|

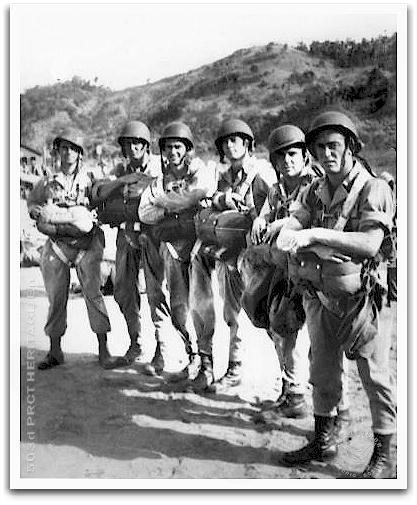

We arrived at the drop zone, a huge field of grass, and our pilots dropped down

to somewhere between 400 and 600 feet. I had no exact idea of our destination,

but as we neared the end of the field and the green light was on, I gave the

command to go. Nothing to it. Every man leaped from the plane and the

25-pounders were dropped from the following C-47. I did not jump -- not then. I

had chores, consisting of circling around the field and throwing out equipment

needed by our troopers and Australian engineering troops below. The engineers

had marched overland to the site and it would be their job to restore the

long-abandoned airstrip in the field so Australian infantry could be flown in.

When I finally jumped, as close to my artillerymen as I could, I found myself in

a sea of kunai grass, sharp-edged grass six or seven feet high. Or maybe more. I

found that I could get through it only by falling forward and pressing it down

with my body.

Eventually I reached my Aussies, happily sitting around in the shade of jungle

trees at the end of the field, their cannon already recovered. How they managed

that I never found out. I had received no orders to rejoin my own company, so I

spend the next 11 days or so loafing around with the artillery. Actually, we had

nothing to do. There were no Japs in the area; hence, no fighting. Some units of

the 503d did run into firefights, but nowhere near our location. The only injury

received by the Aussies was a skinned nose. A last-minute replacement for the

officer who had broken his leg in the practice jump had been equipped with an

ill-fitting American helmet which tilted forward with the opening shock and

peeled a bit of skin off his nose.

With nothing to do, I became impatient and one day walked off alone down a trail

toward the coast, passing one of our outlying guard posts on the way. After a

mile or two I became uncertain of my safety and turned back. Within moments I

heard the roar of engines and an American bomber passed close over my head,

raining down 50-caliber cartridge casings from its guns as it swept the area

with fire. It took a moment to realize that those were casings and not bullets

and I was not a target.

For me the operation was over. I read later that more planes were in the air the

day of our jump than ever before. We were very well protected. And I was never

in any serious danger. Two books published after the war briefly covered my own

part in the operation, not because of the danger, but because this was the first

time any Australians made a combat parachute jump.( The books were Paratrooper,

by Gerard M. Devlin, St. Martin's Press, 1979, pages 260 and 264, and Geronimo,

by William B. Breuer, St. Martin's Press, 1989, page 104.)

It was time to leave. Planes loaded with paratroopers were taking off from the

newly restored strip. John, my Aussie friend, had found a motorcycle somewhere

and drove me to the strip. I was in greater danger then than at any time during

the mission, bouncing around on the rear fender as we careened over potholes and

ruts, my rifle and equipment flying wildly in the air. I think that was one of

the last planes to leave. My Aussies rejoined their 7th Australian Division and

proceeded up the coast; I was sorry to leave them; they were a great bunch of

men.

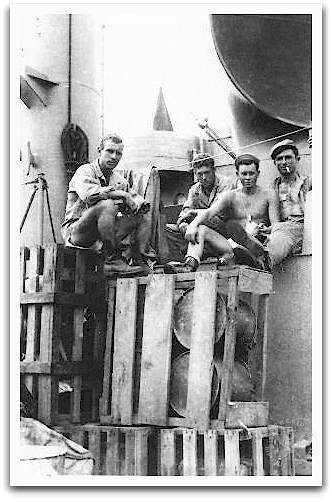

Back at our base camp in Australia things went on much as before. Those of us

who had joined the outfit back in America found ourselves promoted to first

lieutenant. Many went on leave and I was able to make a brief visit to Sydney,

the nation's biggest city. I regret to say that I did not frequent any museums

or other cultural attractions, but I did get to know some of the better watering

holes. Meanwhile, we learned that our commanding officer, Colonel Kinsler,

committed suicide. The regiment had been visited by the Inspector General and he

received many complaints about the outfit. Perhaps the colonel received serious

criticism about some aspect or aspects of his performance as commanding officer.

We never knew.

Before we left for our second visit to New Guinea, I got sick with a very

painful bladder infection. It got worse and by the time we reached the island I

had to go to a hospital, where I spent a few weeks of mainly ineffective

treatment. But I did begin to improve

and eventually rejoined the outfit, which by this time was engaging in clean-up

actions along the coast. I was still sickly and did not participate. improve

and eventually rejoined the outfit, which by this time was engaging in clean-up

actions along the coast. I was still sickly and did not participate.

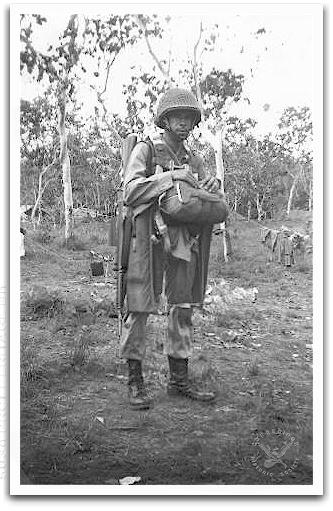

Within a few weeks it was time to go back to work. Our mission this time was to

jump on a sandy airstrip on the coast of an island named Noemfoor. Our job:

reinforce an infantry outfit already in place and bogged down by Japanese

resistance. This jump was not as easy as the one at Nadzab. Our train of planes

circled in from the sea and flew down beach. But they flew too low and many were

the injuries and broken legs from rough landings. Many jumped as low as 200 feet

and their chutes did not have time to open properly. But we still had a job to

do and we began it with a series of patrols and probes into the surrounding

jungle. This was the first time that many us actually faced enemy fire. My

mortars were not of much use; we had no visibility at all on possible targets.

Nonetheless, we were ready. |