very thirsty

most of the time when I was conscious. When I awoke at the hospital, just a

collection of tents and cots, I was on an operating table, where I greeted the

surgeon and passed out again. The bullet had passed all the way through my body,

entering just to the left of my heart, nicking a lung and exiting through a

scapula in my back. When I got a bit better they sat me on the edge of my cot

and the doctor inserted a long needle in my back and pumped fluid out of a lung.

The procedure was repeated later after I had been transferred to a more

permanent hospital somewhere else, but this time in a well-equipped operating

room.

Eventually I recovered enough to walk a little and I boarded a hospital ship for

the return to the States. It took a lot less time to return than it did to sail

over -- something like ten days as compared to 43. Then followed a train trip to

Washington and another hospital, this one Walter Reed. Prior to arrival I had

sent telegrams to Mary at every stop, telling her present location and reporting

progress. She had found a room at the Willard Hotel and, somewhat to my

surprise, hospital authorities said I could go there to meet her. The Willard is

a large old hotel, one with long corridors on each floor. I walked down one of

these until I came to her room. I stared for a moment at the number on the door,

then walked back to the elevator. Not hesitant, not uncertain. I just wanted to

savor every second of our reunion. And when I knocked and she came to the door

and I held her in my arms for the first time in more than two years, it was all

worthwhile . I was home.

But all was not perfect. Not for me, at least. The hospital let me travel to

Massachusetts for a few days with Mary's family. I was not cured. Once again I

suffered from a bladder infection and had to return to Walter Reed in some pain.

Eventually, after days of misery in bed, I was given spinal anesthesia and a

doctor introduced silver nitrate to my bladder. Once the anesthesia wore off I

was again in agony. But it didn't last forever and the army sent me to the Grove

Park Inn in North Carolina for ten or so days of rest and recreation. Then we

went to another recuperation facility on Long Island.

I was finally returned to duty at Fort Bolting. That did not last long. Came a

telegram from Washington ordering my presence at the War Office. There I got my

orders; Go to Camp Campbell, Ky., with a few enlisted men with some

communications experience and make the surrounding towns and cities offer a

hearty welcome to the members of the 5th Division who were returning from

Europe. This was the best duty ever. Mary and I lived in quarters for visiting

officers and were served great meals at a mess operated by Italian prisoners of

war. Once a month I reported progress to my boss in Washington. No one bothered

me. My crew and I had little difficulty persuading people to make the troops of

the 5th Division feel welcome. Of course it was too good to last.

In a phone conversation my boss said he wanted me to go to California to do a

similar job for a corps returning from Europe. Uh uh. I wanted out. There soon

would be thousands upon thousands of discharged soldiers and sailors who would

be looking for jobs. I wanted an early start. By the then-used point system I

had enough credits to get a discharge from the army. I got it. So I took my

Purple Heart and brand new captain's bars and said goodbye to military service.

After some five years in uniform I was a civilian once more. And damn happy to

be there.

Robert W. Armstrong

|